On Wednesday evening, during the Arts First festival’s opening event, Interim President Alan M. Garber paused the proceedings briefly to “acknowledge someone whose generosity of time and talent has shaped and altered forever the lives of countless students at Harvard.” He was talking about Jack Megan, director of the Office for the Arts (OFA), who will be stepping down at the end of June, after 23 years on the job. “On the first day of his final Arts First, we celebrate and thank” him, Garber said. Then, after the applause quieted, Garber turned to congratulate this year’s Harvard Arts Medal recipient, Kevin Young ’92, the prize-winning poet and director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “This is a praise song for the arts at Harvard, which taught me life,” said Young, when it was his turn at the podium. “The arts also taught me the science of the self.”

This year’s festival is special for a few reasons. Megan’s departure is one: under his leadership, which began in 2001, the OFA grew significantly, expanding its public art and performance programming, adding fellowship opportunities, opening a new ceramics studio facility, and renovating the Farkas Hall stage. Nearly 40 percent of Harvard’s 7,000 undergraduates now participate in arts programming through the OFA every year.

The 2023-24 school year also marks the OFA’s fiftieth anniversary. In recent months, the office has launched new initiatives, in line with a strategic plan that was released last August. “The OFA is on the edge of its next era,” Megan said in an interview last week. “I really see this moment as a beginning, not an ending.”

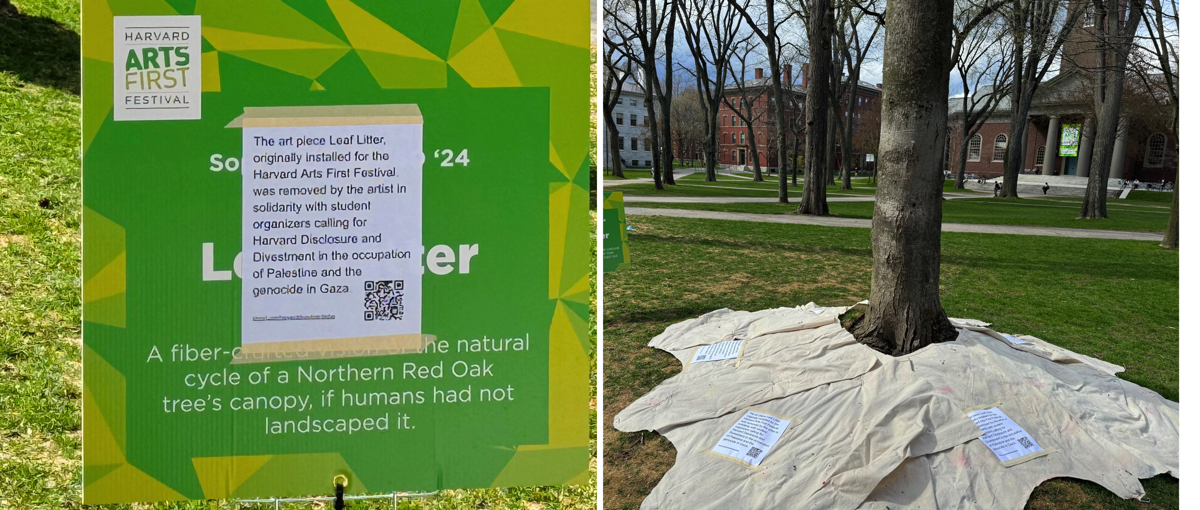

This year’s festival is the largest yet, and through this weekend, the campus will host a profusion of artistic offerings by both students and professionals: music and dance performances, theatrical productions, Lindy Hop lessons, the festival’s first-ever drag show, a pirate-themed percussion “romp,” film screenings, storytelling, singing, mural-painting, art exhibits and installations, a free-for-all performance fair, and a public art sculpture in Tercentenary Theater inspired by Japanese tea rooms. (The festival is likely to be affected by demonstrations related to the Israel-Gaza war. On Wednesday, a pro-Palestine encampment was set up in Harvard Yard by student protestors, and on Thursday one of the Arts First artists, Graduate School of Design student Sophie Chien, removed her installation, “Leaf Litter,” from the festival, “in solidarity with student organizers,” according to signs placed in the Yard.)

The OFA’s basic mission seems simple—to weave the arts into University life—but it’s also vast. Its goal is to engage students, as many of them as possible, from beginners to serious practitioners, in extracurricular programs and services that foster both art-making and art appreciation. The OFA connects students to funding and to one-on-one interactions with prominent, accomplished artists; it commissions new work from students and helps them bring their own ideas and projects to fruition; it maintains partnerships with schools and departments across the University, as well as with artists and organizations across the country and the globe. The OFA offers courses, workshops, residencies, and apprenticeships in which students work with industry professionals, both on the faculty and outside of Harvard. The First-Year Arts Program offers incoming freshmen an intensive weeklong immersion in the arts. There are programs in jazz and public art, as well as a dance center and a ceramics studio. The list of OFA-affiliated orchestras, choruses, and bands now numbers in the dozens.

“You just feel so supported,” says Julia Rooney ’11, a painter and multidisciplinary artist who decided to apply for an arts fellowship with the OFA’s help after spending her freshman summer on a mad dash through Italy as a writer-researcher for Let’s Go travel guides. “The itinerary was something like 50 cities in eight weeks,” she says. It was thrilling, but “There was no time to really process anything.” As soon as she got home, “I had this very, very strong urge to go back, but to go back as an artist.” The following summer, with fellowship funding, she returned to Italy and took things slower, developing the seeds of what would become a creative thesis, and, later, a career in the arts. “It was huge,” she says of the OFA’s support. “The money, but also the confidence you feel, that what you’re doing is valid.”

Joy Nesbitt ’21, a theatrical director and neo-soul musician, tells a similar story. “The OFA kind of forced me to take the next step as an artist,” she says. She grew up in Texas, acting and singing in high school musicals—and loving it—but arrived at Harvard with plans to study microbiology, which seemed a safer, more logical choice. Then she did the First-Year Arts Program, and it cracked open a door; as she kept working with the OFA on plays and musicals, the door opened wider. She remembers Megan and Alicia Anstead, OFA’s associate director for programming and communications (and Arts First producer), helping her and her castmates secure funding and production rights to put on God Of Carnage over Zoom during COVID-19. That play was one of three Nesbitt directed during College. While she was there, the OFA invited playwright Jeremy O. Harris to visit students, when his Tony-nominated Slave Play was on Broadway. “That was so formative for me and other black artists I was working with,” Nesbitt says, “because we could see ourselves in this person.” Previously, she hadn’t thought of art as sustainable, as “something I could make money on and live a real life.”

Equally important, she adds, was the encouragement from OFA staff members to move from acting and singing and music-directing to running her own production. “They were like, ‘If you want to direct, you could do it yourself. You could be in charge.’ Which is something I really needed to hear.” Now based in Dublin, Ireland, where she earned a 2022 M.F.A. from the Lir National Academy of Dramatic Arts, Nesbitt works as a freelance theater director, with a busy calendar. “I’m still pinching myself.”

Nesbitt’s experience points to something that Megan describes as critically important about the OFA’s programs: they exist outside the classroom. Students have room to stretch and try new things—and fail—without the worry of grades. “Learning through extracurricular artmaking can be transformational in the lives of students. Extracurricular arts—yes, they can be fun. They can be for play. But some of it is serious business. And this is where students cut their teeth, quite often, in directing, or in acting, or whatever the form is. And it’s a space in which they can do it without academic consequences.”

One of his favorite experiments involved a public art installation titled “Where Do We Go From Here?,” which was created in 2016 in response to a Harvard survey from the previous year, showing that sexual assault was widespread on campus. On display in residential Houses and then Tercentenary Theatre, the installation consisted of 14 Plexiglas and aluminum columns. Inside them, artists Delfina Sol Martinez Pandiani ’17 and Devon Guinn ’17, pasted excerpts from the report and community messages from then-President Drew Faust and Harvard College Dean Rakesh Khurana. Mirrored stickers were attached to the columns, and viewers could write their own messages on the artwork. The response from students and other University community members was enormous, Megan remembers. “The question was, whose responsibility is this?” he says. “And people were encouraged to draw their own answers on the artwork.”

Martinez Pandiani was a junior at the time, studying human evolutionary biology, and had done some mural painting but wasn’t involved in any campus arts programming. They remember attending a town hall at the OFA after the report was released and feeling, paradoxically, that it was the only space on campus, during that fraught moment, that didn’t seem performative. “It was like, we’re not just talking in the abstract world, we’re talking about getting our hands dirty,” Martinez Pandiani recalls. “And then we actually got our hands dirty.” After Harvard, they went on to a Ph.D. in computer science and work in the digital humanities, at the intersection of cultural data analysis and AI, but that artistic experience—and experiment—remains important. “Jack became invested, and we were able to put this artwork in Harvard Yard, and having that connection with the institutional part of Harvard allowed us to do something powerful.”

Similar artistic experimentation is everywhere, Megan says. Kathy King, director of OFA’s Ceramics Program and Visual Arts Initiatives, sees it at the ceramics studio on the Allston campus. Classes there routinely draw two or three times the maximum possible enrollment. “It’s non-credit, so students don’t have the same stress,” she says. “They’re in a different physical space down here, and in a different mental space too.” Elizabeth Epsen, who leads the OFA Dance Program, notes that the dance center offers one-week residencies to train student groups to mount their own dance performances. As far as skill levels, she says, “It’s a real mix—most of us grow up having some dance as part of our lives….There is a contingent of students who come from a ballet, jazz, tap background, and they’re either looking to continue their training, or they want to branch out.”

There are so many stories like this, of students who discovered something about themselves, or about the arts—or whose life trajectories were altered—through a connection with the OFA. But there are many other students who come to Harvard already on an artistic trajectory, and a serious one. Conductor and composer Benjamin Wenzelberg ’21 started at the College after eight years in Juilliard’s pre-college program and another eight as a soloist and chorister in the Metropolitan Opera’s children’s chorus. He always knew he wanted to be a professional musician. For his senior thesis (he concentrated in English and music), he composed an opera, Nighttown, based on James Joyce’s Ulysses, which premiered at Lowell House Opera in 2022. It won the American Prize in Composition as well as the Morton Gould Composer Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (that was his second time winning the latter—his first was for an opera he wrote in 2014, when he was still in high school). After Harvard, he moved to the Netherlands, where he is finishing up his final year of the National Master in Orchestral Conducting, a two-year master’s program offered jointly by the Conservatorium van Amsterdam and the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague.

And yet, Wenzelberg says, the OFA was crucial to his artistic development at Harvard, subsidizing private singing lessons, providing a fellowship to the Gstaad Conducting Academy in Switzerland, and facilitating “a ton” of opportunities to conduct performances and hone his skills. His master’s program normally isn’t open to people without a formal conducting degree, he notes, but his extracurricular experience at Harvard helped overcome that limitation. When the Harvard College Opera was rehearsing The Magic Flute in 2019, with Wenzelberg as music director, the OFA invited in singer Morris Robinson, a bass with the Metropolitan Opera who is famous for his Magic Flute performance. “Morris did a master class with us,” Wenzelberg says. “I still keep in touch with him.” When COVID-19 hit and students were sent home, Wenzelberg and other musicians in the Harvard College Opera decided to attempt a virtual performance together. “And the OFA shipped microphones all over the world—multiple continents—to make sure that when people were recording, it would sound consistent,” Wenzelberg says. “That’s integrity for art-making.”

Accommodating the full range, from an expert like Wenzelberg to a novice making a first foray into the arts, is a bedrock part of the OFA’s mission. “Everybody who has an interest in the arts, whatever their experience, should have the opportunity to explore,” Megan says. “That shouldn’t be the exclusive domain of people who got the education and had the opportunities…. It shouldn’t be a place where you have to know the code in order to get in. We should make visible the pathways.”

But that can be an uneasy balance, says Federico Cortese, a senior lecturer in music and the longtime conductor of the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra. He worries sometimes about allowing the arts to become a “comfortable sofa” of soft, easy ideas. “The arts have been given the task of being flag bearers of ideas…but the fact that the arts are a vessel for ideas is both true, but dangerous,” he says. “The arts are vessels of uncomfortable ideas, not widely shared ideas—something we disagree with but that makes us think or makes us see things we didn’t see before or didn’t want to admit.” Grappling with the arts in this way is rigorous work; it requires thousands of hours of practice and immense intellectual and emotional engagement. “This is a very different function from exposure to the arts, or simply becoming familiar with our art histories,” he says. And yet: “All of these things are important.” It’s a tension he thinks may be unresolvable—the way tensions often are in works of art. “So we’ll just keep juggling and juggling this many balls and try to make sure that no one falls on the ground.”

That tension is sometimes apparent in the OFA’s strategic plan, released last August, after a year’s worth of research and interviews with some 240 stakeholders. The report made several recommendations, including calling for more opportunities in the visual arts (OFA programs tend heavily toward the performing arts), more arts programming in the Houses (an initiative is already under way to open up exhibit and performing space), and stronger career pathways for students who want to pursue the arts professionally (another initiative already under way).

There is also an emphasis on equity and inclusion. The report makes note of some changes in the student body that Megan has noticed, too, since he joined the office more than 20 years ago. Back then, 35 percent of Harvard undergraduates identified themselves as black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, or Native Hawaiian; today that number is 60 percent. Also 20 years ago, only five percent of undergraduates were first-generation college students; today 15 percent are. “It’s just a much, much more diverse student body,” Megan says, which underlines the urgency of making sure the arts are available to everyone on campus. “Plus, students are facing issues that are new and different: social media and digital everything, the fact that there's so many more ways of making art, issues of identity, gender, sexuality, issues of mental health. All of these things are rising up, and so it was time to ask, how does the OFA need to evolve?”

One of the OFA’s more enthusiastic staff members is Dara Badon ’22, assistant director of the First-Year Arts Program. As an undergraduate, Badon joined the Harvard University Band, participated in the dance and arts enrichment program CityStep, and worked as a student production assistant in the OFA. She was a participant, and later a student leader, in the First-Year Arts Program. But where she grew up outside of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the arts were not well very funded and not always accessible. “Still, I knew I loved the arts,” she says. “And in the ways I could, I had an arts background.” She was in the middle school band and attended a community dance studio. When she got to Harvard, she studied history and literature and structured her extracurricular life around the arts. As a senior, she was awarded the OFA’s Levi Arts Prize for efforts and energies devoted to arts administration and the art-making community. “I think the OFA gave me the vocabulary to identify a career in the arts,” she says, “and to realize that it might be something non-traditional, not conventional. I know more now than I used to. I see the multidimensionality.”

That kind of experience is part of what Megan and the OFA are aiming for. “The extracurricular arts scene is so important to literally thousands of students,” he says. “And the message we should take from this report is: we should take this seriously. … How should we think about it as an opportunity to advance the College mission of intellectual, social and personal transformation? Clearly, this kind of artistic engagement does lead to intellectual exploration. You can’t do Waiting for Godot, or Shakespeare, or Tristan and Isolde, without understanding something very deep about the ideas behind [them].”

Talking this way, Megan is reminded of the first time he attended an Arts First festival, back when he was deciding whether to take the OFA job. Coming to campus, he was skeptical. “I thought, ‘Harvard doesn’t take the arts seriously. Why would I want to be here?’” he recalls. But then he arrived, and wandering from stage to stage, he saw students from all over the world presenting their work. The range was broad: a Shostakovich trio, an excerpt from Martha Graham’s Lamentation, 15 friends dancing for the joy of it, an a cappella troupe, an electric guitarist jamming with a guy on a hammer dulcimer.

And at each stage, he found audiences cheering on their classmates. “It was a revelation, the idea that students were effectively saying, ‘I see you, I honor you, I’m here to celebrate you,’” Megan says. “And it just made me realize that this is really important work.” He came away profoundly moved. “What I discovered is, whether or not Harvard takes the arts seriously, the students take it seriously,” he says. At this week’s Art Fest, which feels both like a beginning and an end, that part remains unchanged.