![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

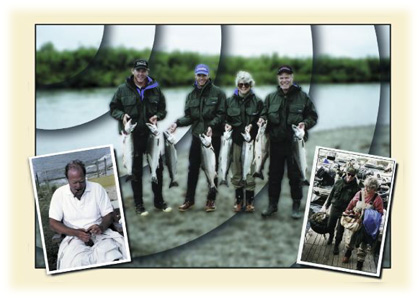

At the Kanektok River in Alaska, Zachary, Grant, Lulie, and Gordon Gund hoist salmon they have caught. On Nantucket, where they have a home, Gund works on a woodcarving of a fish (left inset), and he and Lulie return from a successful quahogging expedition (right inset) |

Gund was able to see his son Grant, born in 1968, but by the time Zachary appeared two years later, his father could not view the infant's entire face at once. Gund could, however, create a visual gestalt by scanning across a face, and gazed at his two boys all he could, since he knew that before long he might never again see his children. In 1970, his macular vision deteriorated rapidly and he went from having about 75 percent of a normal visual field to almost complete blindness in only a few months. "There were differences even from day to day," Gund recalls. "At one point I could pick up, say, the Wall Street Journal and take in a whole paragraph at a gulp. Then I could see only a sentence at a time, then a word, then only single letters. I could actually measure it, and it made me frantic to find something that would help."

Newton Merrill '61, a close friend, says that Gund "sought out every possible solution. He was turning over every stone." Gund had both the motivation and the monetary resources to pursue all possibilities. (His father, Cleveland investor and banker George Gund '09--for whom Harvard's Gund Hall is named--had secured his family's financial future by acquiring the American rights to a Dutch decaffeinated drink called Kaffee Hag in 1917; over here, the product eventually evolved into Sanka.)

Gund played his last card, a long shot, in November 1970. With the help of Elliot Richardson '41, LL.B. '44, he obtained a visa to go to the Filatov Institute on the Black Sea to try an experimental treatment for RP that involved attempts to stimulate the retinal cells with ultrasound and injections of animal biostimulants. The hospital was a czarist-era building in a state of advanced decrepitude--paint peeling from the walls, bare light bulbs, toilets that did not flush, and hot showers only once a week. Russian medical science was equally unprepossessing; the treatments, for example, involved 10 to 12 injections daily, often into the temples, that site apparently chosen on the fanciful notion that something added to the bloodstream had to be injected near the tissues one intended to affect.

Lulie Gund had just given birth and could not travel; brother Graham Gund, M.Arch. '68, M.A.U. '69, one of Gund's five siblings, accompanied him to Russia. But in Odessa they learned that, instead of a few days, the treatments would take four weeks. Professional responsibilities compelled Graham to return to the States. Gund was alone and newly blind in a strange country; he could not even get a phone call through to the States. "Nobody spoke English, and I had no Russian," he recalls. "Since I could not see, sign language was not a possibility. I had to go right down to the basics within myself. Learn where the bathroom was, where to go for treatments. I wasn't going to get a meal unless I could find out how to get to the dining hall and what the food was. I had to come to grips with the fact that the sighted part of my life was over, and the new part beginning. A big thing is the anxiety about the unknown. If you lose your sight from an accident, you don't think about it, but with progressive degenerative diseases, there's the stress of wondering what is coming."

There was no wondering about parenthood; infant Zachary and toddler Grant awaited him at home. Luckily, there was also Lulie, an upbeat, resilient woman who has surely been Gund's greatest asset. "Were it not for her, I would not be doing much of what I do," Gund says. "She makes sure I don't get either too down or too cocky." Zachary Gund says, "My parents have amazing communication with each other; they have signals for everything. They do things that even Grant and I don't know about." Shortly after Gund went blind, he and Lulie hosted a summer barbecue for some friends. "Gordon was putting the steaks on, but he forgot to put the grill in place and dumped the steaks straight onto the coals," Mike Deland recalls. "Lulie started to get up to help him but thought better of it and sat down instead. She realized that if Gordon had to go through the process of retrieving the steaks off the coals, he would never forget that grill again."

There are programs that use blindfolds to train people who are losing their vision for a sightless existence. But "Gordon was never interested in the idea of learning how to be blind," says Graham Gund. Instead, as Lulie puts it, "You don't limit your life to the problem you have. You learn to get your life to work. You just find new bridges."

Bridges like super-acute hearing: longtime friend Bill Polk, headmaster of Groton School, recalls a gathering at the Gunds' Nantucket house, where Gund alerted the others present to some beautiful bird calls--calls that no one else could hear. During Zachary Gund's childhood, "Other kids would sometimes say, 'Gee, you're so lucky--your father can't see, so if you get in trouble you can just hide on him.' It didn't work that way. Dad's sense of hearing is so acute that you could sit in a room and he would hear you breathing--and he'd even know who was breathing." Deland, who suffers from chronic back pain, notes that on phone calls with Gund, "He can tell by my tone of voice that it's a day when my back is really stirred up. Nobody else in my life has been able to do that."

Astonishing mental powers are another kind of bridge. "Right after Gordon lost his eyesight his memory dramatically changed," says Graham Gund. "His ability to remember things is staggering. If he were hosting an event where he didn't know people, and maybe 30 or 40 new people came up and shook his hand, at the end of the evening when they were leaving he could tell you who each one was." Gund routinely prepares for board meetings by memorizing all relevant documents, including financial statements, and can perform amazing feats of calculation in his head. "During our [Groton's] capital campaign, we would all be sitting around with our calculators out, looking at spreadsheets," says Polk. "Gordon just used his head and he'd be right on the dime."

Gund's rich sense of humor also transcends sight. Gund sometimes ice skates with his sons on a pond behind their Princeton house, showing some of his previous skill as a hockey player. "I can still skate pretty well," he once told Newton Merrill. "But, damn! I just don't make a good goalie anymore." A woman once approached Gund at Aspen and said, "Why do you wear that vest that says blind skier? I've watched you ski and you obviously are not blind." Deadpan, Gund replied, "It's because I like to ski with my eyes closed." Contented, the woman went on her way.

Gund, however, is quite serious about the Foundation Fighting Blindness, which the Gunds and Beverly and the late Ben Berman (whose two daughters were diagnosed with RP) launched, along with others, in 1971 as the National Retinitis Pigmentosa Foundation, to fund research into the disease. At that time, "there was very little interest in diseases that related to quality of life," says Graham Gund. "The government was funding research only on things that were life-or-death issues." In 1994, the foundation changed its name to better reflect its longstanding focus on the whole family of retinal diseases that affect the photoreceptors (see "Visionary Research").

The foundation's philosophy reflects Gund's outlook as a venture capitalist. "We've always tried to provide seed capital," he says. "We help get new efforts going and--if they are successful--the National Eye Institute [a branch of the National Institutes of Health], which has much greater resources, will fund them. In 25 years the foundation has raised more than $100 million, and funded more than $75 million in research--and I would bet that, as a result of that funding, those research institutions have ultimately received four to five times that amount."

If Gund's loss of sight was a case of terrible luck, what he has done with his blindness is quite the opposite. "He was always a wonderful friend and a great companion--disciplined, fun, hardworking. But you didn't see him as someone who might become, say, CEO of General Motors," says Stewart Forbes '61, another college roommate and longtime friend. "It wasn't until he experienced his blindness that he became extraordinary. Now there's no limit to his capacity to take on a task, to lead and to relate to others. He realizes that through his blindness he discovered abilities he never knew he had. Consequently, he has a tremendous belief that each individual has a vast reservoir of untapped skills and capabilities."

Take skiing, for example. "I'm a better skier now than I ever was sighted," Gund says. For the last 16 years, he has skied with Aspen instructor David Elston. Elston skis directly behind Gund and gives him verbal directions as needed; raw athletic ability and the feel of snow and slope take care of the rest. They tackle trails up to the black diamond (expert) level and have had no serious accidents. "He's a better skier than 75 percent of the people out there," says Elston. "He's strong, aggressive, in good shape, and he knows how to use his edges. Gordon carves his turns, he doesn't skid through them."

Two years ago, NBC broadcast a short spot on Gund's skiing exploits during half-time of a Cavaliers game. He explained that the sense of freedom was, for him, a big part of the exhilaration: "When you are blind you are limited, most of the time, to the extension of your arms and your hands, so your space is pretty closed in. When you get out and can move as freely as this and as fast as this without holding on to anyone...it's really very special, because you don't get to do it very often."

A couple of years ago Gund and Elston skied down a black diamond trail that featured plenty of big--18-inch-high--moguls. Gund skied a flawless route down the mountain, gracefully following the fall line. "He skied it as if it were flat," Elston says. When they arrived at the bottom, Gund turned to Elston, puzzled: "I thought you said there were moguls?"

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()