Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

In the nineteenth century, new quantities of padding and ingenious arrangements of springs attempted with varying success to assure new levels of comfort--a challenging enterprise considering the reinforced corsets of women and the

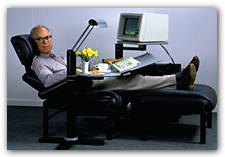

Nils Diffrient in his Jefferson Chair, at $6,500 the ultimate power seating of the dawning microcomputer age of the 1980s, and still in production. John Dommins / Courtesy Nils Diffrient |

The paradox of the twentieth-century search for the healthy seat is that it probably began not with ruling adult males but with the perceived needs of schoolchildren and mass-transit users. The first studies of proper seating I have found are treatises from the middle to late nineteenth century on the proper desks and chairs for elementary-school classrooms. Transportation companies followed only a century later; the Harvard anthropologist Earnest Hooton conducted an extensive physical measurement program for the New Haven Railroad in the 1940s.

While today's commercial airlines seem to get their seating ideas from M.B.A.s rather than either M.F.A.s or Ph.D.s, Rab Cross '67, M.D., an occupational medicine specialist and certified professional ergonomist, believes that military studies of pilot seating were the first scientific treatments of the needs of machine operators as opposed to passengers or pupils. My own search of the papers of the pioneering industrial engineer Frank Gilbreth, at the National Museum of American History, reveals no attention to chair design, save an interesting concave footrest. Early textbooks of office practice are silent on such major topics as support for the lower back.

According to Cross, it was the computer that provoked the first extensive research and thinking about healthy seating in the office. Computers raised new questions about the proper height of seating in relation to work surface, about the optimum position of the body, and above all about activity. The physical dangers of the computer were unprecedented. With the computerization of the workplace, the old-style catastrophic industrial injury caused by a single traumatic event began to yield to a new and more insidious form of disability caused by the rapidly repeated performance of small motions

The Great Chair, seat of patriarchy, is ergonomic enough for hard-copy output. FPG International |

Today's ergonomic chairs are, from one point of view, worlds away from their origin in ceremonial role and constraint. Long vanished is the attempt to enforce a single optimum position. The chair is not so much a fixed object as a set of carefully formed and adjustable parts. A swiveling seat in Jefferson's day was a novelty. Even in the early nineteenth century, tilting chairs (like rockers) were domestic amenities, not commercial equipment. Now office chairs afford not only changes of seat height and back reclining angle--often with back- and seat-changing positions at carefully adjusted angles--but other degrees of freedom. The seat pan can tilt forward, as some ergonomists recommend for certain work. The position of the lumbar support, the height of and distance between the arms, the tension of the backrest, and sometimes the depth of the seatpan are all adjustable. A few chairs have split backs. Others, like the Equa II and the sculptural new Aeron, both lines designed by Bill Stumpf and Harry Chadwick for Herman Miller, are sized by body dimensions (small, average, and large) rather than by hierarchic and gender distinctions (secretarial, managerial, executive). The Steelcase Sensor, a favorite chair at Harvard, has "highback" and "midback" styles. New flexible synthetics are taking some of the role of springs and padding.

Yet for all these innovations, the chair is still the object of unease. Some models, based on slim European bodies, lose their lumbar support when larger American bottoms push sitters up and away. The more adjustments and possible seating positions, the more time the sitter has to take to learn them. Some employees never do. And some designers have even concluded that chairs should not be contoured at all, that they should be designed to encourage constant shifting. The Rudd International Cyborg of the 1980s had a weight-activated hydraulic cylinder. As the Rudd brochure explained, "the chair itself moves, making the user move--virtually all of the time he or she is sitting in one," yet slowly enough that "[m]ost people will find it impossible even to detect." (The maker, now Rudd Incorporated, offers a lower-priced successor called the Cyncro.)

The horizon of chair design seems to be the horizontal, with ever bolder reclining angles. Theoretically, if the body does not slip, a wider angle means

The "secretarial" chair was once openly marketed as a woman's chair, unlike the "managerial" and "executive" models that were always shown with comfortably sprawling males. Today's "assistant" has a "task" chair, still often smaller, with low back and no arms. FPG International |

Paradoxically, it is the very group that inspired some of the first anatomical studies of seating--students--who are now most at risk. Rab Cross's slides of Harvard students at work, taken with a House Master's permission, show (among other ergonomic problems) chairs utterly unsuited for computing. Cross, who with William A. Schaffer has published a book on personal workplace health called ErgoWise, warns that the true cost of universities' apparent indifference may appear only later, in workers' compensation costs to the graduates' ultimate employers. (Back pain is said to cost American business $6.5 billion annually.) Will Harvard, and students' parents, face yet another major investment? The chair, apparently so natural, turns out to be one of our most complex and least understood technologies, and in one way or another one of the costliest.

Contributing editor Edward Tenner, JF '72, is a visiting researcher in the geosciences department of Princeton University and author of Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences (Knopf). He thanks the Woodrow Wilson Center for Scholars for supporting the project of which this essay is a part.