Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

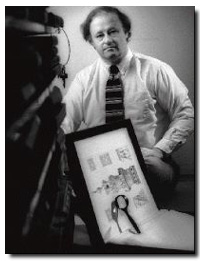

The Harvard College Library hadn't a director of security until 1995, when Louis Derby signed on. He is seen here in the Widener stacks. |

In March 1995, a Harvard graduate student, an Indian woman doing work on Islamic architecture, went to the Fine Arts Library at the Fogg Art Museum and asked for a certain book. It was not where it belonged on the shelf, but it had not been checked out. Library staff searched and could not find it. The student asked to be notified if the book turned up.

Last spring András Riedlmayer, bibliographer in Islamic art and architecture, was looking through the catalog of an English bookseller who lives in Granada and specializes in antiquarian works on the art and history of Islamic Spain. Riedlmayer was searching for replacement copies of a number of books that had gone missing from the Fine Arts Library. He was especially eager to find copies of two portfolio volumes of engravings of the Alhambra and other Islamic monuments in Andalusia, based on drawings by Philibert-Joseph Girault de Prangey and published in Paris in the 1830s and 1840s.

"One reason these two books are important for scholars," says Riedlmayer, "is that they record these monuments before they were greatly altered by repeated efforts at restoration and reconstruction. Girault de Prangey's engravings also played a major role in popularizing the architecture of the Alhambra as the embodiment of Moorish Spain, which had already captured the romantic imagination of nineteenth-century writers like Washington Irving and would inspire Moorish-Revival architecture and decorative design throughout Europe and America for more than a century to follow. These were two works I felt the library should have in its research collection, even if they proved to be difficult and expensive to replace."

Riedlmayer found a number of items of possible interest in the Englishman's catalog, but the star offerings were the same two Girault de Prangey volumes he wanted. "These don't come on the market very often," says Riedlmayer, "so I contacted the dealer at once and explained my interest in these volumes. I also said that we needed them to replace items stolen from our collection. He said that one of the volumes had already been sold to another party, but that he would hold the other one for us. He took a quick look at it and told me with some relief that it did not appear to have any library markings, and thus was not likely to be our lost item.

András Riedlmayer, bibliographer in Islamic art and architecture, at the Fine Arts Library. Business with an English bookseller in Granada, Spain, led to anguish, discovery, and the arrest of Torres. |

"The next morning I arrived at work to find an anguished letter from the dealer in the office fax machine," says Riedlmayer. "Taking a last, lingering look at the engravings in the early morning light, with the sun still low in the sky, he noticed traces of a partially rubbed-out blind stamp at the bottom of one of the plates. Examining the embossed mark with a magnifying glass, he could just make out the word 'Harvard.' Utterly mortified by his discovery, he wrote to inform us at once. We contacted the Harvard police."

With the help of the bookseller in Granada, detective sergeant Richard W. Mederos, who is in charge of the University police department's criminal investigation division, got in touch with a Spanish antique dealer who had sold the Englishman the two books. The antique dealer turned over a list of 41 books that a self-described "private collector" in Cambridge had offered for sale. The antique dealer had bought five books from the list of 41. The seller's name: José Torres-Carbonnel.

Torres, 34, a Spanish national, was married, Mederos discovered, to a Harvard graduate student he had met in Granada. The student turned out to be the woman studying Islamic architecture who had failed to find the book she needed at the Fine Arts Library. The book she wanted for her studies was one of the Girault de Prangey volumes Torres had sold to the Spanish antique dealer.

Torres was known to the security staff at Widener Library. He had attempted, some months before, to leave the library with a book he had not checked out. He had behaved in a sufficiently fishy manner that his library privileges, which he had obtained because his wife was a student, were suspended for a month. During that time Torres asked to meet with Lawrence Dowler, associate librarian of Harvard College for public services. "Torres seemed remorseful," says Dowler. "He said he was a collector and handed us a book as a gift to the library. I accepted it." Dowler now regrets that he took the book and says ruefully that he won't forgive himself for not jumping hard on Torres at that time.

While Mederos was gathering information about Torres, he got an anonymous tip that Torres was intending to move back to Spain for good. On the morning of the day Torres was to fly home, June 25, 1996, Mederos went to Torres's residence, on Pearl Street in Cambridge, and asked him to come to the Harvard police station to talk about overdue books. Torres went with Mederos to the station house, where Mederos and another officer interviewed him. After 45 minutes Torres confessed to having taken from Harvard the majority of the 41 items he had offered for sale.

Why did he confess? "I'm a Catholic," says Mederos. "I laid the guilt on him."

Mederos arrested Torres and charged him with receiving stolen property. Then he got a search warrant and went to Torres's residence, where he found 1,500 items belonging to Harvard-- books and plates razored from books-- mostly from Widener and the Fine Arts Library. They were in cartons, sealed and ready to be shipped to Torres's parents' home in Granada. Their value was later estimated to be $500,000. Mederos also found evidence that other cartons had been shipped to Spain the day before. He asked Interpol to interdict that shipment, which consisted of 200 items worth $250,000.

In its coverage of the arrest, the Boston Globe reported that one of the books Torres sold to the Spanish antique dealer had in turn been sold to the Englishman in Granada for $2,400, and he had sold it to a London dealer for $4,800. That dealer was Bernard Quaritch Ltd. After the Granada dealer notified Quaritch of the possibility that the book was stolen goods, people at that highly respected firm examined it closely, found partially erased marks of Harvard ownership, asked the library for instructions, and sent the book to Cambridge at once. The Granada dealer did the same with the book in his possession. In September Mederos and Marion Taylor of the preservation staff of the Harvard College Library flew to Spain to recover the rest of Harvard's stolen property.

Torres's wife filed for divorce in June, the month he was apprehended.

José Torres-Carbonnel, indicted on 16 counts. |

After Torres was arrested, the judge confiscated his passport and released him on $15,000 bail. A grand jury heard his case on January 30 and indicted him on 16 counts of larceny, receiving stolen property, and malicious destruction of library materials. He was scheduled to be formally charged in Middlesex Superior Court on February 18. If he pleads innocent to the charges, his case will go to trial, perhaps in nine months to a year.

What was his modus operandi? Did he have an accomplice? How much did his wife know? Has all that he may have stolen been recovered? Will answers to these questions be forthcoming?

"Harvard came out in the Globe story looking remarkably good," says Riedlmayer. "The story focused on the positive-- rare items recovered, culprit apprehended--rather than dwelling on the sensational and sad revelation that someone had managed to walk off with many hundreds of rare and valuable items from Harvard's collections without anyone stopping him, and that he might not have been caught at all were it not for a series of truly bizarre coincidences and a few people who somehow managed to put the pieces together and act on them."

Mederos described the materials in Torres's possession as "old books, engravings, and illustrations of Spanish history from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries," the Globe reported. "I felt sick at heart about the losses," says Riedlmayer. "Many of the engravings are plates cut out of books, the mutilated volumes left behind on the shelves with thin, jagged cut edges in the places where the plates had been. Some of the books had been in Harvard's collection for more than a century and a half, used by countless students and researchers who shared with us librarians the task of caring for these volumes, so they could be used by others in the future.

"In a cynical and secular age," he continues, "the destruction of libraries and books is perhaps one of the last acts still almost universally greeted with a shudder, as sacrilege once was. As librarians, we remain mindful of our role as the keepers of memory. We take it personally when someone attacks or tries to steal items in the collections in our care."

An isolated case of theft from a university library? Hardly that. Says Nancy Cline, Larsen librarian of Harvard College, "We are increasingly aware of the extent of theft and mutilation of books occurring in the nation's libraries." The rare books and manuscripts section of the American Library Association maintains a chronological log of incidents of book theft that begins with thefts reported in 1987. While incomplete, it is voluminous. It could give a librarian or a scholar or a simple reader the blues. A dolorous selection:

October 1996. A man charged with stealing historic letters signed by Lincoln and Jefferson Davis from a University of Bridgeport library receives a probation sentence of three years.

March 1996. A North Little Rock, Arkansas, man is arrested for the theft of manuscripts from university libraries in Kansas and Arkansas. His focus was on outlaws, Civil War guerrillas, presidential letters, Martin Luther King, Ezra Pound, and T.S. Eliot. He is sentenced to 15 years in prison.

December 1995. A former student worker at the UCLA library is found guilty of the theft of more than $1 million in books and other materials from its collections.

December 1995. A Florida man who operates an antique map shop is apprehended removing maps from eighteenth-century books at the Johns Hopkins University library. He has obtained stock from at least 13 other libraries. Prosecutors recommend the minimum sentence because of the perpetrator's cooperation in recovering 140 rare documents valued at $200,000.

June 1995. Dutch police arrest a man in the theft of 22 rare manuscripts from Columbia University.

May 1995. Art-history professor Anthony Melnikas of Ohio State University asks a rare-book dealer to sell two handwritten, illustrated pages that appear to have been cut from a medieval book. They correspond with pages missing from Petrarch's copy of an ancient Roman treatise on farming in the Vatican Library.

In this last case, Roger Stoddard, curator of rare books in the Harvard College Library, got into the act. After Melnikas pleaded guilty in Columbus, Ohio, to various charges of mutilating, stealing, and offering his plunder for sale, and while he was awaiting sentencing, Stoddard wrote the court in his capacity as president of the Bibliographical Society of America to call for a hard sentence. "The only real knowledge we can gain about the Middle Ages comes from the close study of the few manuscripts that have come down to us in the great research libraries. Arguments rage about such things as the spelling of a single word, the peculiarities of handwriting of single scribes, or the substitution or replacement of single leaves or sections. In short, we need all the evidence that we can get--scarce as it is, and we depend on the continuing accessibility of old books and manuscripts, so we can test the accuracy of new interpretations....All depends completely on the maintenance and security of library collections: destroy, mutilate, steal, or hide the books and manuscripts and you frustrate the development of knowledge and the free interchange of scholarship and teaching.

"Melnikas has demonstrated publicly how to bring the system down," wrote Stoddard. "He has stolen from us all. Page by page he has destroyed our 'bible' so that we can read only what he leaves behind. He decides what we may use and what we may not. He teaches the lesson. He shows others how to do it."

The judge sentenced Melnikas to 14 months in prison, two years of supervised release, 250 hours of community service, and a $3,000 fine, and ordered him to pay for the return and restoration of the things he stole.

| "The Slasher" | Student, Teacher, Scholar | Caging the Man-eaters |

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()