Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

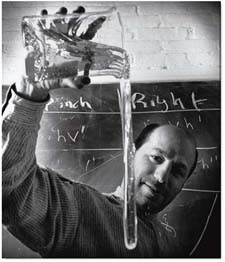

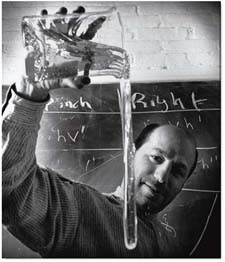

Photograph by Flint Born

|

In the beaker is a syrupy liquid, glycerin, to which Howard Stone has added

a small amount of a soluble material with very long molecules, polymers.

At rest, the polymers want to position themselves like a ball of string.

When the liquid is poured, the string stretches out, but says to itself,

says Stone, I want to be coiled up. With the least encouragement, a twitch

of the hand, the liquid springs back into the beaker. Stone is a recently

tenured professor of chemical engineering and applied mechanics. When he

came to Harvard seven years ago, after a postdoctoral year at Cambridge

University, his research interest was the behavior of small particles in

fluid. While Cambridge University teemed with people in his field,

Harvard had no one. "I almost require other people to talk with in

order to exist," says Stone. Since the behavior of fluids is important

to scholars in many fields, Stone found intellectual colleagues outside

his discipline. He has done much collaborative work-in earth sciences, for

instance, where fluid mechanics can help explain motion in the earth's

mantle. Stone is a superb teacher and has won both the Joseph R. Levenson

Memorial Award and the Phi Beta Kappa Undergraduate Teaching Prize. When

he isn't collaborating or teaching, he's apt to be playing basketball, which

involves the movement of an object (the ball) through a fluid (air).

Both liquids and gases are fluids because if you push on them, they

move. That's lesson number one.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

![]()

![]()