Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

A section of the Lydian fortification wall's façade (right), with its tumbled, still undug, upper part at left. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

A section of the Lydian fortification wall's façade (right), with its tumbled, still undug, upper part at left. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

The synagogue, ironically, has yielded abundant archaeological evidence about the religion that had prevailed in Sardis long before the dawn of Christianity--the cult of Cybele. In the summer of 1963, Hanfmann exclaimed,

A unique monument of archaic art celebrating the great goddess of Lydia, Cybele, has just been discovered. To the surprise of the excavators this jewel of archaic sculpture was found among the ruins of the Synagogue of Sardis.

She was found by David Mitten, or Daoud Bey, as the Turkish workmen were now affectionately calling him, in the year he recalls as that "incredible season of '63, when the stuff was just pouring out."

To Hanfmann, the synagogue was "a veritable mine of archaic sculpture," recycled for later use, including two pairs of addorsed lions, sacred to Cybele but "reincarnated as symbols of the Lion of Judah." In the summer of 1968, a double relief was found face down in the synagogue. It featured the two goddesses, Cybele with her signature lion, and her successor, Artemis, with her attribute, the hind. The two figures placed together confirmed for many scholars that Artemis was not a later version of Cybele, as had been suggested, but that the two were separate deities. In 1963, Hanfmann had postulated that remains of the archaic sanctuary of Cybele "must have been 'stockpiled,' perhaps after the disastrous earthquake of a.d. 17; the sanctuary must have been somewhere near the site of the Synagogue."

In fact, Cybele was honored at more than one shrine. An important site was on the east bank of the Pactolus, whose gold-bearing sands, as noted, were the subject of so many stories in antiquity. Here, where the gold was processed, was where Cybele, goddess of the mountains, guardian of ores and metals, was worshipped. As Mary Jane Rein, Ph.D. '93, writes in her doctoral dissertation on Cybele,

She was worshipped in wild gratitude for the gold, suggests Rein, "with mountain processions and rituals," orgiastic dances and maenadic rites like those devoted to Dionysos.

And here indeed, under Cybele's protection, were found traces of Croesus' gold refinery. In the summer of 1968, the exuberant Hanfmann sounds like a devotee himself:

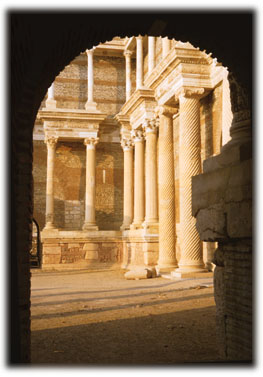

The Marble Court, part of the bath-gymnasium complex, as completed in 211 c.e. and restored by the expedition. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University

The Marble Court, part of the bath-gymnasium complex, as completed in 211 c.e. and restored by the expedition. ©Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/Harvard University |

It all began on July 6, when archaeological detective [Andrew] Ramage [Ph.D. '70], tenderly brushing a clay floor, perceived the outlines of little greenish rings. They proved to be depressions lined with clay and ashes. Some heavy, grey matter adhered to the inside of one of them. Ramage's hunch that the little hollows had something to do with metalmaking set off the hunt. The Importance of Having the Right People at the Right Place in the Right Time was gloriously upheld, as scientific detective Dick Stone developed the technical interpretation of clues and detective Sid Goldstein [Ph.D. '71] ran the tests to prove them.

The grey matter proved to be lead slag with traces of silver. The depressions, Dick felt sure, were cupels, fire-resistant containers for purification of gold or silver. Cupellation involves extracting impurities out of silver or gold by heating them with lead.

For a week or so, we had the theory, the cupels, the lead, and the traces of silver, but no gold. Then keen-eyed assistant Halis Aydintas¸bas¸ spotted a tiny speck of gold. As the technique of sifting and searching the clay floors and industrial refuse became more proficient, more and bigger specks of gold appeared. More important than these scattered gold bits are the traces of gold left in cracks of crucibles (clay vessels). They prove beyond doubt that gold was being treated and melted here.

"Archaeological detective" Andrew Ramage, now professor of the history of art at Cornell and associate director of the Sardis expedition, is author, with Paul Craddock of the British Museum, of a forthcoming book about this find, King Croesus' Gold Refinery at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining. Ramage says that the cementation process--that of separating gold and silver from the natural mixture known as electrum (with salt being the major parting agent)--used at Sardis has not been found elsewhere. "The unique evidence at Sardis," he says, "makes other evidence from all over the classical world much easier to understand. It helps us to deal with some of the recipes which had not been making much sense until now." "Hooking up," he continues, "with the British Museum has expedited the work; they provided resources, and they had up-to-the-minute gadgets for analyzing the gold pieces and other things we found--slag, bellows nozzles, bits of old lead--all sorts of things that don't look like much but are extremely important to the technology."

If Croesus' secrets of minting gold and silver separately seem over time to be yielding to investigation, not every Lydian enigma is so tractable. Herodotus, as it happens, was not nearly so impressed with the gold-refining process as he was with Bin Tepe ["1,000 mounds"], the great burial mounds of Lydian royalty, a magisterial sight of more than a hundred surreal swellings that even today captivates the most casual tourist. Particularly impressive to Herodotus was the tomb of Croesus' father, Alyattes, which he called "the greatest work of human hands in the world, apart from the Egyptian and Babylonian":

The only way to the chamber tombs, or whatever lay in the bosom of such a tumulus--a thousand feet, three football fields, in diameter--was tunneling. And tunneling experience they had. Greenewalt had found and burrowed into ancient tunnels in the acropolis of Sardis, topped with its picturesque Byzantine ruins, as early as 1960. Greenie, the Hanfmanns, and others had crawled fearlessly through the heat and collapsing passages and had excavated as far as 144 meters of down-spiralling tunnel into the acropolis before throwing in the trowel in 1964 and concentrating life, limb, and finances on further exploring the royal tombs of Bin Tepe.

In 1853 consul Spiegelthal had driven a tunnel into the south side of Alyattes' mound and had found an antechamber and a chamber, but Harvard-Cornell's attempts were foiled by clogged tunnels, collapsing rubble, limited air supply, mosquitoes, and furnace-like heat. This in spite of the fact that, to add insult to injury, illicit diggers for centuries had not seemed noticeably impeded--even, at times, leaving their trash behind, as if in mockery of earnest labor.

In 1962, Hanfmann had detailed the last efforts of the season to subdue Alyattes' mound. The group included "Mrs. Hanfmann--whose lion-like (aslan gibi) courage is renowned among the workmen since she made it all through the Acropolis tunnels." They "crawled, sweated, panted, and squeezed in the threatening underground world, hauling their instruments with them." The team photographer "shot off flashbulbs and slid among rubble to take the first picture ever taken of the burial place of Lydia's mightiest king."

Two years later, Hanfmann "drew a bead" on another huge mound, this one called "Split-Belly Mound," from gashes made by ancient tomb robbers. He established this as a priority: a "three-shift job 24 hours around the clock, six days a week," with railway, generator, and transformer for lighting the tunnel. He even hired professional miners.

Hanfmann was fairly sure they were dealing with the burial mound of King Gyges, ancestor of Croesus. One of the thrills of the work was finding, buried deep inside the mound, a six-and-a-half-foot-tall "beautifully worked retaining wall, two courses high, crowned by a third course in the form of a big rounded molding." On this wall were 10 signs (more were found subsequently) which Hanfmann felt referred to Gyges: "I have found a way of reading the sign which appears on the wall as a monogram of GY-GY, Gugu, the name of Gyges in Assyrian annals...."

Occasionally in the letters of Hanfmann, and later Greenewalt, there appears a head-scratching ambivalence about continuing work on the mound. For one thing, during Greenewalt's tenure, it became clear that the tumulus was about a century too late to be the tomb of Gyges. The tomb in Not-Gyges mound (as it is now called) thus assumed the status of a needle in a 160-foot- high, 700-foot-wide haystack, a chamber that might, besides, have been rifled by tomb robbers long ago. On the other hand, with or without Gyges, "It is too tempting to write it off completely," says Greenewalt. Remote sensing, by radar, magnetometry, and resistivity testing--all used at Sardis in recent years-- would seem to offer efficient alternatives, except that these methods present problems, too, particularly of non-specificity. As Greenewalt says, "We still need to validate the high-tech findings with low-tech excavation."

"In the battle of Man against Mound, the Mound won," sighed Hanfmann tentatively in 1964. Or did it? Hanfmann died in 1986, but, concerning the unknown Lydian royal, Greenewalt is still ruminating.

If the Kings of Sardis in death have by and large kept their secrets, the lives of everyday Sardians are gradually revealing themselves. The excavators had long known of a Lydian fortification wall, but it was not until 1976 that "archaeological detective" Andrew Ramage and his wife, Nancy H. Ramage, Ph.D. '69, now professor of art history at Ithaca College, discovered it. Ramage recalls,

I first noticed a hillock right opposite the synagogue on the side of the road. It was an artificial construction rather than an act of nature; in fact, what we were looking at was solid mud brick, unbaked individual pieces of adobe. In 1977 we determined not only that it was indeed artificial, but that it had an edge and was at least 60 feet thick. And we had left about 20-odd meters of the face; when we were able to dig away the material that had slumped down on it, we were left with this mud brick rising smoothly from a stone basis for 20-odd feet.

During the 1997 season, a resistivity survey showed a "black slug" on the computer--more of the wall and where it might have gone. "finding where the wall goes," says Ramage, "will help us decide which is the inside and which is the outside of the wall, Lydian remains having been found on both sides of it. At the moment it doesn't make a definitive enough turn to let us be certain. There are continual discussions and several cases of beer riding on the outcome."

This monumental mud-brick structure represents the defending walls of Sardis, violently breached and burned, according to all subsequent finds, sometime in the mid sixth century b.c.e., just when Sardis was putatively conquered by Cyrus. Weapons associated with that battle have been excavated over the last few years: a cache of arrowheads, a saber, a helmet, and the pieces of a chariot. Also found were the skeletons of two casualties, one of whom, a young soldier, was just about to throw a stone.

Excavated, too, was a residential quarter located near the fortification, and destroyed by fire along with it. Perhaps most important in terms of dating the catastrophe is the great quantity of pottery found there. Greenewalt's description is touching:

Most of the pots--200 odd--were for serving and preparing food--stews of mutton, pork and beef, along with bread and porridge....Others were for salves and lotions....Spinning and weaving activity is indicated by many spindle whorls and loom-weights; the latter come in five different modules--for fabric of different lengths or yarns?...One jumble also included remains of a right-angle wooden thing with iron braces, possibly the upright and crossbar of a loom, but too burnt to reconstruct.

At last, Hanfmann's dream--the everyday Sardis of Croesus. Not so fast. "The Tyche [guardian spirit of Sardis]," says Greenewalt, "never gives up her secrets without a tease." In fact the Romans, from the fourth to the seventh centuries c.e., decided to build a wonderful neighborhood right into the Lydian defenseworks. As Marcus Rautman, associate professor of art history and archaeology at the University of Missouri, says, "Collapsed mud brick makes a terrific foundation material. The Romans were builders par excellence, and they knew the sturdiness and high-compression strength of this debris."

This apparently tony suburb, as described by Greenewalt, contains a "real somebody's" home, featuring "a Great Hall of cockeyed design with apse and niches; fallen window column and window glass, a reception room with mosaic floor; eventually downgraded to feature a latrine--the seat grandly placed near the middle of one wall, opposite the nine-foot-wide room entrance!--and later, a baking oven, and a porter's hall. Beyond the three rooms is an alley--only partly excavated but indisputably identified by its large subsurface drain, which defines house limits on the one side where limits were previously unknown, thus helping to establish for the house a total ground-floor habitable-space area of 3,500 square feet and room count of 12...."

Clearly, no excavator--"even the most unprincipled butcher," says Greenewalt--would propose, for the sake of exposing Lydian houses, wholesale removal of the Roman suburb, which is "like Scheherazade, full of riddles and stories too intriguing to justify summary execution." How then, asks Greenewalt, "can we protect and make intelligible to visitors these monuments of Lydian and Late Roman eras, separated by a millennium in time and a few feet in vertical space?" Inevitably, there must be a species of triage, "some Late Roman-Lydian horse trading...Lydian buildings will have to remain unexcavated or be backfilled in order to display deserving Late Roman ones above, and Late Roman buildings already have been sacrificed to expose Lydian beneath." In the plans, too, is "selective reconstruction of both eras."

Though Hanfmann had visualized a campaign of limited duration, the fact is that, at the 40-year mark, less than 10 percent of the site has been excavated. The tantalizing work ahead will perhaps uncover further information about an even earlier era: prehistoric life at Sardis, for which--thanks to David Mitten and others--there appeared "a cloud of witnesses," as Hanfmann put it 20 years ago, including "mighty pithoi, spindle whorls, and tools" found along a nearby lake. There are also plentiful examples of Bronze Age pottery, a few of which seductively suggest the presence at Sardis of Mycenaeans--perhaps the "Sons of Heracles" mentioned by Herodotus? To Greenewalt, a major puzzle begging clarification is the lack of archaeological evidence from the Hellenistic era of Alexander the Great, known to have conquered Sardis in 334 b.c.e., and his successors. After all, says Greenewalt, Alexander's only full sister--another Cleopatra--lived at Sardis for a while. "So where," he asks, "are the big Hellenistic public monuments which Sardis must have had? We have to assume they'll be found in the unexcavated area."

Much to do. Enough, says Greenewalt, for another 40 years--at least.