Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

And so it was that in June of 1958, Hanfmann gathered--for what he projected as a short campaign--a team of 15 archaeologists, epigraphers, architects, conservators, draftsmen, recorders, and assorted other enthusiasts, plus a local work crew. Right from the start, Hanfmann began compiling his extraordinary letters from Sardis. These charming dispatches were addressed, not (or not only) to potential big donors, but to interested laypeople. Their informative and chatty narrative style rivals that of Herodotus himself.

In the midst of arranging for housing, supplies, permits, and customs clearance--a tortuous maze of red tape--digging actually began, and, writes Hanfmann,

After that, the objects began to tumble up by the dozens. Using a horse-and-wagon, lift-and-drag technology hardly more advanced than that used at the Pyramids, the team found artifacts--vases, glass, inscriptions, sculpture, house walls, and coins--dating from the time of Croesus to the early

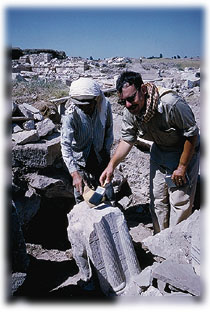

David Mitten (right) examines a monument to the goddess Cybele.©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

David Mitten (right) examines a monument to the goddess Cybele.©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

Directly, however, word got around. Sightseers and journalists began to arrive looking for the long-lost gold of Croesus. Armed state troopers appeared one night, saying they had been sent to guard the treasure. "Our first move," Hanfmann writes, "was always to explain that we had not found the treasure of Croesus, and, indeed, believed that Cyrus had taken it long ago." He found himself refuting the rumor of recovered riches again and again during the 19 years of his directorship.

A circuit of the site would be "a matter of at least three miles" of topographic complexity, he estimated, including the acropolis, about a thousand feet high. Members of the staff used to make the rounds of the circuit regularly, up to four times a day, in the sweltering heat. Those indeed were the "heroic days," as he not altogether jokingly claimed. He later remarked that "car-driving and smoking (as in Cambridge) does not put one in good shape" for such demands. But what seems abundantly clear is that, withal, they had a marvelous time. Despite tremendous discomfort, withering heat, poisonous snakes, scorpion bites, and "King Croesus' revenge," their delight in just being there is evident.

Revetment plaque from the synagogue, preserving the Hebrew word shalom. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Revetment plaque from the synagogue, preserving the Hebrew word shalom. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

The 1959 season starts out lyrically as well, with "two storks solemnly approaching us in the manner of a reception committee looking for all the world as if they were dressed in coat-and-tails"; with "violent blotches of red" rhododendrons; and with "soft white clouds" lying "against the twin peaks where Dionysus was born in the golden ages of gods."

That season, too, saw the introduction of two young Harvard men to the dig. The first was Crawford H. Greenewalt Jr. '59, who came as a photographer. Greenewalt, now professor of classical archaeology at Berkeley, was destined to succeed Hanfmann as field director in 1977. It must also be noted that Greenewalt, known to everyone as Greenie, was destined to carry on the lively narrative tradition of his mentor's letters from Sardis.

The synagogue as restored by the expedition to its fourth century c.e. phase, with a pedimented pair of shrines at its eastern end. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

The synagogue as restored by the expedition to its fourth century c.e. phase, with a pedimented pair of shrines at its eastern end. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

The other to arrive in 1959 was David Gordon Mitten, Ph.D. '62, now Loeb professor of classical art and archaeology, Hanfmann curator of ancient art in the Harvard University Art Museums, and an associate director of the Sardis excavation. "Dave Mitten," wrote Hanfmann admiringly, "is the enthusiast of the expedition; while others relax after the hot day in the trenches, he is ranging uphill and down, loading himself with sherds until he comes back panting under his archaeological load." Mitten became associated that year with the provocative Building B, a massive structure near the highway that was soon revealed to be a huge Roman bath-gymnasium complex with a string of late Roman-Byzantine shops attached to its south side. It would be another three years before a section of Building B would emerge as arguably the most significant discovery and restoration project of the entire Sardis expedition: the largest known synagogue of the ancient world.

Leading to this discovery was the study of a giant trench filled with "traces (tons of them) of a mighty and richly decorated colonnade."

This sector, comprising the rectangular area to the east of B, had been going like wildfire in the last days of the dig. It was Tom Canfield's [professor of architecture at Cornell] architectural eye that had divined under the unshapely hillocks of earth a large structure leading to the center of B. As supervisor of the area he laid out the plan of attack, and the actual excavation carried out by Dave Mitten vindicated Tom's surmise....

"Tom's surmise" was that a magnificent court area, colossal and richly decorated, waited to be excavated. This area, named the Marble Court, which eventually became another major restoration undertaking, "turned out to be one of the most impressive examples of Roman Imperial architecture in Asia Minor," according to Hanfmann. In clearing the Marble Court--a feat involving some acrobatic legal maneuvers in purchasing the surrounding land from 11 heirs--features of the adjoining (though not yet identified) synagogue kept showing up as well.

Then, in August of 1962, Hanfmann sends the news:

Burial mounds in the Lydian royal cemetery at Bin Tepe, with the acropolis of Sardis and the Tmolus Mountains in the distance. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Burial mounds in the Lydian royal cemetery at Bin Tepe, with the acropolis of Sardis and the Tmolus Mountains in the distance. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

The Hebrew inscription read shalom. According to epigraphist Frank Moore Cross, Hancock professor of Hebrew and other languages emeritus, who analyzed the Sardis Hebrew inscriptions--seven were ultimately found--the word shalom or "peace" is "ubiquitous in inscriptions from synagogues and on epitaphs. Often it is the lone Hebrew word in a Greek or Latin inscription." The other Hebrew inscriptions, according to Cross, include the names of Jewish donors, and they date to the second half of the third century or to the fourth century c.e.

But it is the inscriptions in Greek, some 80 of them, which, according to John H. Kroll, Ph.D. '68, professor of classical archaeology at the University of Texas, "show a completely assimilated community, to the extent that there is very little except in terms of the religious affiliation which is identifiably Jewish. Had there not been a few menorahs found, either as graffiti or made of actual stone, the building would have been assumed to be a Christian church." In fact, it is not impossible that the Sardis synagogue--with its porch and atrium with fountain, its unusual Roman-eagle altar, three raised benches for the elders, and basilical plan--served as a prototype for later Christian basilicas.

Crawford Greenewalt (right) debates Lydian pottery with conservator Anthony Sigel. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

Crawford Greenewalt (right) debates Lydian pottery with conservator Anthony Sigel. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

Further, according to Andrew R. Seager, professor of architecture at Ball State University, who has written about the synagogue architecture, the Greek inscriptions point to a Jewish population of great vigor and substance, one that had flourished in Sardis since the sixth century b.c.e., its numbers augmented during the third century b.c.e. by Jewish families transferred from Babylonia, and its rights under the Romans in the first century b.c.e. mentioned by Josephus. The inscriptions, as Seager tells us, indicate a prosperous, esteemed Sardian Jewish community: "Most of the inscriptions pertain to the gift of interior decorations and furnishings made in fulfillment of vows. One of them refers to the marble inlay decoration of the nomophylakion, 'the place that protects the Law,' which must be the Torah shrine. The donors' names are often followed by the title 'citizen of Sardis.' Eight men are also identified as members of the city council (bouleutes), a hereditary position open only to the wealthier families in Greek cities under the Late Empire....Other office holders mentioned are an assistant in the state archives, a former procurator, and a count."

And John Kroll calls attention to perhaps the most fascinating of the inscriptions, a complete marble plaque, its text reading "Having found, having broken, read, observe." Since, according to Kroll, "the concluding imperatives surely relate to the reading and observation of the Law, the inscription was almost certainly displayed in connection with the Torah shrine." (The shrine itself, one of a graceful pedimented pair, has been restored at the eastern end of the synagogue.)

How and why the original southern section of the gymnasium--originally intended perhaps as dressing rooms or a gathering place--evolved into a synagogue remains a mystery. Marianne Palmer Bonz, Ph.D. '96, managing editor of the Harvard Theological Review, proposes that it had served as a meeting hall for the elders of Sardis. She suggests that "the Jewish community acquired the South Hall and began converting it into a synagogue at or just before the turn of the fourth century and that the process took about 75 years to reach completion."

According to A.Thomas Kraabel, Th.D. '68, professor of classics and religion at Luther College, the Harvard-Cornell work on the synagogue has stimulated research on diaspora Judaism, particularly that of Asia Minor, in the first centuries of our era. "Before our work on the synagogue, people who wanted to know anything about Judaism in Asia Minor would take the evidence of the New Testament," he says. "Well, that's a very limited angle of perspective. The New Testament is interested in telling the Christian story, and diaspora Jews become characters in that story. This is a story that portrays Jews as a kind of enemy, alien to Asia Minor, unhappily exiled from the land of Israel. It may have looked that way to the early Christians, but I don't think the Jews of Asia Minor spent a lot of time worrying about the Christian perception. After all, they were hardly alien; they had been in Sardis for hundreds of years."

Like others of his colleagues, Kraabel emphasizes the archaeological evidence that Jews and Christians lived and worked amicably together in the Byzantine shops. David Mitten, however, cautions against reading into the ancient scenario "too much happy harmony, long before B'nai Brith, with everybody dancing the hora in the marketplace." Kraabel himself has written an account of the vituperative anti-Semitism of Melito, a second-century c.e. bishop of Sardis. Nevertheless, Kraabel emphasizes that "the excavation of Sardis has opened all kinds of new investigations into Judaism and Christianity in this period."

The hard evidence documenting early Christianity in Sardis, though fragmentary, indicates a burgeoning and vital community. Beginning with David Mitten's find in 1959 of a marble basin incised with crosses in one of the Byzantine shops, a number of Christian-related objects--pilgrim flasks, utensils, a finger ring, and the like--have turned up, as well as hundreds of Christian graves, including some beautifully decorated tombs. Just last summer a fragment reading "Holy is God" was found over a residence doorway in a Late Roman neighborhood where large crosses have already been found as home decorations.

Remains of several early churches have also been found, including a fifth-century chapel built onto the Artemis temple and the fourth-century "Church EA," which appears to be one of the earliest churches outside Rome and the Holy Land. What is interesting, as Kraabel notes, is the relatively modest size and location of EA, compared with the contemporaneous synagogue, seating more than a thousand and, by all accounts, splendid.