Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

| Books: Not Just for Children | Film: A Voice like Egypt |

| Open Book: An Unorthodox Union | Music: Baroque Diversions |

| Off the Shelf | Chapter & Verse |

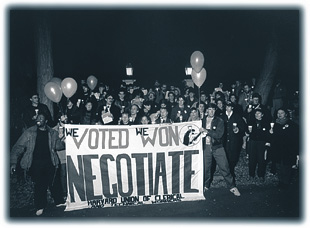

Workers voted to accept the union in the spring of 1988. Harvard took evasive action. In the fall, union members demonstrated outside the home of President Derek Bok, demanding that Harvard begin contract negotiations.RICK STAFFORD |

We Can't Eat Prestige: The Women Who Organized Harvard, by John Hoerr (Temple University Press, $29.95), is a narrative of the 15-year effort of a group, mostly women, to unionize Harvard's 3,600-member "support staff," mostly women. Hoerr encountered obstacles to his research. "With a few exceptions confined to 1992 and early 1993, current Harvard officials refused to be interviewed," he writes. "The old belief among employers that a union plays only an adversary role in the institution, and that journalists and writers of labor history have no object but to dramatize conflict, is still current in the Harvard administration." In this excerpt, he begins by quoting the union's prime organizer and longtime leader, Kris Rondeau.

"People with ideas are welcome here. We take the position that anything is possible and anything is negotiable. We want our members to see themselves as being players in the world." Later she expanded on this idea, quoting the first sentence from her favorite novel, David Copperfield. "'Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.'" ...

The Harvard union style incorporates many elements; it is romantic but hard-headed, reform-minded, garrulous with a broad satirical edge, often comic--in a word, Dickensian, though in a female way. If this was not a wholly new kind of unionism, it was certainly unusual in the United States....

In the world of work, there is no more precious thing than a collaborative effort in which groups of people overcome adversarial instincts in order to work together. When Derek Bok in 1988 finally agreed to bargain with the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers, he intended to do much more than set down rules to govern a bureaucratic relationship. He intended, he later said, "to forge some kind of new relationship...to try to do something that will be as creative in this area [labor relations] as Harvard tries to be in all it does."

By the beginning of 1997, much of the creativity had been throttled and the "new relationship" that Bok envisioned existed in outline only. Lacking a continuing vision and a guiding intelligence, the many-headed management of Harvard had reduced the relationship to a fragile thing gasping for air. This deterioration was reflected in the written labor agreement. Once a thin document containing a philosophy of participation and a few general principles, it had grown thicker with Latinate legal terms. Seventeen "memoranda of agreement" covering specific practices were included in the 1995 contract. Lamented [union director] Bill Jaeger, "We're drifting toward rule-making."

HUCTW leaders still thought it possible to win a participatory role in the university without compromising their ability to fight for members' economic interest. "We have a vibrant union that can take care of itself," Rondeau concluded, "but we've been unsuccessful in finding partners in a decentralized university. It would be better if people at the top embraced these [participatory] concepts, but whether they do or don't, there is still a lot of room for growth, and we won't stop trying."

In the meantime, the union had accomplished quite a lot. It had created a community where none existed. It had advanced the economic well-being of many thousands of employees, union and nonunion alike. By organizing the creative energies of its members, HUCTW had improved the university in countless, immeasurable ways that administrators and faculty could not have managed alone. What remained to be done was something that women in particular and workers in general had been struggling to achieve for more than a hundred years: gaining influence in decision making. With perseverance, that too might come.