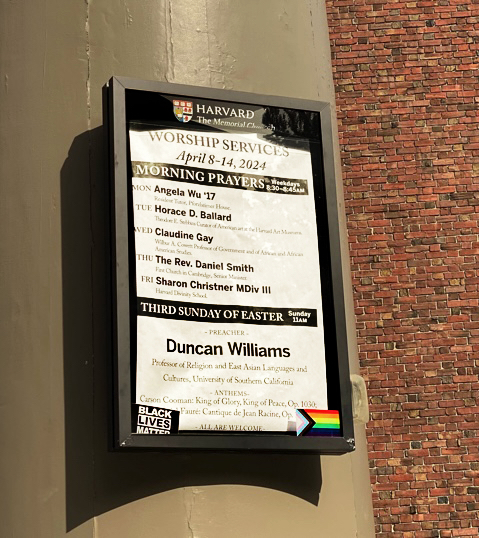

On Wednesday morning, former Harvard president Claudine Gay addressed the Harvard community publicly for the first time since her resignation. Gay spoke in Appleton Chapel as part of the daily Morning Prayers service. She recounted a story about her mother, a Haitian immigrant who came to America to work as a live-in nanny. When the family she worked for failed to live up to their promises (helping her enroll in English classes and in hopes of becoming a nurse), she slipped away and began her life anew.

When Gay was a child, she said, her mother’s story seemed like an adventure tale. Now it serves as a source of strength: “I wonder about her resilience through setbacks, about the courage to pursue a bold vision for her future despite forces intent on her diminishment, about the hope that allowed her to begin again.”

Gay also touched on new beginnings, subtly referencing two of her own: life without her mother, who died a year ago, and the end of her presidency, which ended in January. “As I stand on the threshold of a new chapter,” she said, “I miss my mother’s voice, but I find comfort in the knowledge that I am my mother’s daughter with her resilience, courage, and hope, with a soul that delights in beginnings, and that is enough to step into the unknown with confidence.”

Gay has previously shared stories about her mother, including at a Morning Prayers service last September. Then celebrating her installation as president, she said “I think of the time and effort she must have devoted to getting me on that show in the first place. And I think of her pride and her joy in her achievement—and in my achievement.”

Below is the full text of Gay’s Wednesday remarks (as published by Memorial Church):

When my mother emigrated from Haiti to the United States, she came as a live-in nanny for a family here in the Boston area. The agreement with her and with the agency that had placed her was that the family would help her enroll in English language courses as the first step in her journey to college and eventually to a nursing career. My mother arrived young and alone, but buoyed by a clear and urgent vision for her future. It was not long before she realized that the family did not share her vision. Her household responsibilities expanded. Her freedom of movement diminished. Her questions about ESL courses went unanswered. All of the assurances that had emboldened my mother to leave Haiti were swept aside in an effort to impose what felt, at best, like indentured servitude. My mother was distressed but unbowed. Over the course of several months, as she labored for this family, she quietly began making weekly trips to the post office, each time sending off a small package, small enough to fit in her purse, to an address in Brooklyn where an older sister lived.

Eventually, a day arrived when she set out for her weekly errands, carrying nothing more than her purse, and this time walked past the post office and continued on to the bus station where, heart racing and determined, she boarded a Greyhound for New York to begin again. My mother first told me this story many, many years ago and my relationship to it has changed over time. When I was young, younger, I was captivated mostly by the subterfuge and her cleverness, how she concealed from the family her plans for escape, how the family failed to notice that objects were slowly disappearing from her bedroom. What I heard was an epic adventure story and it elicited in me a mix of pride in my mother’s ingenuity and envy that my own life was devoid of drama.

As I grew older, the adventure receded as the focal narrative. I wondered instead about how she decided what to send ahead and what to leave behind. What was important to her, what mattered most for her future. I marveled at her unsentimental attachment to things and felt embarrassed by my shoe boxes full of trinkets and tchotchke. I've been thinking about this story a lot in the last few months, in part as I approached the first anniversary of my mother's death and contemplate her improbable American journey that began and ended only a few miles from here. My questions are different now. I wonder about her resilience through setbacks, about the courage to pursue a bold vision for her future despite forces intent on her diminishment, about the hope that allowed her to begin again. Where did that come from? This time, I'm left to guess at the answers.

I feel myself straining to hear my mother’s voice, light, but insistent, and always formidable. My mother’s wisdom took the form of directives. A no-nonsense, no-excuse style that bothered me as a child, but now I would welcome. How do you summon resilience, courage, and hope? How do you begin again? Just tell me. In his poem, “For a New Beginning,” John O’Donohue opens with this promise: “In out-of-the-way places of the heart where your thoughts never think to wander, this beginning has been quietly forming, waiting until you are ready to emerge.” My mother was not a storyteller. That’s more my dad. It’s because her stories were so rare that I remember this one about her first months in America so vividly, and keep coming back to it, turning it over and over in my head, mining it for lessons to comfort and guide through every chapter of my life.

Today, I understand that my mother offered the story less as entertainment than as evidence. A reminder of what lies within us in out-of-the-way places of the heart, and what may lie ahead if we dare to let go of the past and trust in the process of renewal. Though mind and body may feel unsettled by change, the soul delights in the act of starting over, even when the destination is not clear. “Unfurl yourself into the grace of beginning,” urges O’Donohue, “Awaken your spirit to adventure. Hold nothing back. Learn to find ease and risk. Soon you’ll be home in a new rhythm, for your soul senses the world that awaits you.” As I stand on the threshold of a new chapter, I miss my mother’s voice, but I find comfort in the knowledge that I am my mother’s daughter with her resilience, courage, and hope, with a soul that delights in beginnings, and that is enough to step into the unknown with confidence.