![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

| |

|

Let us begin with a period piece: a story that was startling when it happened, but today would be beyond startling, because it could not occur. In the fall of 1965, at freshman registration, Jack Barnaby '32, then head coach of tennis and squash, sat behind his table in Memorial Hall, hoping to interest these freshest of freshmen in racquet sports. A young man who had come to Harvard from Bombay, India, approached and greeted Barnaby politely in British-accented English: "My name is Anil Nayar and I would like to try out for your squash team." The coach learned that Nayar had played squash, and invited him to Hemenway Gymnasium to hit a few balls and talk further.

At the gym, Barnaby asked Nayar if he had played competitively. The freshman said yes, so Barnaby inquired, "How did you make out?"

"I won," was the simple reply.

"Oh--were you the junior champion of India?" Barnaby asked.

"I have been the men's champion of India," Nayar explained, "for the past two years."

After Barnaby recovered his composure, he assured Nayar--who went on to play at number 1 for Harvard's squash team and won the national intercollegiate singles championship three times--that there was a red carpet in the squash office and he would be glad to roll it out at any time. Later, Barnaby asked an admissions officer why they had kept the young champion a secret. "We thought you'd find it a very pleasant surprise," was the answer.

The days of such surprises are over. Today, squash coaches would spot an athlete of Nayar's caliber years before he applied to college and all American schools with varsity squash programs, including Harvard, would vigorously recruit him. College sports in general, including the Ivy League, have changed radically since 1965. Long-established amateur traditions, guided by patrician rules and played out on pastoral fields, have given way to a complex, highly competitive, multibillion-dollar enterprise, shaped by the values of business and professional athletics.

In this rapidly evolving context, the mainstream of American college athletics has moved away from the Ivy League's classic ideals about the proper role of sports in higher education. And within the Ivy League, Harvard represents the staunchest holdout for amateur values that are under increasing attack, from sources both within the league and beyond it. The recruitment of athletes, their development before college and their training and competition once enrolled, their character, and their distribution among sports--are all in flux.

The choices we make about the future of intercollegiate sports ripple out far beyond the academy. College sports priorities affect not only professional athletics but, more importantly, the lives of students in secondary schools and even children in grade schools. A society's heroes reflect its values, and whether we like it or not, many of the world's most influential heroes are now athletes. "The whole society has shifted," says head tennis coach Dave Fish '72. "In the 1950s, when they asked high-school kids what person they most admired, it was Albert Schweitzer. Now, it's Michael Jordan."

The Recruiting Wars

In Tampa, Florida, in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, in La Jolla, California--all over the country, on July 1, the phones begin ringing, the mailboxes fill up, the fax machines hum happily. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) prohibits recruiting contact before the first of July, but then the floodgates open. Interestingly, although the NCAA limits coaches to one phone call per week to a given athlete, it permits an unlimited number of faxes or e-mail messages. The communications blitz zeroes in on college-bound high-school juniors who have shown athletic skill, and it is vigorous. "Look at high-school students--very few are especially scholarly, nor are they particularly athletic," says head football coach Tim Murphy. "Those with both talents are pursued by American colleges with tremendous intensity and skill." Teenage athletes whose academic credentials qualify them for Ivy League colleges are doubly desirable, and this elite group gets an ardent courtship.

In the summer of 1993 the blitz hit Emily Stauffer '98, of New Canaan, Connecticut. Stauffer's under-17 team from the Connecticut Omni soccer club had won a national championship that year, and on July 2, when she returned home from a trip, there were 24 messages from soccer coaches on her answering machine. By then Stauffer was used to seeing coaches with clipboards sitting in beach chairs, lining the sidelines at games where she and other strong young players were competing.

Harvard women's soccer coach Tim Wheaton had known Stauffer since she was 13; he had coached in a regional program where she played and coincidentally, Wheaton had moved up through the junior-soccer age groups as a coach in parallel with her. Many other coaches were in the hunt for Stauffer, including Anson Dorrance of the University of North Carolina, who had taken a team to victory in the women's World Cup. "It was known in the soccer world that playing for Anson greatly helped your chances of making the U.S. Olympic team," Stauffer says. Although generous athletic scholarships were available at North Carolina and elsewhere, Stauffer's family didn't need the money. She explains that even if she had attended a "scholarship school" like North Carolina, her family would not have accepted a scholarship, "because my parents feel that the money should go to kids who need it, not because they play soccer."

That is a succinct statement of the long-established "need-based" financial-aid policy at Harvard and other Ivy schools. But among 300-odd colleges playing Division I athletics, only the Ivies forgo athletic scholarships (see "The Athlete Auction,"). Jay Saunders, assistant coach of women's soccer, says, "Most of our players turn down [athletic] scholarships to come here."

|

|

| Head football coach Tim Murphy (above) and squash magician Victor Niederhoffer '64. Top photo by Tim Morse |

Stauffer was among them: although she initially expected to attend Brown or Duke, she ultimately enrolled at Harvard, where she has concentrated in government. In soccer, she has starred as a midfielder since her freshman year: she has been Ivy League Player of the Year for the past two seasons, sparking a team that last year went undefeated in the conference and was ranked as high as tenth in the nation. This fall Stauffer is cocaptain of a squad that may be even stronger.

The success of Stauffer and her teammates proves that Ivy coaches can achieve national success without athletic scholarships. The Harvard men's soccer team also thrived last year, reaching the second round of the national tournament and ranking number 12 nationally. When the NCAA recently rated the overall caliber of play for all 21 conferences that play men's soccer, the Ivy League was second only to the southeastern Atlantic Coast Conference.

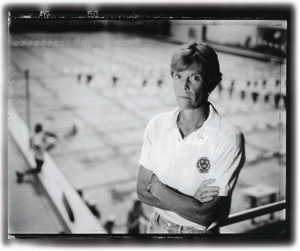

But that kind of success depends on recruiting, the activity to which most Harvard coaches now devote the largest share of their time: Wheaton, for example, estimates it at 80 percent, in one form or another. Maura Costin Scalise '80, who coached women's swimming at Harvard from 1984 until this year, says, "In the sport of swimming, I'm only as good as the athletes I bring in; 95 percent of my success is due to recruiting."

It was not always thus. Until the mid-1970s, institutional policies and gentlemen's agreements minimized recruiting within the Ivy League. Harvard had especially stringent guidelines against it: "We didn't recruit, period," says Barnaby. The policy forbade coaches to talk with prospective students unless the student had first contacted Harvard. "I always felt that someone should be grateful to attend the College and that it was a privilege to play for Harvard," Barnaby recalls. "I wasn't going to get down on my knees and beg anyone to come here, no matter how good he was." Fish, who was Barnaby's protégé, explains that, "to Jack, recruiting was a dirty word. When I was in college, to recruit implied that you were lazy: the assumption was that if you recruited, you didn't coach."

In those days, "recruiting" often meant persuading undergraduates to take up a new sport. Former Harvard diving coach John Walker got gymnasts interested in diving--and produced some of the best diving squads in the country. Barnaby urged his tennis players to consider squash. "For 20 years, I never had a varsity team without a Harvard beginner on it," he says. "I always figured that if I could teach the game, the Harvard admissions office would make sure I got a lot of people with brains who could learn well." One memorable beginner was Victor Niederhoffer '64, a tennis player who learned squash at Harvard and went on to become one of the greatest squash players in history, winning the national intercollegiate championship in his senior year.

Those were the days: imagine teaching a new sport to a college student! Today's top squash players are often national champions before they enter Harvard. For example, Jonny Kaye '92, M.P.P. '95, Tal Ben-Shachar '96, and Joel Kirsch '97 won a combined total of 10 Israeli national titles in squash before matriculating.

In recruiting, Harvard has responded to what other schools were doing--often out of competitive necessity. Costin Scalise explains that "today, everyone recruits so aggressively that if you don't do it, the students think you aren't interested in them. In 1996 I lost six recruits to Stanford; I had done home visits with three of them. The Stanford coach did second home visits; he crossed the United States to see them again when he learned they were wavering or leaning toward Harvard."

For a long time Harvard had a rule that coaches could not go on the road to recruit, although the rest of the Ivy League had no such prohibition. "We never could get anyone else to go along with it," says associate vice president for University relations John Reardon '60, who was director of athletics from 1977 to 1990. "We felt our alumni could give a kid a lot better picture of what Harvard was about--the totality of it--than a coach. The coach is primarily interested in somebody for their sports abilities."

Maura Costin Scalise '80 reigned over Blodgett Pool as head women's swimming coach from 1984 to 1997. Photograph by Erik Fowke

Maura Costin Scalise '80 reigned over Blodgett Pool as head women's swimming coach from 1984 to 1997. Photograph by Erik Fowke |

But that Harvard policy disappeared after a 1987 NCAA ruling that prohibited alumni from contacting potential recruits. The NCAA was reacting to abuses by certain booster organizations and overzealous graduates; such interactions do improve the possibility of money changing hands, including outright bribes to attend a given college. At the NCAA meetings, Reardon argued against the change, saying that if someone wanted to give an athlete money, it was hardly necessary to have direct contact to do so. Penn State football coach Joe Paterno, himself a Brown alumnus, countered that Harvard and the Ivy League were living in "a fairy-tale world." Ultimately the rule went through, hurting Harvard more than most colleges, since Harvard's alumni network for recruiting undergraduate applicants is especially well-organized. Today, a Harvard graduate who spots a promising high-school athlete can do no more than give the student's name to the appropriate coach.

Hence, the recruiting burden now falls more squarely on coaches' shoulders. After identifying potential recruits, they begin the arduous process of screening, tracking, following up, and courting them. Men's soccer coach Steve Locker sees 1,000 players per year, watching up to six games in a day: one format is the "showcase," which might mean traveling to Cincinnati, Ohio, to spend a Saturday watching soccer from 8:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. with 150 other coaches. Diving coach Keith Miller monitors about 75 recruits with a software program that is designed for people in sales. In fact, the process of identifying and qualifying prospects, retrieving information, and logging the results of contacts closely parallels a sales relationship--in essence, it is one.

The football brochure has enlarged from 6-by-9 to 8 1/2-by-11 inches, which might parallel the growth of recruiting in coach Tim Murphy's life since he came to Harvard in 1994 after coaching at the University of Cincinnati and the University of Maine. "A lot of people think this job means less recruiting, but actually it's more. Recruiting here is longer, harder, and more labor-intensive," he explains. "At Cincinnati and Maine you had a good regional base within 250 miles. At Harvard we literally go to the four corners of the United States to find 35 recruits. There's not a football program in America that travels as much as we do."

Football is not like track or swimming, where a coach can screen prospects by examining winning times in a 400-meter race. "Everything in football is very subjective," Murphy explains. Context matters. One current Harvard player, for example, came from a Nebraska high school that graduated a senior class of 40 and played "eight-man" football against other small high schools.

Because NCAA rules forbid coaches to go on the road recruiting until December 1, when the high-school football season is over, college coaches cannot see their prospects play "live." Instead, the Harvard football staff begins with a database of 4,000 videotapes, dossiers, and transcripts, which they winnow down to the top 1,000 prospects who may have a chance of admission. They apportion these among the five-man staff and narrow the pool to 100 by the Christmas break. Between then and March 1, Murphy tries to meet all these boys in person. For those winter months, his family sees little of him. "I'm on the road five days a week--and even on weekends, I'm here at Harvard, seeing student-athletes who are visiting the campus," he says. The football staff submits its final list of prospects to the admissions office, identifying the athletes they like who appear to be academically qualified. That last is the rub: what it means, says Murphy, is that "we have the smallest recruiting pool of any college."

|

|

| Two mentors: the women's soccer team's Tim Wheaton (above) and track coach Frank Haggerty.

Photographs by Tim Morse |

Varied admissions standards within the Ivy League do create certain inequities on the playing field, though less so than in years past. In the 1970s, Jack Barnaby spotted a squash player at an Eastern prep school who, in his judgment, was the best junior to appear in the United States in 10 years. He wrote a note to Harvard's admissions office saying, "This guy is not just great--he is Great with a capital G." But some time afterward, an admissions officer saw Barnaby at lunch and told him, "I'm afraid we've got some bad news for you, Jack. It turns out that your squash genius ranks 65th in a class of 70, and we've already turned down several of his higher-ranking classmates. We can't admit him." Not long afterwards, Barnaby learned that Princeton had offered early admission to his prospect, who went on to play for their men's squash team.

The story has a coda: while this boy was indeed the best junior in the United States, he was not the best in North America. A young Canadian, Michael Desaulniers '80, matriculated at Harvard that year and beat everyone in intercollegiate squash every time he played. With the exception of one year when Desaulniers was injured, he completely dominated American college squash as a undergraduate; for Harvard, he lost only one game, never mind a match.

But that was before the Ivy League adopted the "academic index," a method of insuring that recruited athletes' academic credentials reasonably approximate those of their college as a whole (see "Team Transcripts," November-December 1996, page 72). The index combines Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) scores, class rank, and achievement test scores to create benchmarks for each college's incoming classes, and requires recruited athletes to fall within one statistical standard deviation of the class average, and to meet a minimum academic level. The idea behind the index, says dean of admissions and financial aid William Fitzsimmons '67, Ed.D. '71, is that "We did not want a separate athlete population."

Despite this, the recruiting dynamic itself can also segregate athletes and apply a lingering pressure on them after they matriculate. "Coaches seem to develop a sense of proprietary right over the student," says track and field coach Frank Haggerty '68. "We really have to guard against it. It's a very natural by-product of recruiting: you worked hard to identify these kids, convinced them to apply to Harvard, then they get in. But once they get here, suppose they want to play another sport, or find something more attractive than athletics? For a coach, it's hard not to be frustrated. You don't own them."

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()