Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

| Books: Not Just for Children | Film: A Voice like Egypt |

| Open Book: An Unorthodox Union | Music: Baroque Diversions |

| Off the Shelf | Chapter & Verse |

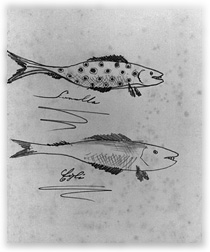

PRIVATE COLLECTION, SWITZERLAND  "The Child is father of the Man": a pencil sketch (above) made by Paul Klee in 1889, when he was 10 years old, and an oil and watercolor painting titled The Goldfish that the artist created in 1925.COLLECTION HAMBURGER KUNSTHALLE |

Modern artists have always sought inspiration from elemental forms. At the time of the French Revolution, Boullée conceived of architecture reminiscent of the Egyptian pyramids, Goethe designed an Altar of Good Fortune comprising a perfect sphere atop a cube, and Flaxman made drawings in the manner of archaic Greek vase painting. Fifty years later, Courbet turned to the popular French prints called images d'Epinal as sources for his Realist paintings of French provincial types (the awkward naiveté of the prints was akin to the critics' caricatures of Courbet's paintings as works made of stick figures, gingerbread men, and children's toys). And 50 years later still, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Seurat took inspiration from the "exotic" arts of Japan, Southeast Asia, and Egypt and their independence from the constraints of Western perspectival systems.

Modern art's embrace of "primitivism," with its willful distortion of forms, could be said to have been a prerequisite for a break with tradition. In this century, Russian Futurists mined the vitality of provincial signboard painting, peasant woodcuts, and carved pastry molds for their independence from conventional modes of depiction, just as the German Blue Rider artists mined Bavarian glass painting, Picasso mined Africa sculpture, Jackson Pollock mined Native American art, and Brice Marden mines Chinese calligraphy. Archaic or "primitive" or culturally distant forms have liberated modern artists from the perceived limitations of their own traditions.

This is not news, of course. As long ago as 1938 Robert Goldwater wrote Primitivism in Modern Painting (later revised and reissued as Primitivism in Modern Art), a book in which he focused on the influence on modern artists of African and Oceanic and even children's art. There he noted that "this affinity of large sections of modern painting to children's art is one of its most striking characteristics," and that children's art was often used by twentieth-century artists "with a particular accent (witty, gay, or brutal) to comment upon man's adult condition." In his view, "primitive" art, including children's drawings, was important to modern artists not simply or even primarily for its formal properties, but for its expressive potential and psychological power as well.

Jonathan Fineberg's recent study, The Innocent Eye: Children's Art and the Modern Artist, picks up on Goldwater's earlier observations and adds significantly to them. He extends the list of examples to include such recent artists as Elizabeth Murray, Francesco Clemente, and David Hockney, and shows that many of our century's greatest artists not only used children's art but collected it, too--in some cases amassing vast quantities of it, and in other cases saving and using their own early drawings or those of their children.

Fineberg is professor of art history in the School of Art and Design of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His book was initiated by a conversation with his former teacher, Rudolf Arnheim, the noted theorist of the psychology of vision and one-time professor of the psychology of art at Harvard. Arnheim had been asked by the Detroit Institute of Arts to organize an exhibition comparing children's art with great works of modern art. Arnheim declined and suggested Fineberg instead. Initially skeptical, Fineberg soon became intrigued and turned first to the art of the early twentieth-century master Wassily Kandinsky, on whom he had written his Harvard dissertation and who was widely known to value children's art. There Fineberg found so many references to a child's style of rendering that he began to suspect that Kandinsky must have collected children's art. With the help of Armin Zweite, then director of the Gabriele Münter Archive at Munich's Lenbachhaus (Kandinsky lived with Münter near Munich at a crucial time in the development of his abstract painting and left many documents with her when he returned to Russia in 1916), Fineberg discovered that Kandinsky did indeed have such a collection. This led him to look for similar collections held by other modern masters, which he found, in one way or another, in the cases of Münter, Picasso, Klee, Miró, Dubuffet, and Asger Jorn.

Kandinsky and Münter began collecting children's drawings and paintings together in 1908 and over the next eight years amassed almost 250 of them. These ranged from simple depictions of animals in profile to more complicated arrangements of stick figures in landscapes. Fineberg cites Kandinsky's reproduction of a drawing by a 13-year-old girl named Lydia Wieber in the Blue Rider Almanac, as well as his and his colleagues' statements about the sincerity and profundity of children's art: August Maacke, for instance, said, "Are not children more creative in drawing directly from the secret of their sensations than the imitator of Greek forms?" All of this leads Fineberg to search for equivalents between the drawings and paintings Kandinsky and Münter collected and Kandinsky's own paintings. He sees a child's rendering of an elephant as "excerpted" and "altered" by Kandinsky in his own Elephant of 1908, and children's drawings of railway steam engines and of a horse and cart as "at the very least exemplary of a class of child renderings that provided prototypes for Kandinsky's handling of the motif[s]...."

This kind of search for equivalents is slippery. The comparisons are never really close enough to be convincing (in Kandinsky's painting, the elephant is turned the opposite way, is thinner with longer tusks, and its trunk is pointing up rather than down; in the case of the steam engines and horse cart, the images are only generically related, if related at all). And Fineberg senses that. He qualifies his observations with such phrases as "seems related to the children's drawings in his collection"; "Kandinsky seems to have been more intent on analyzing and exploiting the general characteristics that made the children's renderings 'childlike'"; and "the ubiquitous, stiff, cruciform figures, as in Sketch for Composition II, also seem to derive from child art in the Kandinsky-Münter collection" (the italics are mine). And when he can't relate images and their descriptive vocabulary more closely than this, he finds relations in their similar use of space, the way children's art and Kandinsky's paintings, for example, each "annihilated the smooth transitions of space from foreground to background, isolating the images from one another."

|

Fineberg need not have tried to make these connections at all. It is sufficient that he identified the existence of the Kandinsky-Münter collection of children's drawings and paintings and noted Kandinsky's documented high regard for children's (and other forms of "primitive") art and the license they gave him to make paintings independent of received notions of depiction and composition. But of course, only the evidence of the collection is really new information. Goldwater had already cited Kandinsky's comments in the Blue Rider Almanac that "[t]here is an enormous, unconscious strength in children, which here expresses itself, and which places the work of children on as high (and often on a higher) a level as that of adults." (I should point out that Fineberg acknowledges Goldwater's work in his preface but gives its most recent publication date, 1986, rather than the original date, 1938, and gives Goldwater's book the title of William Rubin's 1984 Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalog, Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art.) Apparently Fineberg wanted to correct Goldwater's assertion that "none of [Kandinsky's] work so far examined has involved a pervasive influence of the child's method of representing his thoughts and his experiences...." And that he does, in spades, even without having to draw close connections between specific paintings by Kandinsky and certain examples of children's art.

fineberg does this also with paul klee. But there the task is much easier. Goldwater had already stated that "it is first in the pictures of Paul Klee...that we are given a chance to examine paintings in which the art of the child is the predominant influence." Here Fineberg does not have to convince us of the influence of children's art on the modern artist, but only give us a sense of the extent of that influence. We see it in Klee's charming and witty stick figures, manipulation of spatial recession, and--perhaps most interesting--in his use of various children's graphic techniques. There are the simple graphite and colored pencil drawings; the "magic" paintings in which colors are laid down first, then covered with black, and the image made by scratching through the black surface and letting the color shine through; and, most of all, the free use of bright and vibrant watercolor. Klee was childlike in the way he delighted in making art and in discovering its magic. He was, of course, very sophisticated in the way he commanded his media, but the result is almost always fresh and surprising, as children's art often is. His work rarely seems as labored or self-conscious as Kandinsky's does.

This is equally true in the case of Dubuffet. His paintings seem more childish than child-like, genuinely naive and unselfconscious. Fineberg acknowledges this and quotes from Dubuffet's own remarks about his intentions:

"I have always tried to represent any object, transcribing it in a most summary manner, hardly descriptive at all, very far removed from the actual objective measurements of things, making many people speak of children's drawings. Indeed, my persistent curiosity about children's drawings, and those of anyone who has never learned to draw, is due to my hope of finding in them a method of reinstating objects derived, not from some false position of the eyes arbitrarily focused on them, but from a whole compass of unconscious glances, of finding those involuntary traces inscribed in the memory of every ordinary human being, and the affective reactions that link each individual to the things that surround him and happen to catch his eye."

Fineberg then goes on, in detail and convincingly, to show how Dubuffet used the vocabulary and effects of children's drawings from his collection to advantage in his own paintings and watercolors. As with Klee, and unlike Kandinsky, Dubuffet's naive style seems "natural," and thus Fineberg's comparisons are on the whole convincing.

But I am not as convinced of Fineberg's claims about more recent artists, such as Mark Rothko, Elizabeth Murray, and Joel Shapiro, whom he links together all too hurriedly at the end of his book with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Julian Schnabel, A.R. Penk, Joseph Beuys, Alice Aycock, Jasper Johns, and numerous others. Here the references to children's art are too general and fleeting to be convincing. No recent artist is given the same close scrutiny as Kandinsky, Klee, Dubuffet, and Picasso receive in the preceding chapters. Perhaps Fineberg should have limited his concern to one period or the other: to the first decades of this century and the formation of abstraction, or the decades since World War II and the resurgence of expressive figuration. As it stands, sadly, Fineberg rushes to a conclusion after having spent chapters establishing his thesis carefully and thoughtfully. To conclude with only a couple of paragraphs on Jasper Johns is disappointing, after pages and pages on Kandinsky and Klee.

I do not mean by these criticisms to detract from the most important contribution of Fineberg's book, which is the way he weaves together evidence of modern artists collecting children's art, remarking upon it, using it in their work, and, in some cases, physically integrating it into their own (as when Picasso and his children, Paloma and Claude, drew on the same sheet and signed it in 1953). This is all new material, and very important to our still developing sense of the role nontraditional art forms played in the working out of modern art. With Fineberg's book, we can add children's art to the arts of Africa, Asia, Oceania, provincial Europe, the insane and unschooled, and popular commercial culture, as crucial influences on modern Western art and artists.