Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

|

As the university became wealthier, it no longer had to rely on local rock. From 1913 through 1915, architect Horace Trumbauer and his chief designer, Julian Francis Abele, oversaw construction of Harvard's great sanctuary of books, Widener Library, using a buff limestone from Indiana quarries for the foundation and columns. Packed with bits and pieces of information, Widener's building blocks house the University's most accessible fossil collection of marine shells.

These fossils occur in blocks of the 330-million-year-old Salem Limestone, a rock unit that formed in a warm, tropical sea. At that time, most of the land mass now known as North America lay south of the equator. Shallow, clear water covered the area that stretches from present-day Nebraska to Pennsylvania. A myriad of organisms swam and crawled about this placid sea. When they died, their bodies settled to the sea floor, over time solidifying into a 90-foot-thick stone menagerie. This homogeneous matrix of corpses formed a rock that cuts cleanly and evenly in all directions.

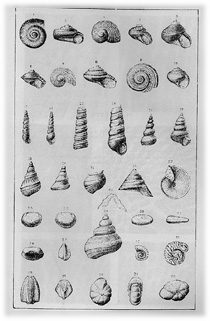

Wave action from long-still tides shattered most of the shells, but many organisms persist and stand out. A unicellular animal known as a foraminifer, which lived in the ooze and muck of the sea floor, is common in this limestone but hard to see, even with magnification. Dotted throughout the walls, and easily discernible, are the poker-chip-shaped stems of crinoids, an extinct relative of starfish, and half-inch-long bryozoans, a sedentary animal that formed colonies of Lilliputian-scaled apartment complexes patterned like Rice Chex cereal. Many shell fragments come from pelecypods, the group that includes oysters, clams, and scallops. A rare find is a perfectly formed half-inch-long snail shell, which resembles a tiny swirled dunce cap.

Salem Limestone is one of the most commonly used building stones in the world. Over the past century, quarries in Indiana have sent this stone to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Empire State Building, Grand Central Station, Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, San Francisco City Hall, and innumerable buildings in cities and towns from coast to coast. Other Harvard buildings that use Salem Limestone include the Gunzburg Center for European Studies (formerly the Busch-Reisinger Museum), Lowell Hall, and Langdell Hall.

Ammonites plied seas worldwide between 400 million and 65 million years ago. The specimen above, a foot across, is preserved in the stone of Hauser Hall. It lived in the outermost chamber of its shell, making new chambers as it grew. Air in the old chambers provided buoyancy, enabling the ammonite to swim. HAUSER HALL, JIM HARRISON

Ammonites plied seas worldwide between 400 million and 65 million years ago. The specimen above, a foot across, is preserved in the stone of Hauser Hall. It lived in the outermost chamber of its shell, making new chambers as it grew. Air in the old chambers provided buoyancy, enabling the ammonite to swim. HAUSER HALL, JIM HARRISON |

William James Hall (1964) on Kirkland Street also incorporates a type of limestone at its base, but one that lacks fossils. Instead of forming at the bottom of a sea, the oatmeal-colored material, known as travertine, precipitates from calcite-rich water often associated with caves or springs. (Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park is a well-known modern travertine deposit.)

The William James panels were quarried from 30-million-year-old deposits near Rome, where travertine has been used since the second century b.c. in buildings such as the Colosseum and Quirinal Palace. Travertine had only a brief period of popularity in Boston, though. As in Harvard Hall's crumbling sandstone, water can permeate the stone's Swiss-cheese-like texture and freeze, expand, and break apart the travertine.

In 1994 Harvard furthered its use of imported rocks with the construction of Hauser Hall. The Law School building's yellow-gray limestone was quarried in Germany. Chosen for its color, the 175-million-year-old limestone contains numerous striking fossil ammonites, an extinct marine relative of the octupus and chambered nautilus, including one specimen that is one foot in diameter.

This modern building tells the story of ancient seas, but also of the changing tastes and fortunes of Harvard. The plain façade and local rock of Harvard Hall has given way to the elaborate patterns and exotic rock of Hauser. Like all good stories, the buildings of the campus can be read for both text and subtext. Natural history and cultural history are linked, and we are reminded that living in an urban environment need not separate us from the natural world.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()