Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

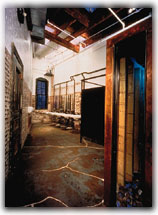

A 1930s Paris theater integrates lighting and electric ventilation systems with the balcony surface. HENRI BELOC

A 1930s Paris theater integrates lighting and electric ventilation systems with the balcony surface. HENRI BELOC |

FUNCTIONS FIND FORM

The word "infrastructure" owes its origin to the Maginot Line, France's massive post-World War I complex of military fortifications. "The tunnels, bridges, and outcroppings that formed the front were connected as an imaginative projection the French called 'infrastructure,'" says associate professor of architecture Sheila Kennedy, M.Arch. '84. The term has evolved to signify all the functional systems that permeate our built environment--sewers and water mains; electric, telephone, cable television, and data lines; heating systems, gas conduits--everything from copper pipes to fiber-optic cable.

Kennedy's 1994 Public Bathrooms Project makes the chase wall into a vitrine. BRUCE T. MARTIN

Kennedy's 1994 Public Bathrooms Project makes the chase wall into a vitrine. BRUCE T. MARTIN |

Modern architects have subordinated infrastructure to structure--even though the former often accounts for 30 to 35 percent of the cost of new construction. Even in industrial design, "we tend not to see the thing that actually produces the effect," says Kennedy, noting that the Tizio lamp, a low-voltage halogen light of the 1980s, was advertised to look as if it had no wire when placed on an executive's desk. "The culture wants the end product--light--but we do not care about the system of distribution," she says. "In fact, we don't even want to see it."

A turn-of-the-century Italian advertisement portrays electricity as a magical fairy goddess. COURTESY SHEILA KENNEDY

A turn-of-the-century Italian advertisement portrays electricity as a magical fairy goddess. COURTESY SHEILA KENNEDY |

This is problematic for architecture because infrastructure is becoming denser as technology evolves. In 1800, water pipes for a building would have been unusual; today, heating, plumbing, and electricity are being joined by data ports, fiber-optic and television cables, and satellite dishes. "The universe of infrastructure is rapidly expanding and penetrating every single surface of the building," Kennedy says. Adding to the problem is the fact that structural and infrastructural priorities compete. "They are often fighting for the same space," Kennedy notes, observing that "architects don't want a mechanical ventilation duct in the same place as a column."

Kennedy's response to this, as a researcher and teacher at the Graduate School of Design and as a principal of the Boston architecture firm of Kennedy & Violich, is to design infrastructures into the very architectural surfaces that contain them. Try as we may to conceal these functional elements, she says, "They will out": in order to provide heat, water, light, or data, their conduits must somehow surface. But perhaps they can be the surface--as in designs for radiant heating that Kennedy is developing with Runtal North America Inc., a manufacturer of hydronic heating systems that underwrites some of her research, and its Swiss parent firm. "Instead of a discrete radiator in the corner of a room, think of a whole wall with hot water running through it--the wall itself begins to radiate heat," she explains. "The radiant source could also be the mullion of a window, a banister on a stairway--or a radiant floor, with tubes of water running through it."

Newly emerging "smart materials" that include ceramics, plastics, and glass may eventually let us run electricity through wall claddings rather than wires. Smart picture windows can darken to reduce incoming light on hot days, then clear up after dark. Smart-glass windshields in jet cockpits may display a map on the glass itself, helping pilots to navigate and land.

Just as infrastructure influences the form of buildings, it can also shape social relationships. Kennedy asks us to compare a room lit by several widely spaced incandescent lamps to one with a luminous ceiling that illuminates the entire space evenly. The latter option "is a more democratic distribution of light," she says. "Infrastructure has functional, spatial, and organizational effects on how an institution works."

To implement these ideas, Kennedy and her colleagues collaborate with mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, and communications and data engineers early in the design process. All of these professionals produce their own sets of drawings for a prospective building. But "the architect does not have control of these territories," Kennedy says. Instead of bemoaning that fact, she works to incorporate those infrastructural elements in her design--as in a current project involving sidewalks, streets, pedestrian walkways, and artificial illumination in a design for Boston's theater district. "We can no longer afford to hold infrastructure as a separate category," Kennedy says. "It's too culturally significant--and too pervasive."

~ Craig Lambert