Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

| Tiny Music Critics | Bibliocide |

| Literary Tigers | Frozen Brains |

| Lynching as Human Sacrifice | E-mail and Web Information |

|

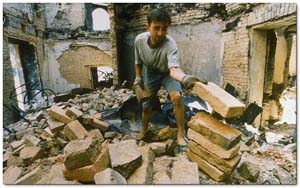

| Photograph courtesy of Reuters/Corbis-Bettmann |