Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

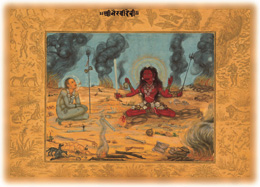

An Indian painting from the Mughal Period depicts Shri Bhairavi Devi, a red-skinned, multi-armed goddess who wields a sword and scepter; skulls, skeletons, blood, smoke, and fire surround her. Such mythic-religious figures symbolize human anxieties about nature, chaos, and the unknown. The Goddess Bhairavi, attributable to Payag, Mughal, circa 1630-35, courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, private collection

An Indian painting from the Mughal Period depicts Shri Bhairavi Devi, a red-skinned, multi-armed goddess who wields a sword and scepter; skulls, skeletons, blood, smoke, and fire surround her. Such mythic-religious figures symbolize human anxieties about nature, chaos, and the unknown. The Goddess Bhairavi, attributable to Payag, Mughal, circa 1630-35, courtesy of the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, private collection |

In the preface to his forthcoming book, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, associate professor of psychology Jordan B. Peterson does a rare thing in an academic text. Titled "Descensus Ad Inferos," the preface recounts the author's descent into a personal hell; it is an intellectual autobiography of sorts, describing the anguish that brought him perilously close to madness. The question "How did evil--particularly group-fostered evil--come to play its role in the world?" obsessed Peterson; his scholarly odyssey eventuated in a sweeping theory of narrative, belief, meaning, and religion.

In the process, he takes up poetry and brain chemistry, psychology and history, religion and animal behavior; the book's bibliography ranges through existentialist philosophers and literary critics, as well as Dante, Dostoevsky, Goethe, Stephen Hawking, C. G. Jung, Lao Tzu, Konrad Lorenz, brain scientist A.R. Luria, Milton, Nietzsche, Piaget, Solzhenitsyn, Voltaire, and Wittgenstein. Maps of Meaning, which took 13 years to write and which Routledge will publish next spring, is a grand, sprawling, ambitious undertaking, an intellectual adventure that aims to synthesize disparate knowledge in the classic, old-fashioned tradition of social science.

Working from his background in neuropsychology and brain chemistry, Peterson asserts that there are two distinct functional systems in the human brain: one to "handle things we understand--the domain of order and culture; and another to cope with things we don't understand--unexplored realms, nature, chaos." He writes of the relationship between them: "Something we cannot see protects us from something we do not understand. The thing we cannot see is culture, in its intrapsychic or internal manifestation. The thing we do not understand is the chaos that gave rise to culture. If the structure of culture is disrupted, unwittingly, chaos returns. We will do anything--anything--to defend ourselves against that return."

Human beings are territorial, but, Peterson says, "because people are capable of abstraction, the territories we defend can become abstract. Belief systems--the familiar 'abstract territories' we inhabit--literally regulate our emotions." When a threat arises to a key belief, the emotional consequences can be devastating. Pathological attempts to stave off internal chaos may manifest themselves as shocking realities like the Gulag, Auschwitz, or the Rwanda massacres. "People generally prefer war to be something external, rather than internal," Peterson explains. "We believe that crushing the enemy will prove easier than re-forming our challenged beliefs."

Luckily, there is a third factor: the principle that mediates between chaos and order, which Peterson calls logos, exploratory consciousness. While the a priori response to the unknown is generally fear, the second response is curiosity and exploration. Heroic figures are those who mediate between the two realms, bringing the unexplored into the domain of culture, or, perhaps, destabilizing an overly rigid society. "Solzhenitsyn said that one man who stopped lying could bring down a tyranny," Peterson says. "I don't think he meant that as a metaphor--or hyperbole."

~ Craig Lambert