Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

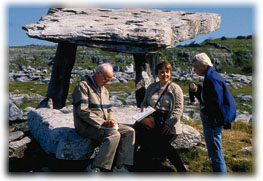

In the Burren region of County Clare, Elderhostelers compare notes beside a dolmen. Photograph by Jim Harrison

In the Burren region of County Clare, Elderhostelers compare notes beside a dolmen. Photograph by Jim Harrison |

Retirement may mean leaving a job. Accommodating advancing age may mean adapting to different living situations. But more and more frequently, people in their sixties, seventies, eighties, and older find that retirement is above all an opportunity for growth. Even as physical needs change with time, retirees discover that intellectual, emotional, and spiritual hungers stay as sharp as ever, and they are exploring new modes of exercising their intellects and interests, branching into new areas or exploring lifelong passions.

For many, perhaps particularly for alumni of Harvard and Radcliffe, retirement offers an opportunity to return to the academy and devote more time to learning. That impulse was the spur, 21 years ago, for the Harvard Institute for Learning in Retirement (ILR). Founded in February 1977, when a group of 92 men and women signed on as charter members, the ILR has registered more than 1,200 members who have gathered to study together in a program based on peer learning, with members serving as study-group leaders as well as students (see "An Academy for the Third Age," March-April 1997, page 28A).

What these lifelong learners study may have nothing to do with the working lives they left behind. In fact, for many, the freedom to explore is one of the most satisfying aspects of the institute. Milton Paisner '36, for example, enjoyed a sales and management career in the electronics industry. Fifteen years ago, when he was planning his retirement, friends told him about the institute. Since then he has led study groups on the joys and origins of the English language, and on authors and playwrights ranging from Oscar Wilde to Mark Twain. This spring he is conducting a group on Joseph Conrad. His wife, Martha (Kaplan) Paisner '38, has led groups on censorship and on the various roles of the American presidency.

Only about 25 percent of those who lead study groups are former academics, Milton Paisner reports. Such figures are close at hand and heart for him because he has been elected to the ILR's council five times and has served three times as its president. Reporting in the institute's twentieth anniversary bulletin last year, he wrote, "Why do I do it? It is fun--the thrill of research, the feeling of satisfaction when the course plan comes together, and then, the weekly meetings when you find out from the contributions of the class how much you missed in your reading of the material. It is also a challenge. It is what I look forward to each semester. It keeps me going."

This discipline may be what makes longer lives full. Professor of psychology Ellen Langer, a member of the Harvard medical faculty's division on aging, looked at how we create our own older age in her study Mindfulness. Her experiments have shown that by rejecting stereotypes of age and by applying themselves to new disciplines, people can invigorate both body and mind.

Maryel Locke '48 had already enjoyed two full careers before coming to the institute in 1994 with her husband, Laurence '39, LL.B. '42. The former lawyer says she turned to film studies because "I felt I needed some humanities." Her studies grew into another field of expertise, and led to her coediting a book of essays, Jean-Luc Goddard's Hail Mary: Women and the Sacred in Film (Southern Illinois University Press).

These days, she guides her institute colleagues through the joys and subtleties of cinema. It is hard work: preparing for her class involves reading and screening ancillary videos, selecting specific sequences in films that illustrate various points, and overseeing class reports. "I have learned a lot," she says. "Because I have to do so much work every week, I'm seeing more and more. I get to meet people. I enjoy getting them to see more, and I enjoy their reactions and their input."

For those no longer tied to the daily demands of a job or a growing family, retirement can be a time to activate some long-delayed travel plans. Since retiring 18 years ago, Charlotte Feldman, a former teacher, and her husband, Harold, a retired psychiatric social worker, have found time to travel for intellectual stimulation and sheer recreation.

The Newton, Massachusetts, residents are regular participants in Elderhostel, having tallied nearly 56 weeks with the educational travel and service group. The Feldmans admit that, despite a friend's urging, they felt some reluctance about joining the nonprofit group, which is open to those 55 and above, and offers programs at more than 2,000 sites around the world. "'It'll be all old people,' we said," Harold recounts, laughing. "That's what everyone says!" A one-week program at Amherst College convinced them that age does not have to mean boredom.

Since that 1979 experiment, they have joined Elderhostel for a variety of educational and touring vacations, including trips to Alaska (where they studied marine biology), France (where they took a barge trip), and Montana, Brazil, and Australia. Although they also ski regularly with a 70-plus ski club, Harold, now 83, credits Elderhostel with helping them explore the world. "Elderhostel is a wonderful way to go on trips you'd long thought about but never made," he says. "And we've made some good friends."

Groups such as Elderhostel can also broaden the horizons of single older people. Betty Hodges '31 says the group made a trip to the Grand Canyon possible for her, and it also offers writing classes that help her pursue this lifelong interest. (She has also led writing groups at the ILR.) A week-long retreat at Franklin Pierce College first hooked her on Elderhostel, she says; on a subsequent vacation she studied theater and wrote a play. Because Elderhostel often utilizes college campuses, she explains, it has the added benefits of being both more structured and less expensive than many other tour or education options. "When you're elderly and single, it isn't as easy to toot off on a vacation," Hodges says. "This gives you a little vacation that is also stimulating."

Planning for a fully active retirement may involve relocating to a community that will foster health, comfort, and an active lifestyle at any age. George Olive '39 and his wife, Priscilla ("Peeps"), moved to Carleton-Willard Village, northwest of Boston, three and a half years ago. "This way our children don't have to worry about us," the former physician says succinctly of their decision to join a continuing-care community. "And we don't have to worry about staffing at home. It's foresightedness."

The Olives still prefer to drive themselves around, rather than take advantage of such options as buses to Symphony Hall or the supermarket. But they are actively involved in their new community: Peeps has been elected vice president of the residents' organization, and George works at the gift shop once a week.

George Olive also volunteers, twice a week, as a reader for the blind. That commitment echoes those made by many other retirees. Eighty-two-year-old Erika Chadbourne, the former curator of manuscripts at the Harvard Law School library, now lives at the Cambridge Homes, another retirement community, but remains actively involved in the wider community as a volunteer. She has donated her time to Christ Church and the Schlesinger Library, but her main commitment is still to the law school library, where she organizes exhibits, sometimes working four days a week and up to two years on major shows about celebrated twentieth-century legal events like the Sacco and Vanzetti case, and legal figures like Justices Frankfurter, Holmes, and Brandeis.

She finds such volunteer work opens a path for lifelong learning, as well as extending her community. The people she meets are an added bonus. "I still see one of Justice Brandeis's great-granddaughters," she explains. And exhibits intrigue her with their details. "I like planning them out," she says, "and I like to be intellectually active. I'm very curious about what makes people tick."

Volunteer work like Olive's and Chadbourne's can carry a lifelong vocation into a stimulating retirement. Al Bernstein, Ed.M. '52, who has taught at the university level, says his days at the Service Corps of Retired Executives (SCORE) are as satisfying as any paying job. Bernstein, a Waltham resident, spent most of his career with General Electric, serving in the human-resources and public-relations offices. He joined SCORE in 1995, and began coaching small-business owners and hopefuls about the realities of their fields.

"We counsel them, help them put together a business plan, and tell them what factors they need to consider," says the 69-year-old about his volunteer sessions. "It's very rewarding. I get a great kick out of helping people who come in and tell me, 'I have a great idea'--and a year later I read in the paper that they've started a successful business."

Through such work, as well as by learning and teaching, traveling and sharing, retirees are enriching their communities and bringing new zest to the next stage of life.

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()