Nick Cato has always liked working with his hands. Growing up in a small town just outside Hillsborough, North Carolina, he says, “I was always outside, messing around, building stuff, climbing trees.” He enjoyed reading, but he struggled in school, where he was expected to learn by sitting still, watching, and listening. “I’m a hands-on learner,” Cato says. “Being in a classroom was not very stimulating. I found my mind wandering and had trouble focusing from an early age.”

Cato thought about going to college, but his grades weren’t good enough for the schools he was interested in, he says. The summer before his senior year of high school, he interned at a water purification company and found that he liked the tactile nature of the work. Trade school seemed like the logical next step. But when the pandemic began during the spring of his senior year, he never applied: “It kind of broke that momentum and drive I had,” he says. After graduation, he bounced between different jobs—first as a FedEx package handler, then back at the water purification company, then as an auto repair technician.

He was at that last job when he came across a TikTok about ADTC, a school in Ohio that trains people in skilled trades. In the video, a man explained that ADTC was offering a six-week training program in HVAC—heating, ventilation, and air conditioning—in Indianapolis, Indiana. The school would fly students out, put them up in a hotel, and connect them with employers. As for cost? The entire program would be free for students, with future employers covering tuition.

Today, Cato has worked as an HVAC technician for more than a year. He makes $22 an hour—more than he’s ever made. He has benefits, such as paid time off, and his coworkers and clients treat him with respect, unlike in his past service jobs. Plus, there are clear pathways for growth: new skills to learn, management and leadership roles that come with wage gains. “This is the best job I’ve ever had by far,” he says. “I learn a ridiculous amount every day.”

Before ADTC, Cato had fallen through the cracks of America’s traditional education system. He’s not the only one: for decades, the share of college degrees earned by men has been declining. In 1972, the year Title IX was passed to promote gender equality in higher education, men earned 56.4 percent of all bachelor’s degrees, while women earned 43.6 percent—a 13-point gap. By 2019, there was a 15-point difference—in the other direction, with women earning about 58 percent of all bachelor’s degrees. The pandemic accelerated that trend: from 2019 to 2020, male first-time college enrollment dropped by 5.1 percent, compared to less than 1 percent for women.

That gender disparity starts before college—and has consequences long after. By many metrics, American girls outperform boys in primary and secondary school, graduating at higher rates and with better grades. Since 1979, most men’s real wages have fallen, while most women’s have risen, and an increasing share of “prime-age men”—those between ages 25 and 54—has given up looking for work. Men die “deaths of despair” from suicide, drugs, or alcohol at nearly three times the rate of women. And often, those hit hardest by these trends are working-class, men of color, or both.

Researchers and policymakers focused on gender equality have long—rightly—directed their efforts toward expanding opportunities for women, who continue to face inequities in earnings, responsibility for childcare, and representation in leadership roles and certain careers. But since the middle of the last century, as women’s rights have advanced rapidly and the economy has shifted toward automation and globalization, many men have struggled to adapt to changing labor markets and educational settings—yet far fewer resources are directed toward addressing those challenges.

Some programs, like ADTC, are beginning to change that. In 2020, the nonprofit Social Finance began working with the school; since then, more than 1,100 people have graduated, achieving a median wage gain of over $17,000, says Tracy Palandjian ’93, M.B.A. ’97, Social Finance cofounder and CEO (and a member of the Harvard Corporation).

More than 90 percent of those graduates are men, many of whom say they struggled with traditional education but thrived in ADTC’s focused, hands-on lessons. That aligns with research showing that boys tend to struggle more than girls in conventional classrooms—and that career-oriented training works especially well for them.

To scale such solutions and develop new ones, researchers say, it’s first necessary to understand the challenges facing boys and men. At Harvard and elsewhere, scholars are increasingly turning their attention to doing just that. “If you diagnose what the problems are,” says professor of management practice Joseph Fuller, “very often, the solutions will present themselves.”

The Heart of American Economic Losses

In 2015, by most measures, the American economy was on the upswing. Unemployment was nearing pre-recession levels; that year, median household income rose for the first time since 2007. But as chair of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, Jason Furman was troubled by an indicator that still hadn’t recovered: the employment rate of men aged 25 to 54, or “prime-age men.”

To try to understand why, Furman examined the change in their employment rate during the last few decades. That’s when he realized it had been falling steadily since the 1950s. “I don’t know why I hadn’t been attuned to that issue before then, because it’s just incredibly striking and important,” says the Aetna professor of the practice of economic policy.

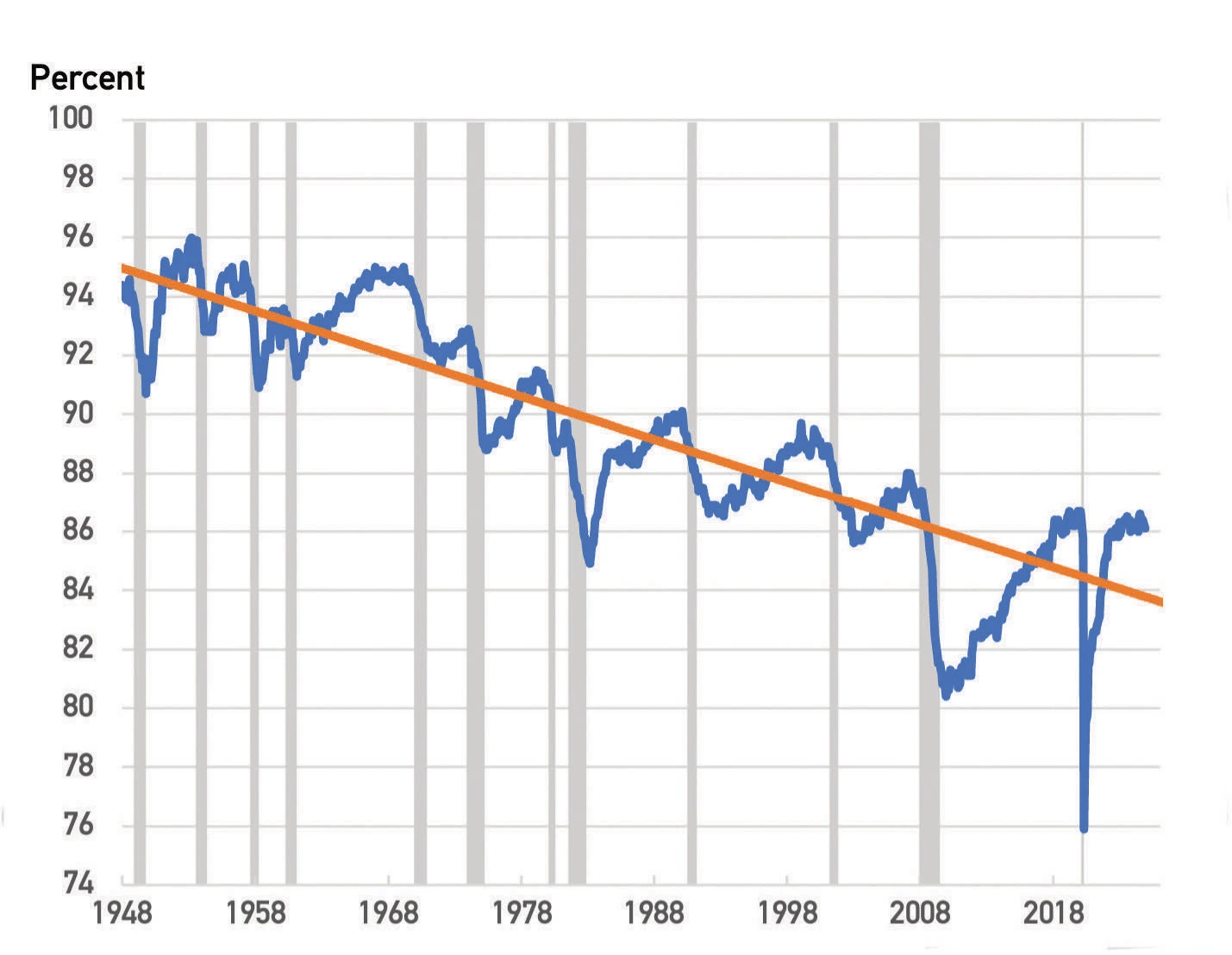

In 2016, 88 percent of prime-age men were either working or actively looking for work—down from 91.5 percent in January 2007, and from the peak of 98 percent in the 1950s. At first, some wondered whether this trend might be positive: perhaps as more women joined the workforce, men had more flexibility to stay home and perform unpaid labor like childcare or housework.

But the data told a different story. Among men who’d dropped out of the workforce, fewer than a quarter had a working spouse—a figure that had declined over the decades. Time-use surveys showed they didn’t do significantly more childcare or chores than working men. The trend spanned the prime-age range, suggesting it wasn’t driven by youth disaffection or early retirement. What seemed to unite the men was education: they were disproportionately non-college graduates.

Since peaking at around 96 percent in the 1950's, the employment rate of men between ages 25 and 54 has steadily declined

source: Calculations based on bureau of labor statistics, macrobond/courtesy of Jason Furman

Though the trend was decades old, Furman was among the first to identify and describe it. Such work is the first step toward making policy, he says: “You want facts. You want explanations of those facts. And then you want solutions.” In 2015, not even the first step toward addressing male joblessness had been completed.

That’s not unusual when trying to understand the challenges facing boys and men, says Richard Reeves, whose 2022 book Of Boys and Men brought these issues to many policymakers’ attention. In 2023, Reeves founded the American Institute for Boys and Men (AIBM) to encourage more research, like Furman’s, focused on describing and analyzing these trends. Furman and Ackman professor of public economics Raj Chetty—both of whom have studied men and the labor market—serve on the AIBM’s advisory council.

The AIBM has an unofficial motto: “Keep it boring.” Reeves explains, “Too much of the discussion about gender just gets caught up in the froth of the culture war”—think pieces about the Barbie movie or Mark Zuckerberg’s sartorial choices. When he founded the AIBM, “what was lacking wasn’t more opinion pieces or talking heads. What was lacking was good, solid research asking: what is actually going on? What do we know about what’s being done to try to address that? Have we evaluated those things, and are they replicable?”

The failure to engage with men’s struggles has left a vacuum, Reeves argues—one now filled by populist politicians and “manosphere” influencers. The same year Furman flagged the rise in male joblessness, Donald Trump launched his first presidential campaign, promising to restore a lost version of America where men could be men: breadwinners, protectors. He won that election with an historic 24-point lead among men, and the counties that swung furthest to Trump, compared to Mitt Romney’s performance in 2012, were those with the most deaths of despair—and the sharpest declines in employment.

The election made clear that certain parts of the country were struggling more than others. Just how much became clearer in 2018, when three Harvard economists—Eliot University Professor Lawrence H. Summers, Glimp professor of economics Edward Glaeser, and then-doctoral student Benjamin Austin—mapped the geography of male joblessness (see “Fixing America’s Heartland,” September-October 2018, p. 8). The phenomenon was concentrated in what they called the “eastern heartland,” the stretch of states from Mississippi to Michigan.

The level of variation they uncovered was astonishing. In 2016, just 5 percent of men in Alexandria, Virginia (a wealthy suburb of Washington, D.C.), were not employed. In Flint, Michigan, that figure was 51 percent. The costs extend far beyond lost paychecks, Glaeser says, because “for men, the correlation between life satisfaction and not working is just enormous.” For those aged 25 to 54, not having a job strongly predicts unhappiness, suicide, divorce, and opioid use—more than it does for unemployed women, or even men in low-wage jobs.

By now, the narrative of the eastern heartland’s economic decline has become familiar: amid globalization and automation, the region hemorrhaged manufacturing jobs. So, the researchers recommended subsidizing work in struggling areas to spur employment. Policies enabling low-income workers to take home more of their paychecks at no cost to employers—such as expanding the earned income tax credit—could help achieve that goal.

In 2015, Furman believed the main reason for male joblessness was simple: not enough jobs. Now, he’s not so sure. When the pandemic began in 2020, women’s employment fell more than men’s, since they were overrepresented in the hard-hit service industry and took on more childcare. But today, prime-age women’s employment rate has surpassed pre-pandemic levels. Prime-age men’s employment continues to lag—despite a “huge number of job openings” through 2021 and 2022, Furman says.

“Even if there are help wanted signs in their town, why are they not signing up for those jobs?”

To understand why, Furman thinks research should further examine regional variability in employment opportunities. There are also questions for sociologists and psychologists to explore, he says: “Even if there are help wanted signs in their town, why are they not signing up for those jobs?”

The Origins of Disadvantage

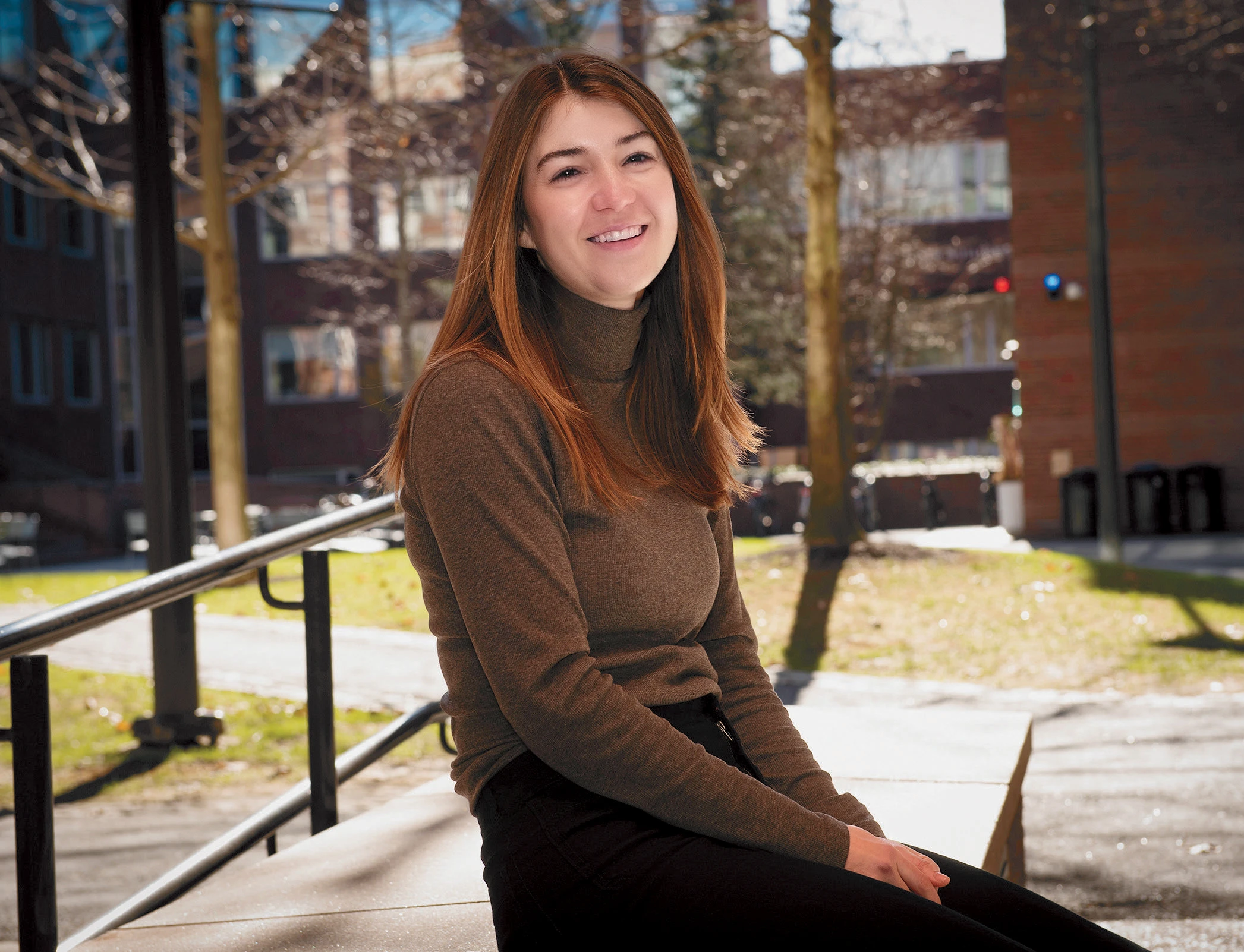

As an undergraduate studying public policy at the University of Chicago, Clare Suter, Ph.D. ’28, was used to navigating spaces where men dominate. Women made up just 25 percent of that university’s tenure-track faculty, a 2010 report found. Many of her classmates were headed for high-wage careers such as finance and law, where women struggle to make it to the top. From economics classes, she knew that men work more, earn more, and advance further in their careers—and she assumed that was true across the income distribution.

Then, she read a 2016 paper by Raj Chetty and colleagues about how childhood environments affect boys and girls differently. Among children raised in the poorest households, the researchers found, boys were less likely than girls to work as adults. The gap was wider for boys raised by single parents, and those who grew up in high-poverty, high-minority neighborhoods.

“I realized that there was this whole discussion that wasn’t happening—that if you zoom out of the top of the income distribution, by a lot of metrics, the gender gap is totally reversed,” says Suter, now an economics graduate student at Harvard.

Suter was one of many shaken by Chetty’s findings. In 2018, Chetty cofounded the research institute Opportunity Insights; his work has shown how childhood poverty and neighborhood disadvantage profoundly shape adult outcomes—with boys appearing especially vulnerable to these effects. “Boys growing up are super sensitive to their environments,” Suter says, “and that may explain different outcomes in adulthood.”

What drives that heightened sensitivity is unclear. Crime may play a role: boys are far more likely than girls to interact with the criminal justice system, and disadvantaged neighborhoods might heighten that risk. But research suggests that boys are more sensitive to their environments even in early childhood, with disadvantaged neighborhoods seeming to harm their kindergarten readiness more than girls’. “There’s just not a lot of good evidence for what explains this trend,” Suter says, but understanding it is key to designing early-childhood interventions to support boys.

For black boys, race compounds economic disadvantage. While black and white girls from similar economic backgrounds achieve comparable incomes as adults, black boys earn far less than their white counterparts, Chetty and colleagues reported in 2018. That means that income inequality between black and white Americans is driven entirely by the outcomes of men and boys. Disparities persist even for boys raised at the top of the income ladder: black men from wealthy households are employed at lower rates than white men raised in poverty. As Reeves writes in Of Boys and Men, black men face particular challenges—from higher rates of school discipline to higher rates of incarceration—“not in spite of their gender, but because of it.”

The income gap between black and white boys remained even when they were raised in families with similar incomes, structures, education levels, and accumulated wealth. That suggests the cause is structural, not based on individual family characteristics. This is another area where further research could provide insight, Suter says, including on a hypothesis called the “role model effect.” In the few neighborhoods where poor black boys did well, many had fathers at home—and the presence of those fathers was a strong predictor of the neighborhood boys’ success regardless of whether their own fathers lived with them.

That means male role models might play a significant role in shaping boys’ trajectories—whether as fathers, teachers, coaches, or others. This spring, Suter was awarded a fellowship from the AIBM to research questions related to the well-being of boys and men. Among her planned projects is an analysis of male teachers’ influence on boys. She plans to examine immediate effects on factors like grades and attendance. But she’s especially interested in longer-term outcomes: “Do boys who have a male teacher stay out of the criminal justice system in a way that other boys don’t?”

The Impact on Women

In November 2024, Donald Trump won the popular vote for the first time, doubling his support from black men compared to 2020 and winning nearly half the votes of Latino men. He also increased his standing among young men, flipping a 15-point loss among that demographic in 2020 to a 14-point lead in 2024.

Suter wasn’t surprised. “With the way that young men voted, I think people are coming to see that there’s something happening—and if we continue ignoring it, it’s not likely to get any better,” she says. It’s important to address those challenges for their own sake. But the stakes also extend further, she explains: “Men struggling affects everyone—their spouses, their sisters, their children.”

Opportunity Insights research backs this up. Black and white girls from similar households earn comparable incomes as adults, according to the 2018 paper. Yet “black women continue to have substantially lower levels of household income than white women,” the authors wrote, “both because they are less likely to be married and because black men earn less than white men.” The result is a self-perpetuating cycle of inequality, as black children continue to grow up in poorer households.

The decline in male college enrollment also affects women’s marriage patterns—though not in the way some might expect. During the last few years, much news coverage has speculated that the gender gap in higher education will hurt the marriage prospects of college-educated women, who prefer to marry partners who are at least equally educated. “We were interested in seeing if this is actually true,” says Joseph Winkelmann, Ph.D. ’26, a graduate student in public policy who has studied marriage trends.

It turns out that it’s not. During the last half-century, marriage rates for college-educated women have remained remarkably stable: by age 45, 78 percent of those born in 1930 were married, compared to 71 percent of those born in 1980. But for women without a college degree, marriage rates plummeted: from 79 percent to 52 percent.

How did college-educated women’s marriage rates remain so stable, even as similarly educated men become scarcer? Since 1975, economic outcomes for men without college degrees have declined overall. But there was variation within that group: some have seen their real wages rise, while most have experienced a significant drop. College-educated women tend to marry the former group—leaving fewer economically stable partners for women without degrees. As a result, non-college-educated women are marrying less—but still having children, meaning that those children grow up in households with fewer resources.

The findings undercut the popular gender-war narrative, which often centers on high-income women freezing eggs and forgoing relationships. The data show that, in fact, working-class women face the steepest marriage challenges. “When we’re thinking about the broader research agenda of equality of opportunity and improving economic prospects for kids,” Winkelmann says, “this clearly suggests that focusing on the economic outcomes of men can help us.” Part of the solution involves encouraging more men to attend college, he says—but policymakers should also think more broadly about improving the lives of men who don’t.

Hands-On Learning

In 2005, a group of anonymous donors in Kalamazoo, Michigan, pledged to fully fund state-college tuition for every student educated in the city’s public schools. The program had a remarkable impact, boosting postsecondary completion rates by 12 percentage points. But researchers at the Upjohn Institute found that this effect appeared to manifest only among women.

That isn’t an outlier. Across the United States, numerous programs designed to boost academic achievement (including a mentoring initiative in New Hampshire, scholarships in Arkansas and Georgia, and “Project READS” in North Carolina) seem to help female students while having little to no impact on their male counterparts, Reeves writes.

“It’s depressing that, over and over again, research finds that when you do blank, it helps girls,” Furman says, “but we’re not quite as sure how much it helps boys.” Given that gap, he says, it’s crucial to measure programs’ differential effects by gender—and to promote those that benefit boys and men, too.

In that context, the fact that more than 90 percent of ADTC graduates are men is a feature of the program, not a bug. Expanding such workforce training can help address men’s labor market challenges, says Joseph Fuller, who leads the Project on Workforce, a collaboration among the Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard Business School, and the Harvard Graduate School of Education that seeks to improve postsecondary education to enhance economic mobility.

“The skills development system is serving its purpose less and less effectively in the United States,” he says. Even as college is touted as the key to economic mobility, many well-paying jobs don’t require a bachelor’s degree—but quality training opportunities for those roles are scarce. The consequence is decreasing workforce participation: a “perilous” trend, Fuller says, that has hit men particularly hard.

The Project on Workforce has partnered with job training programs across the country to expand access to skills development, helping more people secure stable, well-paying jobs. ADTC accomplishes this by asking employers what skills they look for, then tailoring their education offerings to the responses. According to cofounder and CEO Timothy Spurlock, the program offers job-ready training in trades such as truck engine repair, truck body repair, and HVAC in just weeks—compared to the months or years it would take at a community college or technical school.

The program also shifts the cost and risk of education away from students. In some instances, a student’s employer covers the cost of their education if they stay for a set period—in Cato’s case, four years. And in a new model developed with Social Finance, students pay for their schooling only if they secure a job with a minimum income. “We’re trying to interrogate who pays, who benefits, who should bear the risk, and reallocate incentives,” Tracy Palandjian says.

Hands-on education isn’t limited to workforce training. Career and technical education (CTE) can also help to engage male students in high school and college. A 2023 MIT study, for example, examined a system of 16 technical high schools in Connecticut, which educate about 7 percent of the state’s high school students. Boys in these schools were 10 percentage points more likely to graduate than boys in traditional schools—and their average quarterly earnings were 32 percent higher. (There was no equivalent effect for girls.) “Very few labor market interventions could hope to achieve that,” Suter says, and expanding such opportunities is a promising strategy to address gender gaps in education.

“What Would My Life Look Like?”

In 2002, as a first-grade teacher on Milwaukee’s north side, Joseph Derrick Nelson was assigned a group of students labeled as “at risk.” Their kindergarten teachers had warned him: “This one can’t keep his hands to himself. This one talks constantly. This one can’t sit still.” His job was to enforce strict discipline—keep them quiet, seated, on task.

But as Nelson got to know his students—mostly black and Latino boys—he saw that they were “so much more than these stories,” he says. Like many boys, they sometimes struggled to sit still and appeared less focused than their female classmates. But instead of seeing that disengagement as a cue to teach differently, their teachers interpreted it as defiance and a lack of discipline. And the more these boys heard that narrative about themselves, the more likely they were to believe it.

Early experiences like this shape the struggles men face later in life, argues Niobe Way, Ed.D. ’94, a developmental psychology professor at New York University. Her research shows that while boys form emotionally intimate friendships in childhood, those bonds weaken as they get older—not because they lose the need for close connections, but because they’re told masculinity means dominance, stoicism, and independence.

Losing those relationships has staggering lifetime costs. A 2023 report from the organization Equimundo found that two-thirds of men believed that “no one really knows [them]”; in a 2021 survey, one in seven men said they had no close friends. Such social isolation increases the risk of heart attack, stroke, depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline. It also partly explains why men’s suicide rate is four times that of women, says Pierce professor of psychology Matthew Nock. “Men are less likely to reach out for care, less well connected to others, and more likely to use more lethal means for suicide attempts,” he explains.

Stereotypes about masculinity also limit men’s educational and work opportunities, Way says. The expectation that men should be breadwinners, for example, may contribute to their reluctance to spend time in degree programs that require general education in addition to career training. And the belief that men belong in physical or technical fields—not professions centered on people—might explain their declining presence in what Reeves calls “HEAL” jobs: healthcare, education, administration, and literacy. From 1980 to 2019, the proportion of women in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) careers rose from 13 percent to 27 percent, Reeves writes in Of Boys and Men. For men in HEAL professions, it decreased from 35 percent to 26 percent.

Helping boys and men think more broadly about their roles in society would have practical economic benefits.

Helping boys and men think more broadly about their roles in society would have practical economic benefits: HEAL jobs are among the fastest growing in the United States. By 2030, the country will need 400,000 more nurses and nurse practitioners; in a 2021 survey, two-thirds of school districts reported teacher shortages. “One solution is almost never mentioned,” Reeves writes—recruiting more men to join these fields.

That can happen at the college level, with scholarships and internships to attract men to HEAL professions. But it can also start earlier, Way says, by expanding boys’ understanding of who they can become. To that end, Way, Nelson, and colleagues have developed the Listening with Curiosity Project, a 26-lesson curriculum integrated into middle and high school classes. The program involves students interviewing classmates and family members, then presenting about those conversations. In a 2023 study, students who participated in the program reported improved listening skills, empathy, and social connection; both students and teachers reported better classroom climate and academic engagement.

“You can foster curiosity in young people, and when you do, it’s linked to better mental health. It’s linked to better social health. It’s linked to academic engagement,” Way says. This process also helps boys realize they’re more than the stereotypes they encounter, adds Nelson, a professor of education and black studies at Swarthmore and a fellow with the Boys’ Club of New York. “When the world mirrors back at them something that isn’t who they are, they’re better positioned to resist and hold onto themselves,” he says. The impact extends beyond the economic benefits of getting more men into HEAL professions: it can also help boys and men reimagine their roles in society after an era of rapid change has displaced traditional scripts.

Nick Cato, the HVAC technician trained by ADTC, didn’t always dislike school. From an early age, he loved reading books and analyzing poems—work that helped him write his own music on the guitar. But those passions weren’t always nurtured in school, where he often had trouble concentrating. He especially struggled with math, which felt impossibly abstract. Once, in fifth grade, he tucked a novel into his math textbook so he could read during class. His teacher berated him and emptied his desk in front of the classroom to make sure he wasn’t hiding anything else.

Afterwards, he had a thought: “I would never do that when I’m a teacher.” It was a habit he’d had for as long as he could remember: whenever teachers did something he liked or disliked, he’d reflect on what he would do similarly or differently. “I always had this notion of ‘when I’m a teacher,’” he says. “But I thought it was just some stupid thought that would go away.” But lately, as he’s talked with friends and family, he’s considered what might have happened if he’d taken that thought more seriously. “Especially recently, I’ve thought about that and wondered, what—what would my life look like,” he says, “had I gone to college for something like that? You know?”