Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

Air Zamboni |

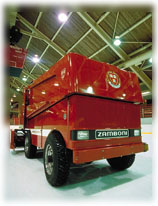

"There are three things people love to stare at," according to cartoonist Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts. "A rippling stream, a crackling fire, and the Zamboni going around and around on the ice." That paean, from the forthcoming book Zamboni by Theresa Loong '94, celebrates one of the most fascinating sideshows in sports. Between periods of an ice-hockey game, when the ice-resurfacing machine--commonly called a Zamboni, after the leading brand--tours the rink, enraptured fans do indeed stare as the driver cuts overlapping oval swaths on the ice. The machine, which can reach speeds of up to 9 miles per hour, scrapes off a skate-scarred, slushy epidermis, washes the ice, and deposits a fresh layer of water that freezes to a smooth glassy surface. The ritual very nearly embodies a myth of renewal.

Yet the beloved Zamboni may pose hazards. Research by Jonathan Levy '93, a doctoral candidate at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH), indicates that the exhaust from ice resurfacers can generate unacceptably high levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) in the air. "It's like running your car inside a closed garage," says Levy, who, although not a hockey player himself, is a skater who never missed a home hockey game in college. "A lot of rinks are old and don't have good outside ventilation. Besides, too much ventilation leads to high energy bills and problems with ice quality." The acute effects of exposure to NO2 include bronchitis, chronic cough, and exacerbation of asthma; chronic exposure may lead to infections of the lower respiratory system in children and lower respiratory symptoms (like bronchitis) in adults. And a folk term, "hockey lung," refers to the chronic cough of some rink personnel. "There's cause for concern because a lot of children skate in rinks five to seven days a week," says Levy, "and because they're exercising, they are breathing harder, taking in cold air."

During three recent winters, Levy and three HSPH faculty members studied air quality at 19 Boston-area public rinks. The researchers assessed NO2 levels with one-inch-square badges (nicknamed "Yanagisawa badges" after their inventor, adjunct professor of environmental health Yukio Yanagisawa, one of the study's coauthors) that can be clipped to clothing or the side of a rink. The badges contain a series of filters; a chemical coating on one layer changes color upon contact with nitrogen dioxide, growing darker with greater exposure. Results from 647 measurements showed mean levels of NO2 that were often above the World Health Organization (WHO) standard of a maximum of 110 parts per billion (ppb). Fifty-seven percent of samples from rinks with propane-powered Zambonis exceeded the WHO standard (registering a mean level of 206 ppb), as did 40 percent of those from rinks using gasoline-powered resurfacers (registering a mean of 132 ppb); electric resurfacers, which do not emit combustion fumes, produced lower levels (a mean of 37 ppb).

Electric-powered resurfacers can cost up to $100,000 (large internal-combustion models run around $60,000) and only about 3 percent of rinks worldwide currently use them. But they are becoming more prevalent: although only one of the 19 rinks studied had an electric resurfacer in 1994, three years later, eight had them. Improved ventilation is another remedy, and retrofitting propane- and petroleum-burning machines with three-way catalytic converters, says Levy, is also effective: "Some good research has shown that this can handle the problem quite nicely."

~ Craig Lambert