Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

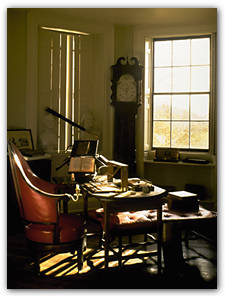

Jefferson's political reputation may rise and fall, but this chair with leg-rest in his study at Monticello secures his fame as seating innovator.R. Lautman / Monticello |

Why is it so surprising that chairs should be valued for their external meanings just as neckties and high heels continue to be, despite a century of clothing-reform movements? The necktie is not based on ignorance of air circulation, nor the dress shoe of podiatric health; instead, each expresses image and convention. Modernist furniture expresses a certain this-worldly asceticism that Max Weber ascribed to Protestantism, and a certain denial of comfort may even reinforce the idea of fitness to rule. According to the writer Philip Weiss, Spiro Agnew avoided leaning back in his chair to prevent creases in his suits. This consciousness of image he shared with his late-modernist foes. Indeed, as the architectural historian Joseph Rykwert observed, the very discomfort of the celebrated Hardoy (butterfly) Chair was a sacrifice the owners gladly made to underscore the antiauthoritarianism that its unstructured suspension system betokened. The chair allowed a new elite to display its superiority to tufted, overstuffed fogies, just as Agnew's immaculately pressed look confounded the rumpled and pointy-headed.

Of course this suffering to be beautiful or powerful or progressive has a sinister side. It is only a short step from the chair as self-discipline to the chair as control and correction. It is interesting that a popular Chinese adaptation of European chair design, imported into Europe in the eighteenth century, had its back in the form of a yoke. A chair is a kind of social yoke. Those who saw the play or film of Alan Bennett's The Madness of King George will recall the sinister debut of the Reverend Dr. Thomas Willis's specially built chair, in which the erratic king was clamped by Willis's strong-arm attendants when he resisted the doctor's regimen. In real life the king sardonically but tellingly called it his Coronation Chair, and it differed from the wooden armchairs of the day mainly in having a large, flat base that effectively anchored it to the floor. Not many years thereafter Dr. Benjamin Rush, the Philadelphia patriot-physician, introduced a similar chair for the insane, augmented by a hood. Much later, interwar Scandinavian functionalism could also be an almost sinister source of control; Grimsrud said of the Finnish architect Alvor Aalto's "sanatorium chair" that "[i]f the patients were not already sick, then they certainly would be" after sitting in one of them. Even today, high-tech "violent prisoner restraining chairs," with due precautions against "positional asphyxia," appear at corrections trade shows.

A century after George III's treatment, New York State introduced the ultimate extension of Dr. Willis's

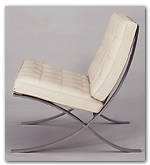

Harvard's presidential seat and Mies van der Rohe's Barcelona Chair are made of sterner stuff.Top, Michael Nedzweki / Harvard University Art Museums; Bottom, The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Is there a natural way to sit that avoids these alarming precedents? Most of the world's peoples sat at mat or carpet level before contact with Mediterranean chair sitters. There are reasons to believe their body techniques (in Marcel Mauss's phrase) may be healthier than those of chair sitters. A Sudanese professor of medicine compared the eating and defecating patterns of nomads with those of medical students in Khartoum and concluded that squatting, along with bulkier food, reduced the rate of hemorrhoids and varicose veins among the former. Some physical therapists have observed fewer complications in childbirth among women who have grown up in non-chair societies. (But then again, squatting and kneeling may have pathologies of their own. The skeletons of some peoples reveal depressions in certain bones of women from prolonged kneeling in food preparation; one official of the Japanese health ministry believes that chair sitting as well as improved nutrition has made the postwar generation significantly taller than its parents.)

For better or worse, chairs have moved around the earth as though they had walked on their own legs, spread not only by the Spanish friars we have noted, but (for example) by medieval Nestorian missionaries in China, by early modern Portuguese traders in West Africa, and by French and other diplomats in the Ottoman Empire. The famous Golden Stool of the Ashanti, the embodiment of nationhood, was even enthroned on a chair of its own. Chairs carry us, and we carry chairs.

At first the chair coexists with ground-level customs. For years, many Japanese households maintained both tatami and Western rooms, with different proportions and décor as well as different seating. But this seating truce has proved unstable. In Japan at least, younger people report increasing discomfort in the floor-seated positions as they practice them less, a self-reinforcing cycle. Both Western reporters and at least one Japanese colleague note the decline of traditional seating. The kneeling position of seiza, familiar in Zen meditation and in school discipline, has become harder for the Japanese to sustain for any length of time. Nonwesterners have shifted to chair sitting not because it is a form of comfort they had been too hidebound to invent--the Japanese used chairs for centuries in a number of settings--but because of the chair's way of re-forming the physical as well as the social self. We make chairs and chairs make us.

We are still not quite happy with our chairs. Chairs for conversation and rest reached a high level more than 200 years ago, and the sprung furniture of the nineteenth century may even have been a step backward. The quest for too much ease began to threaten well-being. As the designer Karl Lagerfeld put it, "It has been said that conversation died in France when chairs became too comfortable." The "elaborate padding of nineteenth-century upholsterers" made wit itself ponderous, whereas "in a bergre the mind can remain lively and alert."

Neither authority, nor conversation, nor wit is the object of today's chair; it is the manipulation of symbols on cathode ray tubes. And here the genius of the Rococo as celebrated by critics like Rybczynski is of little help. The computer has had some terrible unintended consequences in helping to multiply the reported rates of cumulative trauma disorders, but at Harvard and elsewhere these problems have also had a positive effect. They have accelerated serious thinking and research about seating.