Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

The greatest success story in United States environmental policy to date has probably been the rapid and complete disappearance of leaded gasoline. "In the 1980s, we eliminated leaded gasoline from the market over a five-year period," says Robert Stavins, Ph.D. '88, Pratt professor of business and government. "Lead was phased out faster than anyone thought possible." Indeed, the lead content of gas fell by 90 percent, with a parallel drop in lead oxide--which can cause learning disabilities in humans--from car exhaust.

The government achieved this result by creating a system of permits that petroleum refineries had to purchase in order to add lead to gasoline. Since refineries could trade these permits among themselves, a plant that did exceptionally well at eliminating lead could sell its unneeded allotment of lead permissions to another refinery that was falling short of targets. There was a direct financial incentive to produce unleaded fuel, since the permits were convertible to cash.

Graph by Stephen Anderson |

Since the 1980s, sophisticated economic analyses have found more ways to turn market forces in green directions. In July, a Kennedy School conference on "Market-Based Instruments for Environmental Protection" drew 175 economists from five continents to discuss the state of the art. "Giving incentives to firms or individuals to do the right thing leads to any given level of environmental protection being achieved at lower overall costs," says Stavins. "These measures are cost effective." And they are in ascendance: in the important area of global climate change, for example, "virtually all the attention is on market-based approaches," says Stavins, who chairs the group that advises the Environmental Protection Agency on economic dimensions of environmental policy.

Much of the first wave of environmental legislation was " command and control" regulation--for example, laws that mandated specific technologies, like catalytic converters for automobile exhaust. "This kind of regulation tends to lock in existing technology," says Stavins. "The car companies might be able to come up with something better than catalytic converters, but the law provides little incentive for research and development. It's perverse."

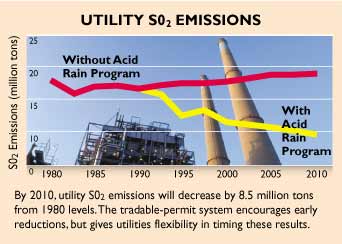

Consider acid rain, a consequence of air pollution that begins with sulfur-dioxide emissions from electrical power plants. The "command and control" approach might require all power utilities to put "scrubbers" on their smokestacks to reduce SO2 emissions. "That's very costly overall, particularly for older plants that might only have one or two years of life left," says Stavins. Instead, amendments to the 1990 Clean Air Act established a tradable-permit system for emission control. The goal was to cut SO2 emissions nationally by 50 percent by 2005. Some power plants with easy access to low-sulfur coal might be able to cut back considerably more than 50 percent; they could then sell their sulfur-dioxide permits to a power company with greater need for them. The regulatory goal, after all, is to improve the air quality nationally, not to ensure that each individual plant meets a defined standard. "It's been a highly successful program," says Stavins. "Since it went into effect, it has already cut sulfur-dioxide emissions by 50 percent, and is saving consumers about $1 billion per year." Some activist environmental groups, in fact, have bought SO2 permits and simply burned them, thus tightening the cap on acid rain in the United States.

A similar model might apply to global warming, a consequence of carbon-dioxide buildup from the burning of fossil fuels, principally coal. There is talk now of establishing an international system of taxes and tradable permits for the carbon content of fossil fuels. "Reductions in CO2 emissions can take place more cheaply in a country like China, because their energy generation, using old-fashioned coal plants, is inefficient," says Stavins. "On the demand side, their energy use is also wasteful. By purchasing permits from China, more developed countries in the West could essentially subsidize China's conversion to greener energy technology."

Market-driven instruments also have relevance to water pollution and ecological battlegrounds like development; Stavins speaks of transferable development rights as an alternative to zoning to help preserve threatened habitats like wetlands. "It's an information problem," he explains. "Government doesn't have the information you need to know where and when to make available all the products people want to buy--including clean air and water. That's precisely what a market does."

~ Craig Lambert