Main Menu · Search · Current Issue · Contact · Archives · Centennial · Letters to the Editor · FAQs

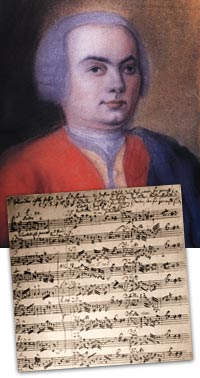

A 1733 pastel portrait of C.P.E. Bach. Below, a page from one of the C.P.E. Bach scores recovered in Kiev, Ukraine. |

LAST JUNE, more than half a century after its disappearance, the musical estate of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788), second son of Johann Sebastian Bach, was found in Kiev, Ukraine. The discovery amounts to a scholarly detective story whose head sleuth is Mason professor of music Christoph Wolff, historian of music and dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. The Bach breakthrough climaxes more than 20 years of work during which, Wolff says, "I tried all kinds of avenues without any success."

The C.P.E. Bach archive includes music by his father and brothers, a collection of works by his father's ancestors called "Old-Bach Archive" (many copies are in J.S. Bach's hand), and the greater part of C.P.E. Bach's own compositions in autograph or authorized copies, including 20 Passions and more than 50 keyboard concertos. Most are unpublished and have never been available for performance or study; many Western scholars had feared that they had been destroyed. For more than a century, the works resided in the eighteenth-century music collection at the Sing-Akademie in Berlin. Though known as a major music collection, the Sing-Akademie is a private institution that had rarely made the manuscripts accessible to scholars or performers. Wolff, whose own research focuses on J.S. Bach and Mozart, says, "The material is very much understudied."

Understudied, but well-traveled. When the Allied air war against Germany intensified in 1942-43, many German museums, archives, libraries, and private collections stored their most valuable objects in countryside repositories for safekeeping. These were often castles and monasteries in wooded areas of no military interest--generally to the east, beyond the range of Allied bombers. The Bach materials were put away in Silesia, now part of Poland. "It was a good decision, but they miscalculated," Wolff says. Soviet soldiers reached Silesia in 1945 and seized whatever "trophy art" they found. Cultural officers of the Red Army helped identify the most valuable objects for removal. This educated advice may have saved the Bach trove from destruction. Back in the USSR, the war-trophy art was distributed to various provinces. Unresolved legal questions about its status added to the secrecy surrounding the process.

In the late 1970s, a librarian in East Berlin told Wolff of a rumor that some material from the Sing-Akademie collection had survived in the Ukraine. But, as Wolff drily observes, "Ukraine is a big country." For two decades, he wrote to conservatories and state authorities and asked Ukrainian musicians touring in the West about the materials--all without effect.

Then Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, BI '69, who directs a project on Russian and Ukrainian archives at Harvard's Ukrainian Research Institute, found a document from a Moscow archive indicating that more than 5,000 musical items had been deposited at the conservatory in Kiev. That sounded like about the right number to Wolff, but the conservatory flatly denied that they had anything. And they didn't: in 1973 the KGB, which oversaw war-trophy material, had removed the music to a state archive in Kiev, where it presumably would be under tighter government control. Yet Wolff's inquiry to that archive also proved fruitless.

Help finally arrived from Hennadii Boriak, deputy director of the Institute of Ukrainian Archaeography and Source Studies in Kiev. He found a retired librarian from the music conservatory who (unlike those on the state payroll) was willing to talk. The materials, she said, had gone to the state archive's museum for literature and art. Boriak did not learn the music's provenance, but when Wolff asked if the collection contained Bach family materials, he replied, "Yes, quite a few." Wolff applied for a visa.

Ukraine's interest in establishing good relations with the West may have smoothed the process from that point on. At the state archive, the first item that Wolff took off the shelf contained no Bach music, but, as he recalls, "When I saw the stamp of the Sing-Akademie on the volume, I realized that this was it." Perhaps he did not cry, "Eureka!" but he felt "kind of overwhelmed. I could not believe that this had finally happened." Furthermore, the materials were complete and very well preserved, and include far more--letters by Goethe, for example--than the Bach music, which constitutes only about 10 percent of the 5,000-plus items.

The future holds "a ton of interesting and exciting work" for colleagues, students, and himself, Wolff says. With funding from the Packard Humanities Institute, founded by David Packard, Ph.D. '67, microfilming of the Bach materials may begin later this year. Wolff predicts that eventually the collection will return to the Sing-Akademie, and notes that for musicologists, these documents "are opening up perspectives that are really important," particularly regarding the musical history connecting J.S. Bach with Mozart. Lastly, Wolff calls the discovery "a wonderful demonstration of what academic collaboration" can produce. "None of us individually," he notes, "would have arrived where we ended up together."

~ Craig Lambert