Main Menu · Search ·Current Issue ·Contact ·Archives ·Centennial ·Letters to the Editor ·FAQs

New TricksSam Keen proves age, like fear, can be just a state of mind. Man on the flying trapeze Sam Keen, author of Learning to Fly. Christine Shipp

Man on the flying trapeze Sam Keen, author of Learning to Fly. Christine Shipp |

Once called a "hairy-chested Jungian" by Time magazine, Keen has never been the stereotypically pasty scholar. But he was a professor of the philosophy of religion for a time after graduating from the Divinity School (where he was "happy as a hog on holiday," studying with theologian Paul Tillich, among others) and earning a Ph.D. at Princeton. A sabbatical after six years at the Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary convinced Keen to leave academe to write for the lay audience, and, after a move to California in 1968, he began his 20-year association with Psychology Today as a contributing editor. He's been a very successful freelancer. In fact, if his latest interest seems to be an indulgence, it is supported by what he calls the "felicitous timing" of his fourth book, Fire in the Belly.

Photo by Peter DaSilva

Photo by Peter DaSilva |

Published in 1991, just at the crest of the men's movement perhaps most strongly associated with poet Robert Bly '50 and his book Iron John, Fire in the Belly suggested ways for modern men to redirect their "masculine" drives. The book spent several weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, and royalties helped Keen buy his 60-acre ranch in California wine country--enough room for an outdoor trapeze rig.

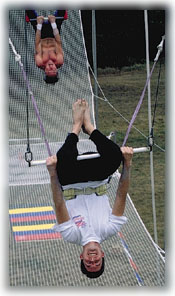

Learning the trapeze is the fulfillment of a childhood dream for Keen, and, he says, it's been a heady experience to explore it at such an advanced age. "I'm always trying to learn harder tricks," he adds. "Every time I think I've come to a limit, I'm wrong. It's a source of enormous joy." He spends a significant amount of time helping others overcome those limits as well, but not without difficulty. Though Keen says he loves "the discovery of fear," many of his students aren't similarly inclined. He witnesses severe panic attacks regularly. "We had to let one abused woman down by the safety ropes," he recalls. "She sat shaking for a half hour before we could get her up again."

Unready for their close-up: the author and Sam Keen (background) just before an unsuccessful attempt at a "catch." Molly Harrell/Courtesy of Omega Institute

Unready for their close-up: the author and Sam Keen (background) just before an unsuccessful attempt at a "catch." Molly Harrell/Courtesy of Omega Institute |

But Keen is convinced of the value of the exercise, both physical and mental, and contends that "living in the presence of fears is a lot better than letting them go underground, unconscious." He tells of rival gang members who spontaneously begin to mingle, advising one another, after a lesson. The exhilaration is undeniable. "This is a lot better than drugs," Keen recalls one teen saying. "Because you can feel it."

it's natural to invest authority in anyone who may push you from a height, but Keen elicits a special confidence among his students, who rave about the power of his example. At the Omega Institute, a fellow attendee told me that Sam had such a strong presence up in the rig, it "seemed like he had the voice of God." (She amended the statement later, saying, "I decided it's the voice of Gregory Peck." Said Keen, in his mild drawl, "That sounds like a promotion.") Confidence in Keen is necessary, since one of the first triumphs for his pupils is to be caught by him from a knee-hang position.

I can attest that my lesson helped me conquer fears, not least of which was the fear of wearing tights in public. Trapeze is not an activity many of us have seen done poorly. Consequently, almost everyone looks foolish doing it. I found it therapeutic to have to concentrate so intensely on not killing myself that there was little chance to be the least bit self-conscious otherwise.

It's affirming, also, to see the pluck and enthusiasm such an odd pastime as amateur trapeze can inspire. After lunch, Keen's class watched videos of legendary flyer Miguel Vazquez, the first man ever to perform a quadruple somersault. Keen was rapt as a child until a student asked, "What age do trapezists retire, Sam?" "About 40," he said slowly. "Catchers a little later...about 75."

~ Daniel Delgado