![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

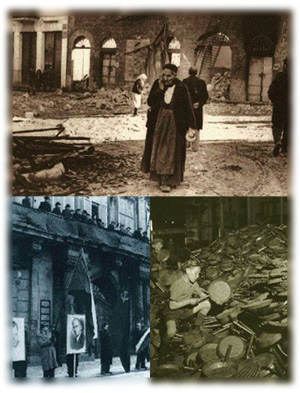

| Gains and losses in Europe: A Greek peasant walks through the ruins of a town recaptured from guerrilla forces; Communist demonstrators in Prague; a boy in Düsseldorf inspects frying pans made from recycled weapons.CLOCKWISE FROM TOP: AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS; © ARCHIVE PHOTOS; AP/WIDE WORLD PHOTOS |

When Secretary of State George C. Marshall delivered his lapidary Commencement address under the Harvard elms on June 5, 1947, the concept he outlined was hardly a finished "plan." Still, it summarized weeks of intensive discussion and position papers at the State Department and other government agencies.

Political and economic developments seemed grave for many reasons. Marshall had returned dismayed from the Moscow foreign ministers' conference in April 1947. Although the victorious allies had pledged in 1945 to administer occupied Germany as a unit, mutual suspicions and conflicting agendas were sealing off their respective zones. In Moscow, both the Western allies and the Soviets seemed to approach agreement, then dug in their heels, preferring to assure the development they wanted at least in their own parts of the country rather than to gamble on losing influence over the whole.

The disputes were complicated: Americans feared the burden of reparation exactions that Russia felt had already been agreed to, and London and Washington were also concerned that the Soviets aspired to dominate the agencies that would administer a unified Germany. In addition, the Western allies, observing the increasingly repressive grip of the Communist-dominated Socialist Unity Party in the eastern zone of occupation, were unwilling to risk any such result in their regions. Meanwhile, the German economy was mired in shortages, flight from a vastly depreciated currency, stalled reconstruction, and a breakdown of urban-rural exchange. These stresses were leading to hunger protests and a continuing decline of the already vastly diminished production of mines and factories.

Nor was Germany the only region in distress. European trade had barely revived since the war. After a promising resumption of production in 1946, the delicate postwar economy appeared snarled in bottlenecks and demoralization. The 1946 harvest had been meager; the severe winter that followed had frozen the rivers on which barges normally transported much of the coal needed to generate electricity and run factories. Reconstruction required products from the United States; the Europeans did not have the dollars to purchase this material.

In the same months, East-West ideological divisions became ever more intractable. Russians and Americans had failed to reach agreement on the control of atomic energy; they had exchanged bitter messages on the control of postwar Iran; most dismaying, the East European countries that Soviet troops had occupied were forced into satellite status as Communist people's parties or spurious political fronts tightened their control over government, industry, and the press. In the West, Communist and non-Communist parties ended the coalition governments that they had formed in the immediate aftermath of liberation. The fading politicians, labor leaders, and intellectuals who still wanly hoped to bridge the deepening split were consigned to irrelevance and excluded from influence in the West; in the East, they were silenced, exiled, or imprisoned.

In March 1947, Washington agreed to assume Britain's role in supplying and in fact organizing the Greek government's fight against Communist guerrillas. As the president explained in what became known as the Truman Doctrine, the United States was prepared to extend aid to any government fighting subversive movements. The resounding declaration was designed for American political realities. The midterm elections of 1946 had returned a Republican Congress. Some GOP conservatives feared embroilment in Europe, but the majority of the party was prepared to support an anticommunist, bipartisan foreign policy. The "vital center"--to cite the expression of then Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. '38--would rally to define an anticommunist liberalism. Nonetheless, the Truman Doctrine was not an instrument for combating the discontents in Western Europe. Could not Americans offer something more positive and hopeful?

This was the challenge to which Marshall and his assistants responded in the six weeks between Moscow and Harvard Yard. The new policy planning staff under George Kennan coordinated ideas; everyone in the relevant agencies was soon eager to claim paternity, as Charles Kindleberger--then dealing with German and Austrian economic affairs in the State Department and for decades thereafter a vigorous economist and historian at MIT--pointed out in a humorous note on the origins of the plan. The concept that emerged was simple but innovative: Washington must make a multiyear commitment of foreign aid to those European governments that would respond cooperatively, in order to alleviate the dollar shortage, catalyze recovery, and preclude any reversion to authoritarian solutions.

The new assistance program, eventually christened the European Recovery Program (ERP), differed from the substantial aid provided ever since the end of the war. The United States had been extending roughly $5 billion in aid each year (from a peacetime GNP rising toward $200 billion) under the auspices of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency (UNRRA); the funds went to countries in eastern as well as western Europe, to Egypt, and to its own occupation forces. Washington had also extended or facilitated key loans to Britain and France. But Congress grew increasingly restive about these expensive stopgap infusions. Some UNRRA supplies flowed to Communist countries that became more and more hostile, or went toward relief measures that did not seem to promote any revival of production. The new program would target investment and reconstruction; it would include what today we call technology transfer, and involve advisers in economic modernization. Advocates stressed that ERP was not merely an anticommunist expedient, but an effort to encourage Europe to emulate the modern production methods that the United States had mobilized so successfully in fighting World War II.

From Marshall's speech onward, the Europeans were summoned to cooperate among themselves in assigning priorities--although the United States would sign a pact with each. The political astuteness of the project lay in its openhanded offer. No country was to be excluded: if the East European Communist regimes were willing to open their economies to scrutiny and cooperative trade practices--and undoubtedly to American investors and products--they could allegedly share in the resources. Did Marshall and his advisers really expect this result? Could they have persuaded Congress to authorize such assistance? Skepticism was warranted. But perhaps the Marshall Plan might persuade Moscow to move toward a more cooperative course, such as had seemed possible at the end of the war. If not, the onus for the break would be on the Soviets, and a critical mass of the West European working and middle classes, desirous of sharing in American aid, would rally around non-Communist leaders.

Not all these developments could be envisaged as part of a coherent strategy in early June 1947. But the key concepts were all implicit: sustained aid targeted for investment, growth, and balance-of-payments viability--not just for relief; aid profferred to a potentially integrated economic region, not just to individual countries; aid that would stress productivity and cooperation between capital and labor and would encourage Europeans to emulate the productive political economy of the United States.

Subsequent developments would shape the final outcome. Although Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov briefly attended the initial Paris conference of recipients in July, the Russians and the regimes they controlled soon withdrew. Moscow's leaders summoned foreign Communist parties together in September and warned them to prepare for a long period of hostile confrontation. The Communist parties of France and Italy soon engaged in a series of provocative and unsuccessful strikes to protest their recent exclusion from governing coalitions. In effect, Europe's Communists retreated into a political ghetto at Moscow's behest rather than risk losing their militant identity. They accepted the risk of isolating themselves rather than accept the risks of détente. The Czech government, still democratic and still a coalition, dared to remain in Paris for another few months until Soviet pressure compelled it to withdraw. The concession did not placate Moscow, and Communist factory committees and political leaders forced a dictatorial regime upon the country in February 1948. This final extension of Communist control helped to overcome remaining hesitation on the part of the American Congress to fund the recovery program.

Americans designed an innovative structure: an independent aid agency in Washington, the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), under former Studebaker Corporation president Paul Hoffman, who headed the effort, coordinated economic planning, and solicited the yearly appropriations from Congress. Former Lend-Lease administrator and Soviet ambassador Averell Harriman (followed in 1950 by future Harvard law professor Milton Katz '27, J.D. '31) headed the Paris ERP headquarters as special representative in Europe, and coordinated the country aid missions attached to each American embassy. Each country had to prepare recovery plans and have them approved by the new Organization for European Economic Cooperation (founded in 1948) and by the Americans. The amount allocated depended upon the projected balance of payments deficit; need, not virtuous austerity, opened Washington's purse. Once the European planners received approval for the matériel sought from the United States, the ECA bought the goods from American suppliers--steel and industrial raw materials, industrial components, wheat, foodstuffs, and tobacco--and delivered them across the Atlantic. The recipient governments then in effect sold the goods for local currency, termed "counterpart," to the national agencies or industries that had sought them. Marshall Plan officials retained a voice in approving the use of local counterpart funds. The French, for example, allocated their counterpart francs to Jean Monnet's national planning commission for specific infrastructure projects; the British won approval to reduce government debt, which in turn freed private capital for market-oriented investment.

In general, American advisers found it difficult simply to oppose the counterpart projects for which Europeans might plead; aside from vetoing the occasional rank pork-barrel proposal, it was hard to impose alternatives. Still, U.S. advisers could play constructive roles in collaborating on local development strategies; Hollis Chenery, Ph.D. '50, later to teach in the Harvard economics department, was instrumental in planning for Italy's Mezzogiorno region. The young economists who staffed ERP agencies had learned the new Keynesian doctrines just before the war. They appreciated large and integrated markets, but understood that sometimes government spending was required to help markets function. World War II had further demonstrated that governments could plan purposeful economic activity and mobilize productive resources.

How decisive an economic and political impact did the Marshall Plan exert over its four-year existence? By 1951, when, in the wake of the Korean War, the U.S. transformed the assistance program into the Mutual Security Administration, Americans had supplied about $14 billion in aid, probably between 1 and 2 percent of our gross national product for the period--roughly five times the proportional share we now allocate to foreign assistance. In the first two years of the program, American aid provided a major share of German and Italian gross capital formation; then it fell, as in Britain and France, to a much smaller share. In quantitative terms, Europeans were soon accumulating their own capital. Nonetheless, Washington's assistance satisfied key needs and was targeted to eliminate critical shortages. Assistance in dollars allowed Europeans to invest without trying to remedy their balance of payments drastically through deflation and austerity. This meant that economic recovery did not have to be financed out of general wage levels. Working-class voters (at least outside France and Italy, where strong Communist political cultures still thrived) could thus be rallied by politicians who offered gradualist social-democratic alternatives and remained friendly to the West.

Would Europe have "gone Communist" without the Marshall Plan? No, but the mean and dispirited politics of the late 1930s might well have returned. The Marshall Plan made it easier to inaugurate a quarter century of ebullient economic growth; it provided incentives for closer regional integration (especially the decisive European Payments Union of 1950, which Washington helped to finance); and worked to stabilize the consensual welfare-state politics that prevailed until the 1970s.

Such an outcome was hardly foreordained. Europeans and Americans had trapped themselves in destructive policies in the 1930s with catastrophic consequences. They could have done so again. But in the late 1940s, Americans and Europeans made constructive choices. Fifty years later, that moment in Harvard Yard gives us a lot to ponder. What policies will unleash innovative energies, transforming bleak prospects and dangerous impasses into opportunity? How do we recover that sense of public purpose, that confidence in our institutions?

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()