![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

The Child Specialists

Several endangered or extinct species haunt college sports today, hovering like ghosts over playing fields, courts, pools, and courses. Clearly, the rise of recruiting has killed off the "walk-on," the varsity athlete who was not

Head coach of men's basketball Frank Sullivan. Last year his squad recorded more wins than any Harvard team in half a century.Photograph by Erik Fowke

Head coach of men's basketball Frank Sullivan. Last year his squad recorded more wins than any Harvard team in half a century.Photograph by Erik Fowke |

Fencing is an exception, at least at Harvard; coach Branimir Zivkovic's squads of nine men and eight women fencers are about half walk-ons. "Fencing opens the door to all those who can't make it in the sport they love," Zivkovic says. "Maybe you weren't quite good enough to make the tennis team; perhaps you love basketball but are a midget among the giants. But you are still an athlete, you are competitive, it's in your heart and blood. You try fencing, a combative sport that demands everything."

But in most sports, walk-ons are disappearing because higher levels of performance generally build on greater depth of experience in the particular sport. Hence, another endangered species: the "three-letter man." This phrase dates from the era when the operant term really was man--before 1972, before Title IX and the explosive growth of college women's athletics.

The classic three-letter man was the campus hero who earned varsity letters in football, basketball, and baseball--an all-around athlete. He has disappeared. There are about 1,300 varsity and junior-varsity athletes at Harvard, but for the past two years, none of these 1,300 have played three sports. In the 1994-95 season, seven men and three women did pursue three intercollegiate sports. Those 10 may have been the last vestiges of the triple-threat species at Harvard. Even the two-sport athlete is becoming rare. Over the last three years, only 110 to 180 Harvard students per annum played on two intercollegiate teams. In other words, 85 to 90 percent of Harvard's athletes are single-sport specialists.

This trend does not begin in college: secondary-school and even primary-school students are specializing in one sport only--and doing so at younger ages. "There's this thrust toward specialization at all levels," says men's basketball coach Frank Sullivan. "Parents feel that their children have to specialize, or they won't be as good as the rest of the kids. So they wind up playing soccer all year, or basketball all year. There are loads of clinics and camps, run by entrepreneurs."

Even within a given sport, youngsters are narrowing their focus. Costin Scalise recalls that when she began coaching, "You could train people and have them swim a lot of different events. Now you have to recruit specialists for each event."

Many Harvard coaches lament the specialization trend, even as it brings them more accomplished--if less versatile--recruits. "It's unfortunate, because the greatest thing is to have kids do everything they can," Murphy says, adding, "We are trying to identify the talented at ages when their talents may not yet have appeared." Director of athletics Bill Cleary '56 recalls, "When I was a student at Belmont Hill [School], they made you play a different sport in every season. I think that's healthy." As Harvard's men's ice hockey coach from 1971 to 1990, when Cleary was recruiting players he "always looked to see if they played another sport--because you win with athletes."

John Dockery '66 lettered in football, baseball, and indoor track at Harvard, then played cornerback with the New York Jets, becoming the only Harvard man to win a Super Bowl ring (in the Jets' fabled 16-7 triumph over the Baltimore Colts in 1969). He is now a sports commentator for NBC Television and CBS Radio. "If I were applying to Harvard today, I guess I'd be just a football player," he says. "I think that would have diminished my enjoyment of sports and even my development as an athlete. The quickness I got from running track, for example, definitely helped me on the football field, and also the baseball diamond."

The adult takeover of children's sports is a key factor driving specialization. Where there was once sandlot baseball, there is now Little League, with teams that wear uniforms, play schedules, have business sponsors--and where kids play assigned positions. Street kickball has given way to heavily coached youth soccer teams. "There's no pickup football or basketball anymore," says Murphy. "Everything is organized by adults. The whole society has become more competitive, with the emphasis on specialization. But kids would not specialize without the parents' pressure."

According to Patricia Henry, senior associate director of athletics, "Some parents become shortsighted. Everybody's grabbing for that brass ring, for their kid to become an Olympic athlete. It's not just in sports; you see it in music, the arts, everywhere. Everybody's got to be a genius, a millionaire, be 'the best that they can be' by age 10. Kids don't have a chance to grow up. With television, computers, piano lessons, schoolwork, and soccer practice, they just don't have any downtime."

Adults have also built competition, with its accompanying anxieties, into what used to be children's play. "I don't think winning is the important thing at young ages. I'm not sure you should even worry about playing games until you are 15 or so," says Cleary. "At age 9 my son would play a one-hour hockey game; he'd be on the ice three times a period. Maybe each kid would touch the puck once per shift--for a few seconds. My philosophy is: give everyone a puck and just practice for an hour. How do you build up your skills if you don't touch a puck? I never had a uniform on until I was a sophomore at Belmont Hill." (Competitively, Cleary's "pond ice" approach to learning hockey did not serve him badly: he still holds Harvard's single-season scoring record--42 goals and 89 points in 1954-1955--and was on the U.S. hockey team that won an Olympic gold medal in 1960.)

Will Kohler '97, the 1996 Ivy League Player of the Year and a Second Team all-American.Photograph by Tim Morse

Will Kohler '97, the 1996 Ivy League Player of the Year and a Second Team all-American.Photograph by Tim Morse |

Another soccer star, Naomi Miller '99 of San Antonio, had basketball practice four afternoons a week until 6:00 p.m., when her mother picked her up and drove nearly two hours--while Miller did her homework--to Austin for practice with an elite girls' soccer club. After the 90-minute practice, they drove back, getting home by 11:00 p.m. Grueling, yes, but it helped Miller develop into the striker who last year led the Ivy League in scoring. Her teammate Stauffer cites other sacrifices: "Not going out on a weekend night with a friend because you had a game on Sunday, not going to the beach on a weekend because you have a tournament." However, she adds, "I'm glad I made the trade-off."

Not everyone makes it. By age 12, Meredith Rainey '90 was already nationally recognized as a fast runner. "I knew I had talent in track. My coach told me I could get a scholarship," she recalls. "But after a few years, I didn't enjoy the sport; I expected too much of myself. It was a little too intense for me at that age, the pressure of competing at a national level. I enjoyed team sports more." So in high school Rainey played volleyball and basketball instead; she had fun, but did not star. At Harvard, she returned to track and became one of the most spectacular walk-on successes in school history. In her junior year, she won the NCAA Championships in the 800-meter run and as a senior, became the indoor NCAA 800-meter champion while breaking the collegiate record. Rainey has been ranked among the top three female 800-meter runners in the United States every year since 1991, and was on the 1992 and 1996 U.S. Olympic teams.

Few will reach Rainey's level, but there is no question that specialization generally produces stronger athletic performance at younger ages: witness the world's top-ranked woman tennis player, 16-year-old Martina Hingis. Today's youths are bigger, stronger, faster, and they have better nutrition, better equipment, and more experience. Track and field coach Haggerty notes that many Harvard records have fallen in the last 10 to 15 years.

But some things have also been lost. "Performance might be better now, but the depth of performance is not better," Haggerty says. "We used to have two or three good discus throwers, not just one. There were bigger track teams in the 1960s, more people competing at a high level." In men's tennis, coach Dave Fish says that, "With the kind of teams we have now, 20 years ago we'd have been in the top 10 nationally." (Last year the Harvard squad had an excellent season, and was ranked nineteenth in the nation.) That is the good news. "The bad news," Fish says, "is that very competitive high-school players come here and cannot get a spot on the varsity or JV teams."

The Endless Season

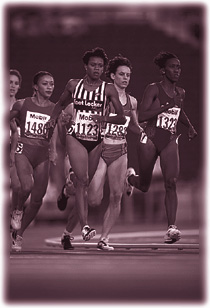

Meredith Rainey '90 (center) at the 1996 Olympic trials.BRIAN MYERS „ PHOTO RUN 1996

Meredith Rainey '90 (center) at the 1996 Olympic trials.BRIAN MYERS „ PHOTO RUN 1996 |

If you are a single-sport specialist driven to perform at the highest competitive level, your season gets longer. Not only because of postseason tournaments and preseason games and perhaps a longer regular-season schedule--but because off-season training has become de rigueur. If everyone else is doing it, how can you afford not to?

"All sports are being extended," says Bill Cleary. "When I played, we didn't start hockey until December 1. Now, practice starts October 15--and we [Harvard] are the last ones." Five years ago, the Ivy League began allowing out-of-season practices: coaches can now conduct a limited number of spring football and soccer practices, for example. And athletes work on strength and endurance all year long, weight-lifting and running.

The "season" itself now runs all year, in one form or another. Rowers can finish their fall racing with the Head of the Charles Regatta, then train on rowing machines for the World Indoor Rowing Championships in February before the Charles River thaws and the spring and summer crew seasons begin. Indoor facilities, air conditioning, and artificial turf have helped eliminate rain, wind, sun, cold, and mud--in other words, nature--from sports. You can play indoor soccer all winter long, or ice-skate in August in an air-conditioned hockey rink.

In contrast, Char Joslin '90, M.B.A. '95, had a busy but varied career, earning varsity letters in three sports--field hockey, ice hockey, and lacrosse--in each of her four years at Harvard. She had captained the same sports and earned 12 varsity letters at Groton, where in her first year she rose early and studied in her closet using an Itty Bitty Book Light, so as not to disturb her roommates. At Harvard, one difficult thing was the three consecutive seasons of weekend road trips for games--leaving Friday morning, returning Saturday at midnight, and recovering on Sunday. "You never have a whole weekend off," she says. NCAA rules that restrict time slots for off-season practices helped Joslin. "I wouldn't have been able to keep up with off-season training," she says. "In lacrosse, for example, I had to miss 'fall ball.'"

Both Harvard and Ivy League policies give regular-season practices precedence over off-season training. So, for example, a two-sport athlete like Peter Albers '97, who played varsity soccer and baseball would, in the event of a conflict, go to baseball practice rather than a spring soccer scrimmage. That is the official policy. But subtle or overt pressure from coaches, parents, teammates, and the student's own inner expectations may influence the young athlete to drop the second sport in favor of the "main chance"--competitive excellence in one's specialty. Five years ago, Harvard's intercollegiate teams had a total of 1,500 athletes; that number has since fallen by more than 10 percent, to 1,300. One reason is that JV rosters shrink as athletes drop their second sport to concentrate on the primary one.

Off-season training saps energy not only from other intercollegiate sports, but from intramural sports as well. In addition to its 41 varsity sports, Harvard has 27 intramural leagues, which have long been a cherished part of undergraduate life. Varsity athletes, during their off-season, often were leaders on the house teams that compete for the Straus Cup. "If you had two varsity baseball players in Dunster House, they might get five or six other guys off the couch to play touch football in the fall," says associate director of athletics John Wentzell, who oversees Harvard intramural, club, and recreational sports. "Now they can have 12 two-hour baseball practices in the fall--plus skills practices, conditioning, weight-lifting. So instead of playing six games of touch football, they wind up doing something baseball-related. Varsity athletes are becoming a more isolated group, not rubbing shoulders as much with those outside their sport."

Admissions dean Fitzsimmons notes that "The year-round nature of some sports prevents not only a second or third sport, but other extracurricular activities, or the opportunity to get to know a much broader range of students here. At its worst it can get in the way of academics--passing up that afternoon class that conflicts with practice. Some athletes become 'prisoners of sport.'" He adds, "A narrowness can be engendered by having an activity that dominates a person's life; it becomes a much larger component of someone's identity. It's a much greater loss if they don't make the team, or get hurt and can't play. The whole persona can be developed around that one activity."

The final price of the relentless training may be charged against the athlete's body. "The basis of most injuries is overuse," says Haggerty, the track and field coach. Like most serious squash players, Harvard's number 1 man, Daniel Ezra '98, trains 10 months a year. He has dislocated his right shoulder numerous times; while lifting weights during the summer before his sophomore year, left-handed Ezra favored his right side while, as he says, "jumping into heavy weights too fast." Unfortunately, he damaged a rotator cuff muscle and could play no matches from November through January. Still, he stayed fit with lots of running and by February bounced back to win the individual national championship, beating teammate Joel Kirsch in the final.

Ezra's predecessor at number 1, Tal Ben-Shachar, also won national titles, in part by becoming one of the fittest squash players alive. In high school, Ben-Shachar ran 60 miles a week in addition to playing squash. But he also suffered hip, groin, and back injuries that at one point kept him out of squash for a year. Since American college squash has switched to the international game--a bouncier ball, a larger court--points have become longer (30 to 50 hits rather than 10 to 20) and endurance is a bigger factor, especially at the top levels. "Everyone has decent shots," Ezra says. "Squash today has become about fitness. Everyone pushes it a little further. There was a British professional a few years back who trained by running until he vomited--and then running back from that point. Look at the number of sports records that have been broken in the last few years--are there really that many great athletes? It seems that the ability to endure pain is increasing every year."

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()