Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

When Henry David Thoreau, A.B. 1837, went to live in the woods, he had to hunt to find some. He built his hut in one of the few forest areas remaining in Concord. Agrarian zeal had turned much of Massachusetts into an "open, vibrant, and quite domesticated" scene, writes David R. Foster, director of the Harvard Forest, in Thoreau's Country: Journey through a Transformed Landscape (Harvard University Press, $27.95). In the end, New England farmers couldn't compete with greener pastures in the Middle West and in the mid-nineteenth century began to abandon their fields. Thoreau's journals are full of observations of the process through which rolling farmland began to transmute into the relative wilderness we inhabit today.

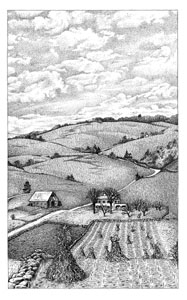

ABIGAIL RORER, FROM THOREAU'S COUNTRY

ABIGAIL RORER, FROM THOREAU'S COUNTRY |

Thoreau's writing illuminates the important first stages of land abandonment. The process was not abrupt and wholesale, but gradual, inadvertent, and pulselike. Tilled field went to pasture, where it supported scraggly livestock as the pasture then went to shrubland and finally to forest. A struggle often ensued. Cows would continue to graze the grasses as the pines invaded the pastures. The farmer, though committing less and less effort to farming, would periodically beat back the pines with a bushwhack, scythe, or axe in order to maintain some grazing land for his dwindling herd. But eventually the new trees would overtop and crowd out the cows to win the battle. The farmer, sensing the futility and inevitability of the process, would drive the cattle out and would reluctantly accept his role as owner of a new woodlot.

From some of the details of Thoreau's writings we learn much about the processes that shaped the forests as they invaded the abandoned fields and came to dominate our landscape. For example, Thoreau's observation that the farmer's custom was to abandon land gradually and to let pines and cows coexist in pastures is significant. Although pines have many natural features that enable them to establish and grow in open grassy areas, such as small, easily dispersed seeds, tolerance for drought under full sunlight, and the ability to compete with dense grass sod, one additional advantage that they hold over hardwoods such as birch and maple is that both white and pitch pine are less palatable to grazing animals. Thus the practice of allowing cattle to continue grazing fields as they went into disuse and became forests may have been an important factor contributing to the prevalence of pitch pine and white pine on old fields, the development of the New England landscape into a region of pine forest, and the subsequent era of pine logging. As Thoreau correctly stated, social change and land abandonment resulted in a peculiarly New England mode of developing a woodlot.