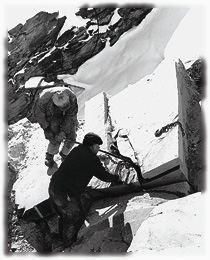

Quarrying slate from Pawlet, Vermont, circa 1970. NEIL RAPPAPORT/SLATE VALLEY MUSEUM, GRANVILLE, N.Y. |

|

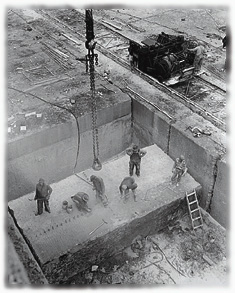

Limestone from Indiana in the nineteenth century.INDIANA LIMESTONE INSTITUTE, BEDFORD, IND.

Limestone from Indiana in the nineteenth century.INDIANA LIMESTONE INSTITUTE, BEDFORD, IND. |

|

Brownstone from East Longmeadow, Massachusetts, in 1901. EAST LONGMEADOW HISTORICAL COMMISSION

Brownstone from East Longmeadow, Massachusetts, in 1901. EAST LONGMEADOW HISTORICAL COMMISSION |

|

In contrast to this crumbling structure, Charles Bulfinch's University Hall (1815) rises solidly across the Yard in massive blocks of Chelmsford Granite. Magma cooling deep within the Earth formed this rock roughly 400 million years ago. The granite's light color indicates that it is rich in aluminum and silica; a darker rock would have more iron and manganese. Small, dark red garnets are embedded in the matrix of light brown feldspar and whitish quartz. On a clear day, shiny sheets of mica wink in the sunlight.

Bulfinch, A.B. 1781, is often credited with helping to start Boston's early-nineteenth-century granite building boom. His desire in 1802 to use granite for a new prison in Charlestown inadvertently led to the introduction of an improved method for cutting stone. Until then, stonecutters rarely quarried rock; instead they worked with loose boulders, using heat to crack the stone. They built a fire on top of a large stone and then dropped a heavy iron ball to split it. Stonemasons would further break the heated rock with sledges. To create square pieces, they cut a groove into the surface with a sharp-edged tool called an axhammer and then struck the rock with a heavy hammer until it fractured.

Bulfinch wanted granite for the prison, but local stone prices were too high. Lieutenant governor Edward H. Robbins, A.B. 1775, one of the prison's commissioners, set out to locate cheaper materials. While passing through Salem, he noticed a building made of rock that had been cut in a manner new to him. After several inquiries he found a Mr. Tarbox of Danvers, who explained his method of drilling a row of holes into the rock and then pounding small wedges into the openings to split it open, creating a smooth face. Robbins was so impressed that he hired Tarbox to instruct the local stonecutters, who were so elated with this new method that "they adjourned to Newcomb's Hotel, where they partook of a sumptuous repast," according to William Sullivan Pattee in A History of Old Braintree and Quincy. This new technique dropped the price of cut stone 60 percent.

Many of the Charlestown prisoners eventually had the opportunity to practice the Tarbox method; three, certainly, of Bulfinch's post-1802 buildings used rock trimmed to size at the prison. The chances are that the stones of University Hall also were cut by prison inmates.

Sunlight bounces off flat flecks of mica in the Chelmsford Granite (bottom) of University Hall (top). The slow cooling of the magma gave the mica time to grow; some magma solidifies so slowly that books of mica several feet thick can form. UNIVERSITY HALL IN WINTER BY PETER JONES

Sunlight bounces off flat flecks of mica in the Chelmsford Granite (bottom) of University Hall (top). The slow cooling of the magma gave the mica time to grow; some magma solidifies so slowly that books of mica several feet thick can form. UNIVERSITY HALL IN WINTER BY PETER JONES |

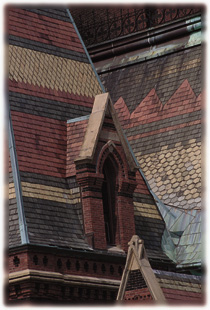

Brownstone, granite, and slate were the triumvirate of common Boston building stones in the 1800s. Harvard's premier slate-roofed structure, Memorial Hall (1878), displays rock from the two most important slate-producing regions of New England. The red shingles came from quarries near Granville, New York, the green shingles from nearby Fair Haven, Vermont, and the black from Monson, Maine. They are also some of the oldest rocks on campus, ranging in age from the pea-soup-green, 550-million-year-old Mettawee Slate, through the red Indian River Slate, to the black Monson, a 400-million-year-old unit, known to geologists as the Carrabassett Formation.

The amount of oxygen and the type of sediment in the depositional environment determined the colors of the Memorial Hall roofing slate. The red in the Granville slate resulted from the erosion of iron-rich soils that were exposed to an oxygen-rich environment. Granville has the only red slate quarries in the United States. If the iron oxides were deposited in an anaerobic environment, they produced a green- to purple-colored sediment. The black slate also formed in an oxygen-starved environment, but contains abundant organic matter that imparted its black coloration.

The formation of Memorial Hall's roofing slates started with clay and silt washing off the North American continent into a vast sea, the Iapetus Ocean (Iapetus fathered Atlas, for whom the Atlantic is named). For 150 million years, the Iapetus served as a dumping ground for sediments that sank slowly into the deep waters of the ocean, building up several thousand feet of extremely fine-grained layers of shale.

During the entire depositional history of these sediments, the Iapetus was slowly closing. As the ocean shrank, it transported a volcanic island arc (similar to Japan) that had risen in the middle of the ocean toward a collision with North America. When the arc slammed into the continent, it pushed the marine-deposited Vermont and New York sediments up onto the land, simultaneously burying and folding them. The weight of this mass of land compressed the sedimentary beds, metamorphosing the shale into a slate. The stress of the collision also caused the grains of clay, which is a flat, sheet-like mineral, to align themselves into a rigidly parallel arrangement, like organizing a collapsed house of cards into a tight deck. The Monson slate metamorphosed in a similar process 50 million years later.

Sunlight has faded, but not weakened, the slates of Memorial Hall, put up in the 1870s. Slates varying in color from similar ones around them are replacements. The soaring central tower was clad in patterned slate until 1897, when it acquired clocks and copper sheathing. The tower burned in 1956 and has not been replaced. MEMORIAL HALL IN 1887, HARVARD UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Sunlight has faded, but not weakened, the slates of Memorial Hall, put up in the 1870s. Slates varying in color from similar ones around them are replacements. The soaring central tower was clad in patterned slate until 1897, when it acquired clocks and copper sheathing. The tower burned in 1956 and has not been replaced. MEMORIAL HALL IN 1887, HARVARD UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES |

This alignment of clay minerals, which facilitates the even and clean splitting of slate into distinct layers, has made slate an important roofing material for hundreds of years. The same qualities make it useful for floor tile, billiard tables, and blackboards. Immigrants from Wales played a critical role in establishing the slate industry in America. They were the first to recognize the high quality of the Monson slate deposits in the early 1800s and also helped to expand the quarries in Vermont and New York in the 1850s.

Not all of the original Memorial Hall roofing slate is intact. In two restoration projects during the past 12 years, workers replaced shingles that had broken because people walked on them, especially at the base of the roof, and other shingles that had cracked because of deterioration of their iron fasteners. Overall, though, the slate has proven its durability.

|

![]()