Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

| Managing Your Money | Lala Rokh |

| Tastes of the Town | The Harvard Scene |

| The Sports Scene | |

Also see Assessing Your Assets

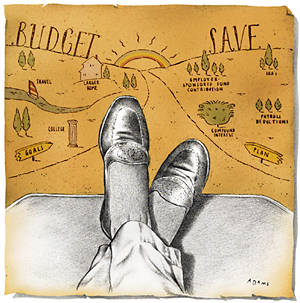

Illustration by Lisa Adams |

Yes, according to financial planners at Harvard University. "It's never too late," says Linda Willson, senior financial planning consultant in the Harvard Retirement Programs Office (RPO). "The best time to invest was probably 10 years ago. The next best time is today." The power of compounding means that your money will add up faster if you start earlier in your life--requiring you to save less each month to realize your goal, or enabling you to save more. Five years of funding a retirement plan (or a plan for any other financial objective) begun at age 30 has the equivalent effect on retirement income as 20 years of investing begun at age 45. But whenever you begin--at age 30 or 40 or 50--the rules of compounding do not change.

Willson and others in the RPO steer faculty and staff members through the maze of financial decisions and options facing those who seek personal and family financial security now and in the future. But the Harvard planners' techniques and tips can help anyone seeking greater control over his or her financial life.

![]()

The Harvard counselors begin by using a questionnaire to gather basic information on household income, assets, debts, and budget. Through referrals to outside financial-planning professionals, they can then help participants formulate a comprehensive, lifetime financial plan.

In the initial information-gathering stage, participants find that figuring out how much they spend each month is the worst part of the process. "Most people don't want to open their checkbooks and look," says Gary Pomerantz, an RPO financial planning consultant. "But it's one of the best things you can do."

A surprising number of people discover they can save $1,000 to $2,000 a year simply by cutting back on convenience spending--such as buying coffee on the way to work or going out for lunch every day. Those who use ATMs a lot and have no idea where that $100 goes every week, might do well to write checks or use a credit card--and pay their bills off immediately--to get a better sense of where they are spending their money, Willson says. Once you have a budget, you can see where you might be able to cut expenses, like going out to dinner one night a week instead of two or three. That can be the foundation of a savings program.

And the discipline applies later in life, too, Pomerantz says. Many people come into the RPO only when they are about to retire, inquiring about how much they will receive every year from pensions and savings--say $60,000--and thinking that they have all that to spend. But Pomerantz says it is far better to figure out how much of that money is needed for current expenses--perhaps $45,000 a year--and then invest the rest. Given today's long life expectancies, this can be an important source of funds for the future.

The next important step is figuring out your top three to five financial goals: to pay for your children's college education, perhaps, or to buy a larger house, travel, or retire at age 68 while maintaining your current lifestyle.

Knowing your financial status and goals, financial planners can then use information on inflation, typical rates of return on investments, and other data to project what you have to do to turn your dreams into reality. To illustrate this process, the Harvard planners and consultants have drawn up three hypothetical cases demonstrating how fictitious professors could meet their financial goals.

Underlying all the plans, however, is the unwavering advice that you have to save; that compounding investments over time is your most powerful tool; and that everyone should use certain savings plans. What's the best way to begin saving? The experts agree: an automatic deduction program that puts the money away so you never see--or miss--it. Maximize your contributions to employer-sponsored 401(k) or 403(b) plans, or to IRAs; qualifying contributions are excluded from current taxable income, and investment earnings in such plans compound on a tax-deferred basis as well. That lets you build up savings quickly, and then plan on using the funds in retirement, when your income, and tax rate, will presumably be lower.

![]()

Professor Brown, age 42, just received tenure. Her husband is also 42, and they have two children, ages 10 and 7. She expects a long career, with retirement at age 70. She earns $70,000 a year, and her photographer husband earns $35,000. Brown's objectives are to provide for her family in case of her death or disability, to fund the children's college education, to maintain financial independence in retirement and her current lifestyle, and to pass on any residual wealth to the children.

One of her first needs--commonly overlooked--is to purchase disability insurance. "Disability insurance is very cheap and it replaces about 65 to 70 percent of your income," Pomerantz says. "It is much more likely that you will be disabled than that you will die, so if you think life insurance is important, disability insurance is even more so."

As the second element in providing for her family, Brown should get rid of her whole life insurance and buy an adequate amount of term insurance. The planners' calculations reveal that she would need $350,000 worth of coverage to pay college tuitions and replace her income in case of her death. But whole life policies, which include a relatively meager investment return on relatively large premiums, are expensive. By switching to term, Brown could use the $1,800 she saves in annual premiums to invest in stocks or mutual funds that offer higher rates of return.

She is not contributing to Harvard's employee tax-deferred annuity, which provides a stream of monthly payments or a lump sum upon retirement. She can contribute up to $9,500 a year, deferring all taxes. If she starts saving the maximum amount each year beginning at age 42, and continues until she retires at 70, she will have $1,127,185. Even if she stops contributing in the lean years when she pays college tuition, she will accumulate $777,117. (The calculations assume that 25 percent of the assets are in fixed-income instruments earning 6 percent a year and 75 percent are invested in equities earning 10 percent annually.) And in the future, she can use those funds as collateral for a low-cost loan to pay for her children's college education. (Home equity can be another attractive source of such collateral.)

Brown also needs to reallocate her other investments. Most people need just three to six months of living expenses in liquid assets, plus some savings for shorter-range goals. But Brown has 26 percent of her assets in cash, such as money-market accounts--too much when she is not saving for a short-term goal (a down payment for a house, for example). Shifting some of those funds to equities, with their potential for greater appreciation, and diversifying her holdings to include international stocks, could produce higher returns while better balancing her holdings against the risks of volatile markets.

Finally, Brown needs to pay off $5,000 in credit-card debt on which she is paying 18 percent interest. Refinancing her mortgage when market conditions warrant could lower her expenses as well.

All of these changes will help her reach her financial goals. By pursuing a plan like this one, she can provide for her family's needs, while preparing for a comfortable, and financially secure, retirement.

![]()

Professor Harvard, age 68, faces a different set of financial challenges. He earns $115,000 annually and plans to retire in three years, yet needs to make sure he can finance college and graduate school for his two children. His wife, 10 years younger, works as well, earning $58,000 per year. Their house is paid off, and they would prefer to keep it unmortgaged, even though Harvard expects to maintain his family's current lifestyle after he retires.

Given his current financial picture, Harvard could meet all of those goals, says Frederick Putney, author of this hypothetical example, but "it would be tight." Putney, executive vice president and director of Brownson, Rehmus & Foxworth Inc., of Darien, Connecticut, is one of the RPO's outside financial planners. Of Professor Harvard's goals, he says, "If we had a couple of bad years in the marketplace, it could be difficult."

To make things less tight, Putney recommends that Harvard reduce his spending by 5 to 10 percent and invest those savings in equity funds, increasing equity holdings in a mix of assets now weighted 35 percent to real estate and 28 percent to fixed-income investments. When he retires, he will have $1.2 million in retirement funds and another $200,000 in other investment assets, such as money-market funds. In all, he can expect to receive about $94,000 a year to live on ($42,000 from the faculty-retirement plan; $28,000 from a tax-deferred annuity; $18,000 from Social Security; and $6,000 in dividends).

Although he faces less risk of disability than a younger professional, Harvard's family situation suggests the need for life insurance well into retirement, to provide for his children's college and graduate school in case he dies. He also needs to make sure that his spouse takes advantage of her employer-sponsored life insurance to protect against the financial consequences of her unanticipated death. And he will need to continue to teach and consult part-time after he retires, perhaps a bit more than he had planned to, if he wants to meet his financial goals.

"Having a long-term plan gives you the ability to live through the bumps in life and the marketplace," Putney says. Assessing the Harvard family's circumstances, he says, "They were faced with a series of potential risks and they had a nice set of resources, but it was a little tight with respect to carrying out their plan."

![]()

Professor Jones, age 65, is still going strong as chairman of the critical studies department but he, too, looks forward to retiring in three years. His main concern is to make sure that his youngest child, who is severely disabled, will be provided for when he dies. His chief priority must be prudent estate planning.

Jones is a widower, so any inheritance will go to his three children. Excluding real estate, he has $1.6 million in assets and should be able to live at his current lifestyle on $70,000 a year--about 75 percent of his present income. Assuming that his assets earn an expected 7 percent annual return, he will receive about $92,000 a year in pretax income (roughly $63,000 from a 6 percent annual withdrawal from both his tax-deferred annuity and his pension; $15,000 from a 5 percent annual withdrawal from his investment portfolio; and $13,800 from social security). That should be enough to support him as long as he lives.

"What do you need to live off, post-retirement?" asks Joseph Mitchell, vice president and senior account manager for Ayco Corporation, in Albany, New York, who prepared this example. "Most clients have a hazy understanding of what their annual living expenses are. You need to know within $1,000 to $2,000." The financial plan Mitchell has devised shows that when Jones retires, he should first draw upon assets that are not in retirement accounts, because those withdrawals are not taxable. Yet he still has to draw $40,000 a year from his retirement accounts to comply with tax regulations and meet his financial needs. So he will need to set up a regular payment system, such as receiving checks every quarter, in order to keep his funds in the retirement accounts as long as possible, and to keep track of his expenses.

Jones has a few options to make sure that his disabled son is provided for. To minimize the 37 to 55 percent estate taxes on estates of $600,000 or more (no tax is assessed on sums passed to a spouse), he can make untaxed annual gifts to his children of $10,000 each. But he would be giving away $30,000 a year that he might well need if any unforeseen expenses occur, and he would still need to provide for the use of the money on his disabled child's behalf. He could also set up trusts that would pay a certain amount each year to his children, or place his $250,000 life insurance policy in a trust to protect it from estate taxation when he dies. All such trusts, of course, must comply with regulations to qualify for favored tax treatment, and must be properly drafted and administered to satisfy Jones's intentions.

Finally, Jones could also leave his two homes--valued at $900,000--to his children in a trust to reduce estate taxes. Again, doing so would require the help of a skilled attorney and financial adviser, and would involve giving up control over the houses over time to satisfy tax regulations. While Jones may choose not to pursue all these steps, the financial planning process has revealed several options that might enable him to reduce estate taxes by several hundred thousand dollars, and thereby pass much more money on to provide for his dependent son and other children.

![]()

Fortunately, most financial planning techniques are not all that complicated--it's just that most nonspecialists do not know about them. A few examples from real life show what is possible.

Tom Clark Conley, professor of Romance languages and literatures, and Verena Conley, a visiting professor of literature and of history and literature, went through Harvard's retirement planning process when they joined the faculty two years ago. They are both 53 years old. Their two children, aged 28 and 26, have finished their educations but the Conleys are still helping to pay those bills. They are just starting to think more seriously about putting money away for their own retirement. A financial planner they had consulted a few years earlier assured them that their rate of savings was sufficient to pay for retirement. But the Harvard financial planner who ran the numbers "painted a much grimmer picture," Verena Conley says. In response, the Conleys began contributing to the tax-deferred annuity plan.

When they came to Harvard, the Conleys were bombarded by life-insurance agents who told them they needed more coverage. The RPO financial planner told them their coverage was fine. "He said it was better not to let the money wither in life insurance. It was better to invest directly in mutual funds or other funds," Tom Conley says. The planner focused instead on matching assets and goals. "He made us very sensitive to the needs of long-range planning," Tom Conley says. "We moved money from slow-growth funds to faster-growth funds."

Joel C. Monell, 56, dean for administration and academic services at the Graduate School of Education, became interested in financial planning five years ago when he served on a committee that considered offering financial planning services to Harvard faculty members. He went through a mock financial planning process and for the first time gained a clear idea of his assets and liabilities. Seeing it on paper gave him the incentive to pay off about $8,000 in credit-card debt. "I needed someone to sit down and say, 'That's stupid,'" he says. He also doubled his life insurance coverage, which was inadequate to provide for his wife if he died.

Monell has since gone through Harvard's financial planning process himself. He and his wife have no children, so they do not have to worry about education expenses, but they plan to retire to Arizona and would like to do some travel abroad. When he saw the projections of his expected retirement income, Monell realized that he would not be able to maintain his current lifestyle when he left Harvard. As a result, he has increased his contributions to the tax-deferred annuity and moved his assets to more aggressive stocks and mutual funds.

He now meets with fellow faculty members nearing retirement and what he hears is disturbing. "I've discovered that a lot of people don't think seriously about these issues until retirement is almost on them, when of course it's too late to build up your assets," Monell says. "You can't do much if you're just starting to think about it two to three years before retirement."

The planning process primarily "forces you to gather the data, array it in a certain way, and think about it," Monell says. "It's not like there was any great revelation. It was a matter of imposing discipline on an otherwise undisciplined approach."

That's something you can begin to do even without the benefit of a financial planner. Software programs like Quicken make it easy to track your monthly expenses and to calculate the performance of your investments, says RPO's Willson. Many mutual fund companies also offer their customers inexpensive or free financial-planning software packages. Those allow you to project your college savings, retirement income, and other financial priorities based on different rates of savings and asset mixes.

The most important thing to do is to take the first step. "Sometimes people don't invest because they're afraid they don't know enough," Willson says. "It's immobilizing." But, she adds, "Once you decide, 'I'm an investor,' and act like you are, you'll find that it's not rocket science."

Freelance writer Susan G. Parker is a master's degree candidate at Harvard Divinity School.