Dr. James Muller, a young Harvard cardiologist in the 1970s, was standing in a parking lot outside Boston’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital when he first imagined Russian and American doctors joining forces to oppose nuclear weapons. It was an idea as improbable as it was urgent: that physicians on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain could work together to cool the nuclear arms race.

The organization that grew from that moment—International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW)—was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985 and helped reduce the world’s nuclear arsenal from more than 50,000 warheads to about 13,000 today. Along the way, the IPPNW facilitated one of the more surprising diplomatic side stories of the Cold War era, in which a young real estate developer named Donald Trump, deeply anxious about the threat of nuclear war, turned to the IPPNW—and met with Muller’s mentor Bernard Lown in New York—for help in reaching Mikhail Gorbachev.

Decades later, Muller believes that story holds lessons for today’s debates about the threat of nuclear weapons, the role of universities, and the freedom of scholars to tackle issues far beyond their laboratories. He credits Harvard’s tradition of academic freedom for giving him and colleagues like Lown, Eric Chivian, and Helen Caldicott the space—and the credibility—to organize a global movement that influenced world leaders, defied official U.S. government policy, and reshaped the public understanding of nuclear risk.

In this conversation, Muller, who remains a senior lecturer at Harvard Medical School, retraces that remarkable journey—from a flash of inspiration in a hospital parking lot, to secret meetings with Russian doctors and heads of state, to an unexpected connection with a future U.S. president—and shares why he believes the power of open, independent inquiry still matters today. (This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

—The Editors

Harvard Magazine: Can you take us back to the moment when you first heard that Donald Trump, then a real estate developer, wanted the IPPNW’s help to meet Mikhail Gorbachev? What did that reveal about Trump’s thinking on nuclear weapons at the time?

James Muller: I believe that President Trump sincerely wants zero nuclear weapons. I don’t agree with his methods, but I do agree with that goal. Back in 1986, he was already anxious about the threat. He asked for help, and Bernard Lown, my mentor, met with him in New York and ultimately connected him with Gorbachev. It’s quite interesting: [Ronald] Reagan said he was for zero, [Jimmy] Carter said it while building more warheads, but none really proposed practical abolition. Ironically, the only president who offered a real solution was [Harry S.] Truman, who, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, proposed that all nuclear weapons be eliminated under United Nations control. That “Truman-Baruch proposal” still makes sense today.

HM: What was your understanding, then and now, of why Trump, a businessman, cared so deeply about nuclear disarmament?

JM: I think it goes back to his uncle, John Trump, who was a brilliant physicist at MIT. Trump often says that his uncle taught him about the dangers of nuclear weapons. So, he grew up with that awareness. Of course, there’s also the less flattering take: the nuclear issue offers a kind of ultimate power, and Trump gravitates toward power. But I take him at his word on this—he wants zero nuclear weapons, which is something I respect.

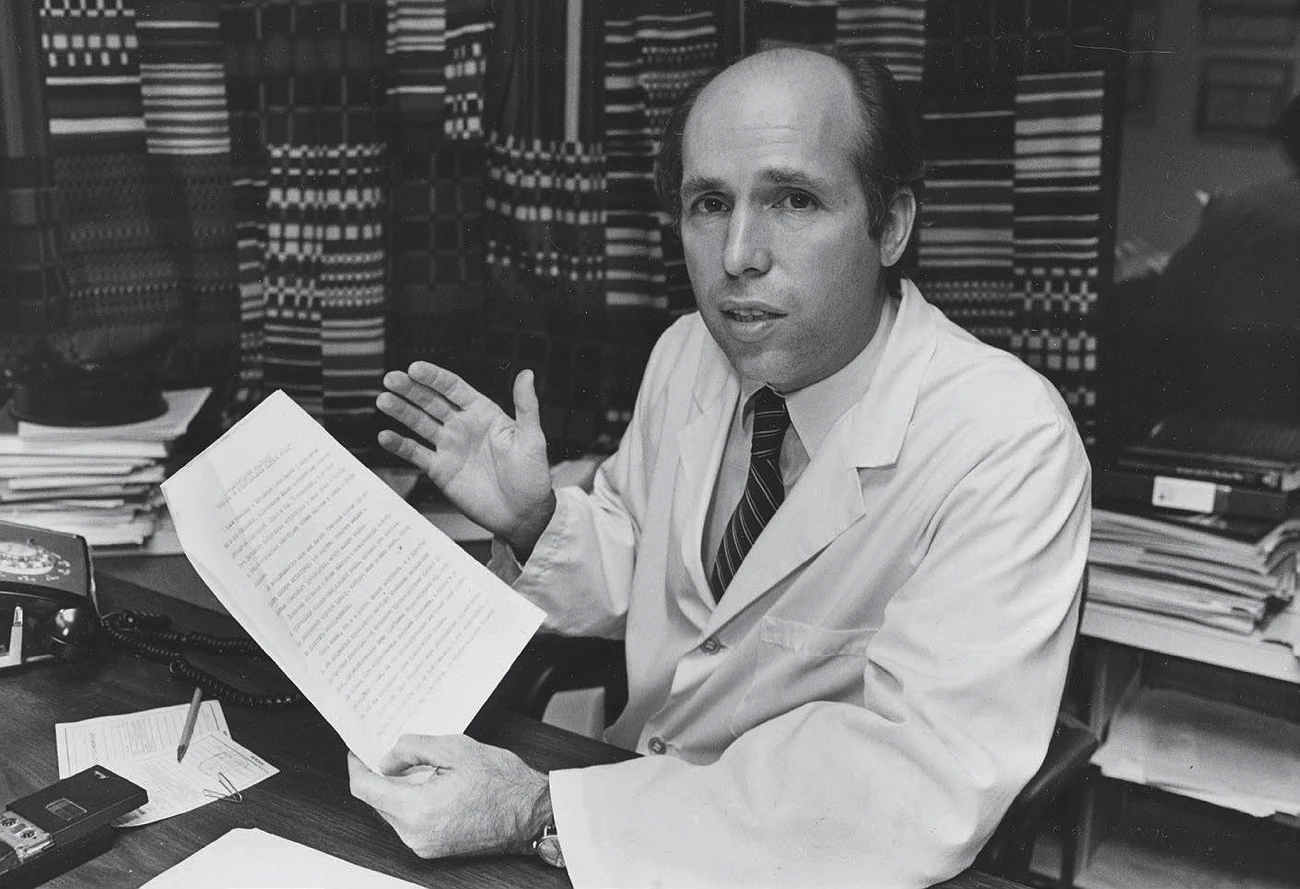

HM: You’ve described the spark for organizing American and Russian doctors against nuclear weapons happening in a Brigham Hospital parking lot. What did that moment look like?

JM: I was walking between my office and the hospital, thinking about patients I’d treated—especially burn victims. I’d lived in Moscow in 1967 and again in 1975, and I knew how deeply the Russian people opposed war. It struck me: maybe our Russian colleagues hated nuclear weapons as much as we did. I shared the idea with Bernard Lown, who wrote to his contacts in Moscow. It took some time, but eventually Dr. Yevgeniy Chazov, Brezhnev’s doctor and my mentor when I worked in Moscow, agreed to join forces. That was the beginning of IPPNW.

HM: How did your time studying in Moscow and learning Russian—notable, given the recent focus on international students—shape your belief that Russian doctors would want to collaborate?

JM: It was pivotal. I studied Russian at Notre Dame because my father said, “They put Sputnik up there—study Russian!” Then, while studying medicine at Johns Hopkins, I spent six months at a Moscow hospital doing cardiac research. When I would walk around the streets, I would not see men of a certain age, or I’d see people with war injuries. I saw how the Russian people, having lost 20 million in World War II, deeply feared war. When I was there in Red Square, I’d watch missiles roll by aimed at my own family back home. It drove home the urgency of finding ways to build bridges.

HM: And that relationship with Chazov—did it help?

JM: Tremendously. Chazov was my teacher. I translated his book on heart attacks into English. I also wrote an article about Chazov being one of the first people to treat heart attacks with clot-dissolving drugs. So, he knew all of that. When we first met to launch IPPNW, the situation was tense—Russia had invaded Afghanistan, and many American doctors wanted nothing to do with Soviet colleagues. But we agreed: this would be a single-issue effort. No politics—just the shared goal of preventing nuclear war.

HM: Why did you believe that physicians could bridge the Cold War divide?

JM: Doctors everywhere want the same thing: money spent on health, not weapons. We saw it as a public health issue—who else was speaking for the billions who’d be annihilated in a nuclear war? The physicists who built the bombs told us: “Forget politicians. We’ve been whispering in their ear for decades, and they keep building more nuclear weapons—go straight to the public.” And so, we did. We spoke plainly about burns, crush injuries, radiation sickness. Helen Caldicott, then a pediatrician at Harvard Children’s Hospital, gave unforgettable talks—one-third of her audience would walk out committed to fighting nuclear weapons.

HM: Did you ever think your work might run into trouble with Harvard or the government? You never received any pushback from a professor, a dean, or an administrator?

JM: Never. The dean of the medical school at the time wrote a letter in support of us. The Harvard environment was marvelous. Academic freedom was like air—you didn’t think about it because it was just there. Harvard’s stature was invaluable. When we wrote to other medical schools, they picked up the phone because we were from Harvard. The New England Journal of Medicine published what we wrote. The Countway Library even has an exhibit on IPPNW—including my handwritten script for a broadcast that reached 100 million Russians.

HM: Looking back, what concrete changes came from IPPNW’s work?

JM: The most obvious is the reduction of the world’s nuclear stockpile from 50,000 to about 13,000 warheads. That wasn’t just treaties—it was also public pressure. Jimmy Carter was promoting the MX missile—he’d been a nuclear submarine engineer and was in favor of building more nuclear weapons—and there was a plan to put nuclear weapons into Europe, which is why all the European doctors came to our first meeting in Washington, D.C. Jonas Salk, the polio vaccine pioneer, also joined our first big meeting in 1981. We helped advise The Day After, the 1983 TV movie that forced people to imagine what nuclear war really meant. There was a march of a million people in New York City, I think in ’83.

And the Nobel Prize? Well, that was quite a story. During the press conference, a Russian reporter collapsed. I gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, Jennifer Leaning from the Harvard School of Public Health performed an intubation on the floor, all on live TV. Americans and Russians working together, and we saved this person’s life—it was a metaphor for what we were trying to do for the world.

HM: You’ve described the nuclear threat as a “dragon” that disappears and reappears every few decades. Why does it feel urgent again now?

JM: I do think it’s a dragon that lives in the jungle and is only visible every once in a while. It was visible in the ’80s. It was visible in 1946 after Hiroshima and Nagasaki—that’s why Truman proposed abolition. Today, it’s visible again because of AI, Ukraine, North Korea, and the fragile nature of global cooperation. Add to that climate change, which indirectly fuels conflicts between nuclear-armed states. The threat is persistent, and it only takes one mistake. Annie Jacobsen’s book on nuclear war imagines how easily things could escalate. Helen Caldicott used to say that the only way we’ll ever get on the right track, unfortunately, is for another nuclear bomb to be set off and kill a million people. Then maybe humanity will summon the will to do what needs to be done. [Annie Jacobsen’s Nuclear War: A Scenario was first published in 2024.]

HM: Do you think Helen is right about that?

JM: That’s a tough question. I hope Helen is not right. This is a question for humanity. How smart are we? How good is our collective will to do the right thing? Can we see that this is such a horrible threat that we have to find a multinational solution at a time when the world is heading towards nationalism?

HM: What lessons does your story hold for younger scientists and physicians about the power—and fragility—of academic freedom?

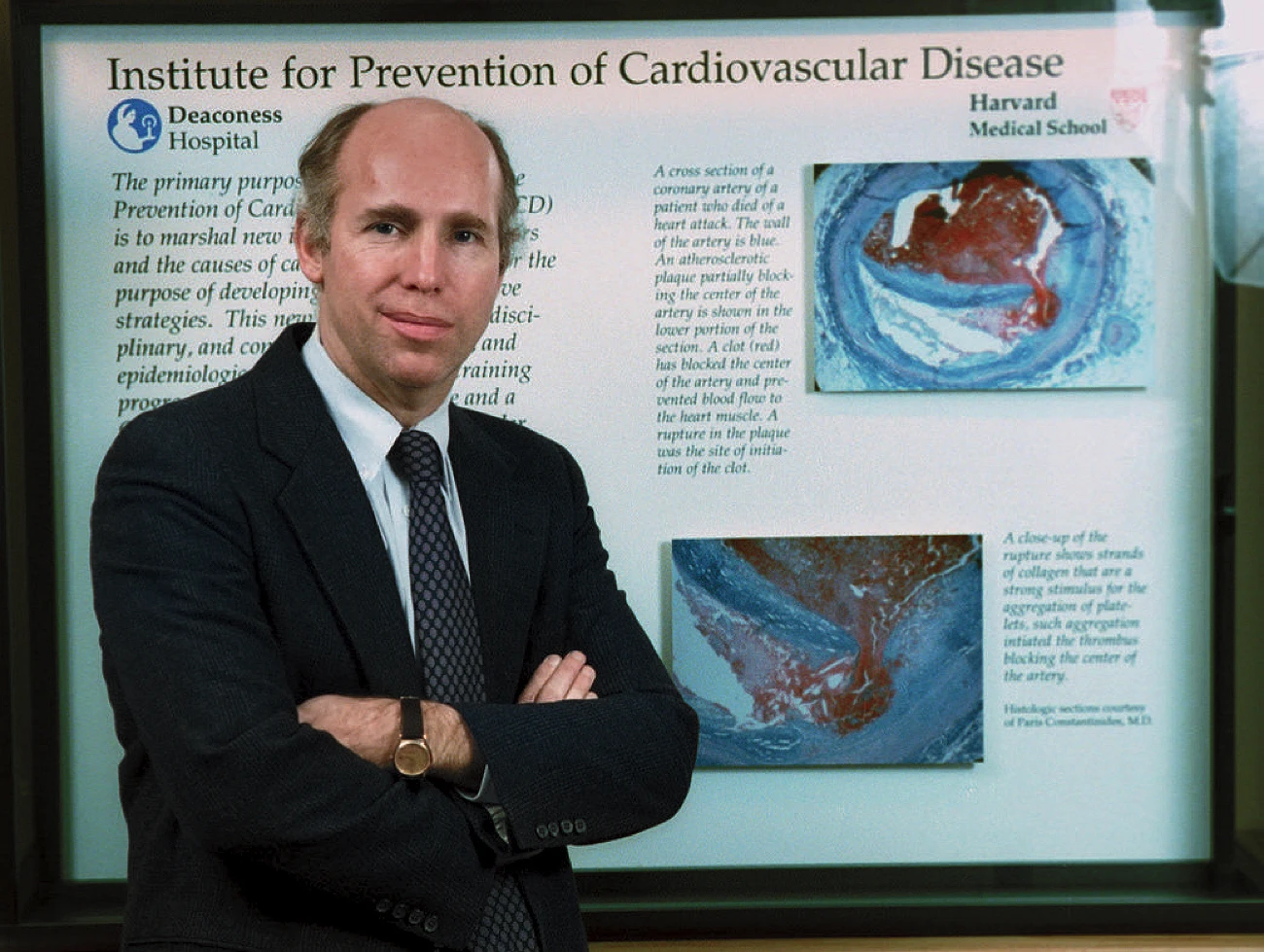

JM: First, the freedom to oppose government policy. No one needed 25,000 nuclear weapons, yet we had them. Second, the freedom to bring in international students. My research on heart attacks [Muller discovered that clotting is the reason more heart attacks occur in the morning] relied on fellows from Australia, Japan, Germany. Third, the funding from the government to pursue independent science. These conditions allowed us to challenge the arms race, and to make medical discoveries—like the “vulnerable plaque” that can trigger a heart attack, a term that ironically comes from my arguments with the Pentagon about “vulnerable” missile silos.

HM: If you could say one thing to both Harvard and Trump today about the connection between your anti-nuclear work and Harvard’s role, what would it be?

JM: I prefer not to call it anti-nuclear; Jonas Salk taught us to frame it positively—this is work for the prevention of nuclear war. I’d say this: the academic freedom that Harvard defends so strongly has helped move the world closer to Trump’s stated goal—zero nuclear weapons. That freedom has global consequences. Harvard’s motto is Veritas—truth—and in this age of misinformation, it’s needed more than ever.

HM: Do you think we’re capable of getting to zero?

JM: The only real solution remains the same as Truman proposed in 1946: global abolition under United Nations control. It’s not the U.S. or Russia alone—it must be the world acting together. It sounds idealistic, but so did the idea of American and Russian doctors working side by side when I first stood in that parking lot.