In 1979, a voice on the radio attracted the attention of George Scialabba ’69. It was “gentle and earnest, logical, persuasive, politically astute,” he recalls. “I was surprised to hear it was Noam Chomsky, whom I knew only as a linguist.” Scialabba (shih-lob-uh) soon read some of Chomsky’s books, including The Political Economy of Human Rights, then just out, a two-volume series that, he felt, would “set American political culture on its ear.” Yet, six months later, “the culture remained upright,” he reports. He saw no reviews of Chomsky’s work. Bemused, if not outraged, Scialabba wrote his own 3,000-word review and sent it to Eliot Fremont-Smith, literary editor of The Village Voice. Scialabba admitted that he wasn’t a writer and had no expectation of publication, but wanted to suggest the kind of serious attention Chomsky’s work merited. Fremont-Smith wrote back to disagree, telling Scialabba that he was a writer, and that the Voice would publish his essay.

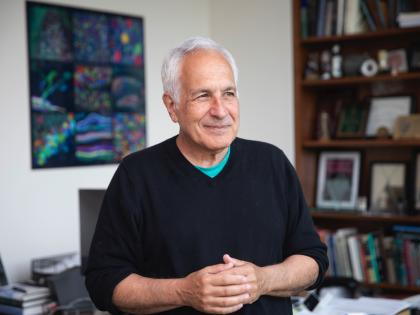

That was in 1980; more than 350 essays and book reviews later—in The Nation, The Boston Globe, Commonweal, Dissent, Grand Street, The American Conservative, The Washington Post, and dozens more—Scialabba’s credentials as a thinker and writer are well established. He publishes as a freelance critic while working a “day job” at Harvard, where he has been a staff assistant at what is now the Center for Government and International Studies since 1980.

Many of his pieces are collected in his three books, whose covers display some striking testimonials. He is “one of America’s best all-round intellects,” according to James Wood, professor of the practice of literary criticism. Social activist and writer Barbara Ehrenreich notes that “T.S. Eliot once observed that, for a literary critic, ‘the only method is to be very intelligent.’ George Scialabba raises the bar. He is not only astoundingly intelligent, he knows just about everything—history, politics, culture, and literature.”

In his newest collection, For the Republic: Political Essays (Pressed Wafer, 2013) Scialabba (www.georgescialabba.net) takes on numerous public intellectuals. In “Zippie World,” his takedown of Thomas Friedman’s 2005 bestseller The World Is Flat, he remarks at the outset that there is one quote in the middle of the text that “towers over the intellectual landscape of the rest of the book the way a mountain towers over low hills.” This quote, alas, comes not from Friedman but from Marx and Engels—their celebrated prophecy of globalization in the Communist Manifesto: “All that is solid melts into air.” Scialabba adds, “Friedman has apparently just discovered it and is ‘in awe of how incisively Marx detailed the forces that were flattening the world during the rise of the Industrial Revolution….’ ”

Soon, he deconstructs what he sees as Friedman’s naive enthusiasm for “Zippies,” young Indian employees with “a zip in the stride” and a ready embrace of technological Western corporate life. “It’s tempting to smirk at this ad-copy prose and at the rest of Friedman’s hymn to the Grand Global March of Productivity,” he writes, later observing: “That information technology might have the effect of making life, at least in some respects, less gracious, subtle, sensuous, and profound, but instead more sterile, frenetic, shallow, and routine—there is no inkling of this in The World Is Flat, indeed no evidence that Friedman could even comprehend the notion.” There have been, Scialabba says, a fair number of “people expressing reservations about the hyper-connected world,” but there are also “geeks and techno-worshippers who haven’t a clue as to what this downside might be, and Friedman is clearly one of them.”

Scialabba can accomplish a great deal with a few words and a wicked sense of humor. He notes in passing that as a young man, the neoconservative writer Irving Kristol “…became an apprentice machinist but alas, did not persevere.” He calls Gore Vidal’s Selected Essays “a kind of crème de la crème with strawberries,” quickly adding that Vidal is “perhaps best known for his raspberries.” In a piece that both praises and excoriates Christopher Hitchens, he calls the late polemicist a “compulsive name-dropper,” noting that in one short book, “the words, ‘my friend,’ followed by a distinguished name, appear dozens of times, giving the reader’s eyebrows a considerable workout.”

Reviews begin either with an offer from an editor or a proposal by Scialabba, who scrutinizes publishers’ catalogs of forthcoming books and Publishers Weekly. He begins by “setting all my physical and imaginative energies to procrastination,” which includes reading previous books by the author and “reading around” the subject in related works. “I like to make the reviews vehicles for organizing my thoughts on a topic,” he says. “I have strong opinions, but I’m too lazy and disorganized to fashion original essays, so I write reviews.” He takes notes on index cards, not in margins (“I don’t like disfiguring books”), and, like many writers, completes his essay just before deadline. In his acceptance speech for the National Book Critics Circle Citation for Excellence in Reviewing in 1992, Scialabba declared, “What I prize above all in the writers I most cherish is a certain disposition or virtue, call it disinterestedness. I mean that rare and (for me, anyway) supremely difficult ability to care more for getting things right than for winning arguments, for understanding rather than for being admired.”

Though he identifies himself as a radical, in the sense of “a Michael Harrington-type democratic socialist,” Scialabba cites Oscar Wilde and George Orwell as his real heroes—the former for his “delicious wit” and “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” and the latter for his lack of self-importance. “The literary consequence of that was Orwell’s plain-spokenness,” he says. “He made it an art.” Though Scialabba’s politics are well left of center, his ethical code is hardly unconventional. “My moral through-line,” he says, “is the Sermon on the Mount.”