Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

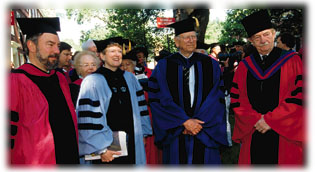

Reading the RegaliaA guide to deciphering the academic dress codeby Cynthia W. Rossano Gowns of Harvard crimson flank the pale blue of Columbia and the royal blue of Yale. The velvet bands on the sleeves mark doctoral rank. The tall hat (right) is from the University of Sussex. |

Hats off to John Harvard! As the Commencement procession winds through the Yard by his statue at the west front of University Hall, he receives the doffed-hat salute of his beneficiaries in the passing parade. What a parade it is! With academic costumes representing both national and international universities, the line of marchers is ablaze in color. Brilliant scarlets from Cambridge and Oxford catch the eye, snatches of fur on gowns from foreign universities lend a soft touch, visions in blue lace and fringes pass by, and even the more subdued black robes of Harvard seniors are brightly decorated with colorful crow's-feet.

What does this glorious display of caps, gowns, and hoods mean? How is the regalia chosen? Does a scholar rise on Commencement morning and decide, "Today I will wear the black mortarboard with a gold tassel, the red gown, and the purple hood?" Is there a universal system that governs the wearing of academic costume? A way to interpret it?

Help is at hand from the dress code established in 1897 by the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume, and followed by most American universities since 1902. Using the code, and armed with a measuring tape and a keen awareness of color, the fledgling reader of regalia may easily become a connoisseur.

"Candidates for the first degree"--bachelor of arts or sciences--wear simple black gowns bearing white crow's-feet emblems, unique to Harvard, on the lapels. |

The origin of academic dress dates from the earliest days of the oldest universities. When those long-ago centers of learning were taking form during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, they were under the jurisdiction of the Catholic church, and the first true scholars were clerics, members of the literate class. Their careers, their teaching, studying--their entire lives--were conducted in the underheated buildings of medieval times, and their clerical robes were needed as much for warmth as for distinction. These scholars wore heavy brown or black cloaks, cut in a circle, with a hole for the wearer's head; and to further shield themselves from long, cold European winters, they frequently added layers of hoods and capes. In some areas during the Middle Ages the hood was an alms bag slung around the necks of begging friars; in others, the medieval cowl was worn simply for warmth, drawn tightly around the face by the liripipe. Women and men of all classes adopted similar dress as protection from drafty and damp conditions. As heating improved, the outer robes became less bulky.

Today's academic gown, which at Harvard is made of materials ranging from cotton to silk, almost certainly descends from the inner robe or tunic, with the velvet facing on today's doctoral robes reminiscent of the way the ancient linings looked when robes fell open. The present academic hood stems from the medieval cowl, as does the tippet worn by the masters of the Harvard Houses, and the liripipe that remains as an appendage at the bottom of the hood. The academic cap, or mortarboard, is grandchild of the skullcap worn by tonsured clerics.

|

From such simple beginnings our present system of academic caps, gowns, and hoods has evolved.

Academic institutions in Europe and other countries abroad continue to accept a wide variation of color and style in formal costume. Much academic dress reflects imaginative ethnic design and materials. One university has as its regalia a navy blue damask robe with decorations in gold and silver, and sleeves in lime green silk; another chooses a black silk robe heavily trimmed with gold lace and ornamentation.

The American approach has been a little less flamboyant. At Harvard, academic fashion had been traditionally restrained, although flashes of color have always brightened the Commencement scene. In Three Centuries of Harvard, historian Samuel Eliot Morison refers to a description of a colonial Commencement: "The sober academic colors were relieved by occasional gold-laced hats and coats, by a sprinkling of His Majesty's uniform, and by the score of silver shoe-buckles which glistened in the sun with every footstep, to the delight of the public and of the wearers of them."

Topping things off at left, an honorand's cap from the University of Ancona, Italy; at right, a Nigerian cap with Cambridge doctor's gown. |

In the late 1800s, American colleges and universities adopted a code of academic dress that everyone could immediately recognize and follow. Harvard did not participate in the first meeting called to consider such a scheme; but at the quincentenary of the University of Heidelberg in 1886, and again at the 250th anniversary of Harvard in that same year, the kaleidoscope of color in the European hoods and gowns elicited warm interest from within the Harvard community.

The next step toward Harvard's adoption of regalia came in 1897, when a committee was appointed under a vote of the Harvard Corporation "to prepare a scheme of gowns, caps, and hoods to be submitted to this Board." Five years later a letter sent by the University marshal, Morris Hicky Morgan, to President Eliot enclosed a "Scheme for academic costume expressed in a few words, and covering all that ...it would be necessary for us to adopt here."

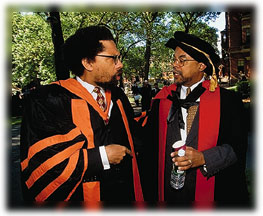

A Princeton doctoral gown burns bright next to a doctoral robe from the University of Cambridge. Note the distinctive British version of the mortarboard. |

The scheme Morgan referred to had been drawn up by the nonprofit and voluntary Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume, which was formed with the intention of creating academic regalia specifically designed for each member of the academic community, as a reminder of the continuity and dignity of learning. The firm of Cotrell and Leonard Inc. (now a division of E.R. Moore Company), sole depository for the bureau, published a pamphlet that described the advantages of having an intelligible system of caps, gowns, and hoods, and explained that the scheme would "subdue the differences in dress arising from different tastes, fashions, and degrees of wealth." General acceptance took about five years.

The system is simple. Bachelors' and masters' caps, most often mortarboards, sport long black tassels, while the doctoral tassel may be of gold. Harvard presidents are entitled to gold tassels, though no rule requires it. Neither is there a rule governing whether the tassels should hang to the right or to the left of the mortarboard. Some colleges have created a tradition of wearing the tassel on one side before graduation and switching it to the other after the degree is conferred, but as a regalia expert at Cotrell and Leonard wryly observed in the June 1984 Harvard University Gazette, "a gust of wind could change your academic standing in a moment."

The pale blue, black, and gold hood over the doctor's gown marks a master's of education from Bank Street College. |

Three types of gowns and three types of hoods are designed for bachelors, masters, and doctors respectively. The bachelor's gown has long pointed sleeves; the master's gown has long sleeves ending in curved pouches that hang to well below the knee; the doctor's gown, crimson at Harvard since 1955, is like a pulpit or judge's gown, faced with velvet, and with three velvet bars on full round open sleeves.

A note on the use of crimson as Harvard's color. In 1858, to distinguish themselves from other entries in a Boston City Regatta, six Harvard crew members tied brilliant crimson bandannas around their foreheads. When they won the race, crimson became Harvard's rowing color, and in time was adopted by other teams. One of the original crimson handkerchiefs is preserved in the University Archives, and Morison notes, "in 1910 its color, officially described as that of arterial blood, was formally adopted by the Corporation as the official livery color of the University."

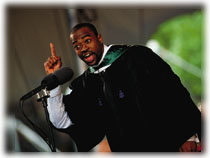

Purple crow's-feet and black sleeve bands mark a Harvard Law School J.D.; the green hood edged with white, a Dartmouth B.A. |

Every Harvard academic gown has an embroidered crow's-foot near the yoke on each of the facings, double for earned degrees and triple for honorary. The color of the crow's-foot designates the faculty conferring the degree.

The use of the crow's-foot emblem is unique to Harvard. The story of how it came about is described in a letter written by Morison in 1936. Professor Eugene Wambaugh, as a member of Eliot's committee on academic dress, had been asked to see that the proposed gowns be given some distinctive Harvard feature. Morison writes: "The committee decided that all Harvard hoods should be lined with crimson; and Dr. Wambaugh, who had been reading up Harvard history, had heard of crow's-feet adopted for undergraduates' dress in 1822."

"One Cambridge gentleman," continues Morison, "produced a jacket worn by his grandfather, and an old grad sketched the crow's-feet from memory. Both agreed, and double crow's-feet in different colors, to represent the different faculties, were recommended in the committee report for the lapels of Harvard gowns. The report was at first 'laid on the table' by the Corporation, President Eliot being much against caps and gowns, but was finally adopted in 1902."

Of the various colors chosen to mark the different degrees, some derive from the Middle Ages and have easily remembered historic connotations. White for the bachelors of arts and sciences comes from the white of the Oxford and Cambridge B.A. hoods; dark blue for the doctor of philosophy is the color of truth and wisdom; medium gray has long represented business; lilac, dental medicine; and yellow, design. The scarlet for divinity follows the traditional color of the Christian church and crucifixion; light blue for education is again the color of truth and wisdom, as is the peacock blue for government. Purple for law is reminiscent of bygone kings who made the laws; salmon pink signifies public health; and the green for medicine is the green of medicinal herbs.

Masters of Harvard Houses wear tippets, like the one at right, embroidered with the House shield--in this case, Lowell. |

Rainbow-hued crow's-feet and golden tassels notwithstanding, it is the hood above all that has the greatest degree of color and symbolism. Its silk lining is in the colors of the university conferring the degree; a border, often of velvet and sometimes of different widths for the different ranks, may signify which faculty conferred the degree. Harvard bachelors do not receive hoods; all masters' and doctors' hoods are black on the outside and lined in crimson. They are distinguished by length only--this is where the tape measure comes in--with three and one-half feet allowed for masters, and four feet for doctors.

Regalia readers will glimpse snippets of other hoods at Commencement: perhaps those of Yale, with a blue lining; Princeton, with a lining of orange and black chevron; Dartmouth, lined with green; and Wellesley, with dark blue. Columbia's light blue lining is crossed by a white chevron; a North Carolina hood that uses the same light blue as Columbia is differentiated by having two white chevrons.

Several hundred colleges and universities are registered with the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume: each institution is unique under the system, with its own colors or color combinations.

Doctoral robes from Stanford (left and center) are paired with hoods that indicate higher degrees in education and health. The grand gown at right, alas, remains a puzzlement. |

Every so often a committee formed by the American Council on Education is asked to decide whether the code of academic costume should be revised. With the exception of a few alterations and additions, no significant changes have been recommended: the assortment of academic caps, gowns, and hoods at Commencement today would not be unfamiliar to a scholar suddenly appearing from the Middle Ages, dazzled though he might be by its vivid diversity.

But what about rules for academic dress before the founding of the Intercollegiate Bureau? Did everyone on Commencement day dress as the spirit moved?

"The early statutes of Harvard College were few and meagre," reports Morison in his History of Harvard University. Writing about colonial times in Three Centuries of Harvard, he observes, "The general use of academic gowns came in during this century. A graduate in 1712 offered to outfit the members of the College with gowns, but apparently nothing was done about it at the time." He refers to Burgis's Prospect of the Colledges of 1726 that shows figures stalking about the Yard in loose, trailing gowns; "but," he writes, "he may merely have been copying Loggan's pictures of Oxford and Cambridge Colleges." Morison goes on to say, "In 1773, on the occasion of a classmate's funeral at Boston, the freshmen were allowed to wear 'Black Gowns and Square Hats' and 'seemed very grand' as they 'walked about the Town with their Black Gowns on, the Inhabitants not knowing what it me[a]nt nor who they were.'"

An entry from the Laws of Harvard College of 1807 enlightens us as to proper early-nineteenth-century decorum: "Every Candidate for either Degree shall attend the public procession, on Commencement Day, to and from the College. And every Candidate for a first degree shall be clothed in a black gown, or in a coat of blue grey, a dark blue, or a black color; and no one shall wear any silk nightgown, on said day, nor any gold or silver lace, cord, or edging upon his hat, waistcoat, or any other part of his clothing, in the College, or town of Cambridge. And any Candidate for his Degree, who shall neglect such attendance, without sufficient reason, to be allowed by the President, or shall be habited contrary to this regulation, shall not be admitted to his Degree that year." The dress code, clearly, was serious business in 1807.

Andrew Preston Peabody, D.D., preacher to the University and Plummer professor of Christian morals emeritus, in his Harvard Reminiscences of 1888, remembered the gowns of 60 years earlier as costing "two or three dollars" to rent and being "of the flimsiest texture and of scanty amplitude." Yet within 10 years of the publication of Peabody's reminiscences, members of the first Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume would set the standard for American academic dress that we know now.

Multicolored hoods, gowns, and crow's-feet. The Yard is bright with the rich and varied display of academic costume, and scholars on Commencement morning know exactly what glorious regalia to don, and to precisely what lengths they may go. So, hats off to you, John Harvard! The passing parade bows to your role in this brilliant pageant, saluting you as it marches on.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()