![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()

Main Menu ·

Search ·

Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

Father J. Bryan Hehir is the new leader of Harvard Divinity School, the first Roman Catholic to head the school on more than an interim basis. He and president Neil L. Rudenstine, who announced the appointment on August 11, agreed that Father Hehir (pronounced hare) would not be called dean, but rather chair of the Divinity School executive committee, and would share some of the duties of a dean with other senior administrators and faculty.

Hehir had held that position on a temporary basis since last fall, when former dean Ronald Thiemann resigned suddenly; it was later revealed that he had had pornography stored on his Harvard-owned computer ("A Dean's Departure," July-August, page 78). An ordained Lutheran minister, Thiemann is now on sabbatical from his position as O'Brian professor of divinity, but is due to return to teaching and research in 2000. A nationwide search for a successor followed his resignation.

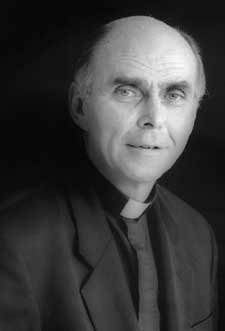

Father J. Bryan Hehir. Said President Neil L. Rudenstine when announcing the appointment, "His combination of qualities--humanity, leadership, intelligence, judgment, commitment, and administration ability--is quite simply superb.". Photograph by Tom Farrington |

By eschewing the title of dean, Hehir means "to signal people that I do have preexisting commitments outside the school that need to be fulfilled and that will have some impact on my ability to do the job here in terms of time and space."

His "intense interest in international relations and foreign policy, and in the church in foreign policy," for example, has made him counselor to Catholic Relief Services, the relief and development agency of the Catholic bishops of the United States. He provides policy analysis and advice to the Baltimore-based agency, which works in 85 countries, including Kosovo, Bosnia, and East Timor.

As professor of the practice in religion and society at the Divinity School, Hehir's habit has been to spend the first three days of each week teaching two courses at Harvard and the next two days at Catholic Relief Services. Now he spends just one in Baltimore. This semester he is teaching a course on the Catholic social tradition and another on Catholic bioethics and its relationship to social ethics, in which he explores some of the most controversial positions the Catholic Church takes. He is also a faculty associate and a member of the executive committee of the Center for International Affairs at Harvard.

Ordained in 1966, he is a priest of the Archdiocese of Boston and can take no position anywhere without consulting his superiors, who include Cardinal Bernard Law '53. He has pastoral responsibilities, mostly on nights and weekends, at St. Paul's in Cambridge and at the Church of the Resurrection in Ellicott City, Maryland. "My outside commitments," Hehir says, "are part and parcel of what I'm about."

Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1940, he grew up in Chelmsford and even as a boy was well focused: as a Little League pitcher, his nickname was Hawkeye. He earned an A.B. and a master of divinity degree from St. John's Seminary in Boston and a doctorate of theology from Harvard in 1977. From 1973 to 1992, he was in Washington, D.C., dividing his time between the U.S. Catholic Conference of Bishops and Georgetown University, where he was Kennedy professor of Christian ethics and research professor of ethics and international politics. He is credited with being the chief author of the pastoral letter on nuclear policy issued in 1983 by the U.S. Catholic Conference. The next year Hehir was awarded a MacArthur fellowship. He has received many other awards and 25 honorary degrees.

"He's a brilliant, brilliant student of politics--especially the geopolitical scene," says Archbishop Thomas Kelly, former general secretary of the U.S. Catholic Conference, who was quoted in the Boston Globe. "At the same time, he has never lost touch with his roots as a pastor. His life is ordered around the service of people, and he doesn't distinguish between the powerful and the helpless. He's the real thing."

At the top of Hehir's agenda is the launching of a conversation among the school's faculty that will lead to "a consensual position on a series of major substantive issues." Does the school need to revise its curriculum, for instance? And how does the answer to that question intersect with the need to make a series of faculty appointments, necessitated by a host of retirements?

The school prepares some students for ministry and leads others to doctorates and careers in teaching. Doing both things is one of the school's distinctive and great strengths, says Hehir, but strains time and resources, and the commitment to do it needs continual renewal.

Moreover, the faculty needs to be constantly sensitive to a changing student body. "In recent years, we have had extraordinary growth of interest in the master of theological studies degree," says Hehir, "which for the most part is pursued by people who intend neither to teach religion nor enter the ministry, but want an intellectually grounded understanding of religion before going into business, law, medicine, or politics. They have a conviction that what they want to do in life is to draw from religious resources and to contribute to a certain religious vision operating in the world.

"Another set of questions that needs attention from the faculty," says Hehir, "follows from the diversity of traditions now cultivated here. More so than most theological schools in the country, we place strong emphasis on studying the great world religions. This year, for instance, we will begin a search to fill a new chair in Buddhism."

Thomas H. O'Connor, university historian at Boston College, wrote in an op-ed piece in the Globe: "It is almost inconceivable that a Roman Catholic priest should take over the leadership of a divinity school whose original purpose was to deny Roman Catholics entry into a colony which at one time denounced their religious ideas as blasphemous and heretical, and which subjected its priests to death and persecution." Says Hehir, "I think it probably would not be possible to conceive of this appointment if we hadn't had the past 30 years of ecumenism."

Main Menu ·

Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

![]()