![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

| This article, previous... | ...or see related articles |

![]()

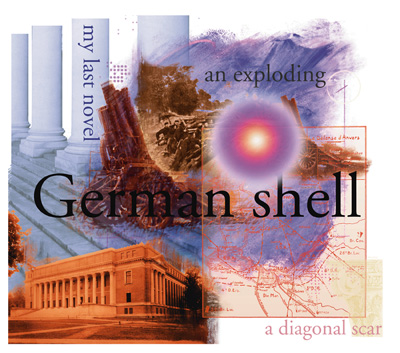

Widener has not only nourished my scholarly side; it also helped me write my last novel--and filled in some gaps in my family history. My father fought in the Belgian army in 1914. He was wounded in the head, the chest, and the legs by an exploding German shell before Antwerp, picked up on the field of battle by British litter bearers, and taken to London, where he spent three years in a military hospital in Chelsea. In 1917, discharged from hospital and the army, he came to this country, bearing over his right eye a diagonal scar at the place where his skull never healed from the shrapnel wound.

He seldom talked about the war. I lent him my copy of Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August once, but he returned it after reading a hundred pages. "I do not want to remember it," he said. On occasion I could pry out of him a few details--that he had been in the field army when the Germans bombarded the forts at Liège and that the flames from the dropping shells had sent fire 500 meters into the sky, that his part of the army retreated through Louvain shortly before the Germans destroyed the priceless library of the old university there, that he had been in the artillery before the Germans captured his gun, that he was wounded on 28 September 1914, that he remembered only a blinding flash, that he was lying behind a railroad embankment when the shell burst, that he was picked up by English soldiers at night who heard him cry out in the dark when he recovered consciousness.

When I decided to write a novel loosely constructed on his life, I wanted in my skeptical way to verify the few details he had given me. Down on level B West of Widener were shelves of books, many covered with dust, telling in detail the story of the Belgian army in 1914 and its dogged fight and retreat before the German juggernaut. I blew off the black dust of huge, illustrated tomes such as L'Armée belge dans la guerre mondiale (with maps and photographs), and I was able to trace his approximate course across Belgium to his destiny. Yes, fierce fighting went on in the railyards outside of Antwerp, and 28 September 1914 was a particularly bloody day. I learned a detail that my father had not told me--that rain poured down all that day and that the soldiers' boots were heavy with mud. I scanned the photographs--including one of Belgian soldiers crouched with their rifles and waiting behind an embankment outside of Antwerp--and I studied the maps, inconclusively, of course, but feeling a certain closeness to a young man I had never really known. Some of the details went into my novel, published in 1992 four years after my father's death; some stay only in my heart.

| This article, continued... | ...or see related articles |

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()