I

n a taxi bound for the Pierre Hotel on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Thomas Kane rehearsed the pitch he’d memorized to persuade the world’s richest man to fund a radical new approach to education reform.

Ordinarily, Kane’s speech is slow and deliberate, punctuated by measured pauses. The Gale professor of economics and education is careful to avoid overreach, demarcating the known clearly from the unknown, avoiding any suggestion of causation when two variables are merely correlated. But on the morning of October 20, 2007, Kane knew his time with Bill Gates ’77, LL.D. ’07, was limited, and he wanted a tight case for why understanding teacher effectiveness was the key to improving schools.

“For 30 years, we’ve known that some teachers are simply more effective at raising student achievement than others, and that paper qualifications tell us little about who those most effective teachers are going to be,” Kane said in Gates’s suite, over a table crowded with bottles of Diet Coke. “And, yet, in our human resource policy, we’ve acted like just the opposite were true: we’ve put all of our effort into raising certification requirements.” The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), passed five years earlier, had attempted to improve teacher quality by focusing on degrees, state licensure, and standardized tests for educators—all poor indicators of teachers’ skills in the classroom.

In front of Gates was a heavily marked-up copy of a 2006 Brookings Institution paper, reporting an analysis by Kane and colleagues of data from 150,000 students in 9,400 Los Angeles classrooms from 2000 to 2003. The researchers found a striking pattern: teachers who succeeded in raising students’ test scores one year did so consistently—and there was little correlation between this success and certification. The impacts on student achievement were “massive,” they wrote: on average, students taught by a top-quartile teacher gained five percentile points relative to students with similar baseline scores and demographic characteristics, while those assigned to a bottom-quartile teacher lost five points.

In education, “The conventional wisdom has not been evolving. We’ve been having the same debates over and over and over.”

At the meeting, as Kane advocated for further research on the subject, he was not promoting a particular intervention in schooling, a field rife with ideas for improvement. Instead, he articulated a new way to approach education reform—one centered around measuring and tracking the effectiveness of interventions. This may sound obvious: other fields, from medicine to business, rely on systems for testing new ideas and adjusting best practices accordingly. “That doesn’t happen in education. And that’s why the conventional wisdom has not been evolving,” Kane says now. “We’ve been having the same debates over and over and over.”

The consequences are clear. Since the 1983 federal report “A Nation at Risk” warned of “a rising tide of mediocrity” in American education, federal and state governments have spent billions trying to improve student outcomes. Yet American teenagers’ performance in reading and math has remained stagnant since 2000—and disparities between high- and low-performing students are growing. Pandemic learning losses have exacerbated these challenges: on a 2023 administration of an international math test, American fourth graders’ scores dropped 18 points compared to 2019, and eighth graders dropped 27 points.

Kane has dedicated his career to addressing this crisis by helping school leaders and policymakers test ideas for reform. This was the challenge Gates and Kane discussed in New York. Existing research made it clear that some teachers helped students score higher on standardized tests. But how could they confirm those scores aligned with student achievement measured in other ways? And how might scholars define and measure what made an effective teacher? The answers could transform schools—enabling them to reward the most successful teachers, move them where they were most needed, and help others follow their lead.

Kane’s preparation for the meeting apparently paid off: the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation committed $60 million to answering these questions, aiming to inform the teacher evaluation policies that states were developing at the time.

It wasn’t Kane’s first time at the intersection of philanthropy, policy, and classrooms. As an education policy researcher—and now, as the faculty director of Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research (CEPR)—his career has placed him at the center of fierce debates about issues ranging from the NCLB to charter schools to pandemic learning loss. Throughout, he has remained steadfast in his belief that evidence—not ideology—should guide education reform. “And I say that because I know most things don’t work,” he explains. “I just can’t tell you, until we do the study, which things work and which don’t.”

Growing up in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Kane was “completely obsessed with blocks and Legos and Erector Sets,” he recalls—figuring out how different pieces fit together and how to fill in gaps. In school, this affinity for puzzles and problem-solving drew him to math and science, but he wasn’t sure how those interests might turn into a profession. Neither parent was a college graduate, he says, “and I didn’t have a very sophisticated understanding of different careers.”

New possibilities emerged when he enrolled as an undergraduate at the University of Notre Dame. He took an introductory economics class, thinking he might major in business. Instead, he realized “you could use math to try to understand important social problems,” he says. His senior year, a professor recommended that he apply to work at Mathematica Policy Research, an institute dedicated to reducing inequality; the experience confirmed that he wanted to pursue policy research as a career.

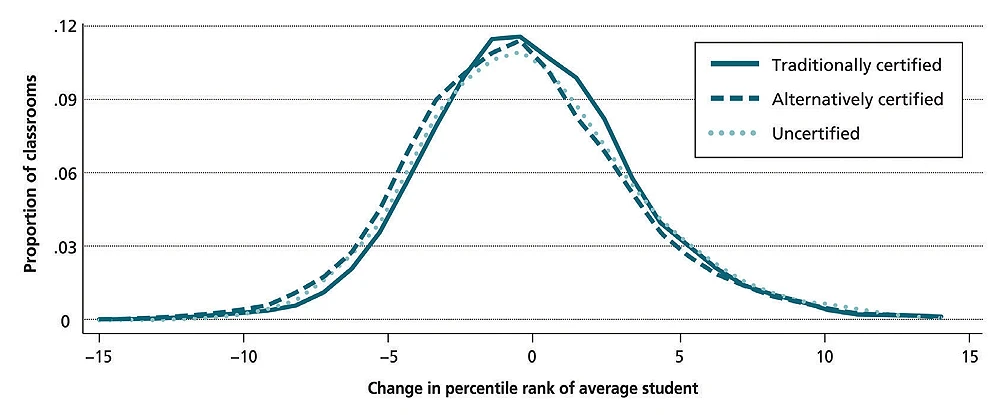

In a 2006 Brookings Institution paper, Kane and colleagues Douglas Staiger and Robert Gordon found that teacher certification had little impact on student performance. Student outcomes varied widely within each certification group, suggesting that teachers’ effectiveness mattered more than their formal credentials. | source: Robert Gordon, Thomas J. Kane and Douglas O. Staiger, “Identifying Effective Teachers Using Performance on the Job,” Hamilton Project Discussion Paper 2006-01, Brookings Institution, April 2006.

Kane began a master’s in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) in 1985, then his doctoral studies in 1988. At first, he focused on welfare reform and other issues related to “economics” in the traditional sense. Then, President Derek Bok asked David Ellwood, Kane’s mentor, if he had a student who could help him analyze a worrying trend: a decline in African American college enrollment in the early 1980s. Ellwood recommended Kane—and the topic eventually became the focus of his dissertation.

Though the project diverged from his previous work, it offered the opportunity to do what he enjoyed most about economics research: assembling blocks of data like Legos, filling in gaps, and “finding surprises.” Using federal population surveys, provided at the time on magnetic tapes, he analyzed attendance trends, then merged those data with records on tuition costs at public colleges and universities. He found that rising costs were correlated with declining college enrollment—and that the correlation was stronger for African American and Latino students than white students.

As Kane pursued his doctorate, economists were becoming aware of a growing gap in earnings between college and high school graduates, reflecting globalization and automation. In 1980, the median weekly earnings of a college graduate were 43 percent higher than those of a high school graduate; by 1992, the premium had risen to 71 percent. (At the end of 2024, that figure was around 62 percent.)

Kane had experienced firsthand the life-changing potential of higher education: without the opportunities he received at Notre Dame, he says, “I am confident I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now.” And the data increasingly showed that college was nearly essential for upward mobility. Education policy, in other words, now was an economics problem in the traditional sense, with huge effects on lifetime earnings, job benefits, health outcomes, and more.

Kane started to think about teacher effectiveness in the late 1990s, during his days as an HKS assistant professor. His office was next to that of Douglas Staiger, a fellow assistant professor who studied healthcare: how the performances of individual doctors shaped patient outcomes and hospital productivity.

One day, Kane walked into Staiger’s office and asked if there wasn’t a parallel problem to be studied in education: how teacher performance affected student and school outcomes. “He came in and started talking about that,” remembers Staiger, now an economics professor at Dartmouth, “and we’ve been working on that pretty much nonstop for more than 25 years.”

At the time, standardized testing wasn’t federally mandated, leaving states to decide whether and how to implement such exams. Many opted out, making it difficult to compare achievement across districts—or even among classrooms within the same school. But North Carolina did require standardized tests at the state level, so Kane and Staiger focused their analysis there.

Between 1994 and 1999, the state achieved impressive gains: the proportion of students proficient in reading and math increased between 2 and 5 percent each year. But on a school level, Kane and Staiger found, the gains were much more volatile. Progress by an individual school one year was often offset by loss the next.

This kind of volatility was typical in statistical analysis: smaller sample sizes are more prone to fluctuations than larger ones. At the time, the median American elementary school had 68 students per grade; a few motivated or disruptive students could skew results. (In a 2001 New York Times op-ed, Kane and Staiger outlined this research, leading Congress to revise the NCLB. The original law had required schools to achieve a 1 percent annual increase in the percentage of students proficient in reading and math—or face penalties such as restructuring. Kane and Staiger wrote that, between 1994 and 1999, 98 percent of schools in North Carolina and Texas, another successful state, would have failed to meet this standard at least once.)

But at the classroom level, where Kane and Staiger expected to see even greater volatility given the smaller sample size, they found the opposite. Teachers whose students’ scores increased in one year achieved success consistently; those whose students’ performance decreased continued to perform poorly. Kane’s initial hunch was confirmed: it seemed that teachers were a key variable in student success.

They knew this wasn’t definitive proof, however. What if some teachers were consistently assigned more or less motivated students? To answer this question, Kane and Staiger expanded their study to the Los Angeles Unified School District, which agreed to randomize student assignments to teachers. Even with random assignment of what might have been particularly motivated or disengaged students, the pattern persisted—forming the basis for the Brookings Institution paper that eventually reached Bill Gates.

After the meeting between Gates and Kane in 2007, the Gates Foundation agreed to fund the research in 2008. Then, in the spring of 2009, President Barack Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which funded a competitive grant program called Race to the Top. States competing for grants were scored partly on how they revamped their performance-based evaluations of teacher effectiveness. This spurred the researchers into action, as they aimed to publish the results of the Measures of Effective Teaching (MET) project by 2013. “We wanted to generate results quickly enough,” Kane explains, “to inform how states were redesigning their teacher-evaluation systems.”

As they devised their study, they faced a major challenge: standardized test scores weren’t necessarily a reflection of student achievement. What if teachers were simply teaching to the test or focusing narrowly on test-taking strategies? To address this concern, researchers administered assessments designed to test “higher-order thinking,” including math word problems and English short-answer questions.

They also expanded their research beyond traditional teacher evaluations, which typically involved principals observing from the back of the classroom—a process that offered limited opportunities for improvement. Video, the researchers reasoned, would enable teachers to see their own habits and how students reacted, allowing them to make changes. In addition to exams and videos, they developed student surveys to gather more insights into teacher performance.

At the time, teachers’ unions were receptive to the study, Kane says, seeing it as a way to expand teacher evaluations beyond standardized test scores. Three thousand teachers across six districts—Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Dallas, Denver, Hillsborough (Florida), Memphis, and New York City—volunteered to participate, and data were collected over two years. During the first year, the researchers used student surveys, classroom observations, and state test results to predict teachers’ likely impact on their next group of students. In the second year, the researchers randomly assigned students to teachers to compare actual outcomes with their predictions.

In the end, the MET project confirmed the hypothesis that teacher effectiveness was an important variable in student success. Gains on standardized tests were mirrored by results on more open-ended assessments, showing that teachers weren’t merely teaching to the test (though their impacts on open-ended assessments were about two-thirds as large as on standardized tests). And the measures of effectiveness from the first year—observations, student surveys, and state test scores—accurately identified teachers who produced higher student achievement and predicted the extent of those gains. This suggested that schools could combine different sources of data to provide specific feedback to teachers. They could also reward the most effective ones—and, controversially, fire the least effective.

As teacher evaluation reforms became more popular, however, teachers’ unions began to resist implementation, wary of decisions to deny tenure or dismiss teachers. Some districts that did implement evaluation protocols—including Washington, D.C., and Chicago—achieved impressive test score gains in most grades and subjects. But others—including, in another Gates Foundation study, Hillsborough, Memphis, and Pittsburgh—reported no impact on student achievement. (One explanation is that cities surrounded by suburbs had a larger pool of teachers to replace underperforming ones, while large districts surrounded by rural areas struggled with limited staffing options.)

Today, teacher evaluation remains contentious—and CEPR has begun to look for other areas where evidence can move the debate. In 2014, researchers at the center, led by Murphy professor in education Heather Hill and CEPR associate director of mathematics teaching Samantha Booth, developed Mathematical Quality of Instruction (MQI) coaching. The program relies on a rubric that analyzes math teaching, turning abstract concepts like “student engagement” into specific, actionable goals, such as encouraging students to describe their answers using mathematical language.

Teachers record videos of their lessons, share them with coaches, and review them together. “The teacher walks through the rubric with you,” explains Tammy Tucker, a former elementary and middle school teacher and principal in West Virginia trained in MQI coaching. Thanks to video feedback—which allows teachers to see how students react to their lessons—“the classrooms are more student-centered,” Tucker says. “The students are doing the thinking, they’re doing the talking.”

Khethiwe Hudson, an assistant principal in Arlington County Public Schools, outside Washington, D.C., recalls working with a teacher who struggled to improve based on written and verbal feedback. When he finally watched videos of himself, however, “He couldn’t believe the things he was doing,” Hudson says. “I saw an incredible turnaround.”

“Which is more important: what the right reading curriculum is, or whether the Treasury should issue five-year bonds or 10-year bonds?”

In 2005, Kane’s research caught the attention of Harvard’s president, Lawrence H. Summers—who had been Kane’s public finance professor during graduate school. Summers himself had studied public finance and labor economics, the bases of his academic and public service careers. But as Harvard’s leader, he recalls, he began to wonder, “Which is more important: what the right reading curriculum is, or whether the Treasury should issue five-year bonds or 10-year bonds?”

“I thought getting the right reading curriculum for three million students each year was much more important than the precise maturity structure of the Treasury debt,” he continues. “And yet, because it was financial, there was so much more expertise to draw on with respect to debt maturity, than with respect to kids learning to read.”

Summers and Kane discussed founding a research center to provide expertise for education agencies and policymakers. This research was made possible by a major shift in education policy brought about by the NCLB, which mandated that states implement standardized testing for students in grades four through eight. “The states and districts were drowning in test-score data,” Kane says, “and yet they didn’t really have the resources to study it.”

In 2006, Summers dedicated funds from his discretionary presidential account to found CEPR, which today comprises 14 researchers and about 50 staff dedicated to improving educational outcomes through data. “I was so excited by the kind of thing that I thought was necessary—moving beyond arguing about which curriculum worked, to actually being able to find out the answer,” Summers says. “It was some of the most satisfying work I did as president.”

After the MET project, researchers at CEPR have sought to use data to make progress in other areas. In Massachusetts, for example, charter schools have consistently outperformed others on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS)—prompting debates over whether this success results from practices unique to charter schools. For equity, Massachusetts state law requires charter schools to hold lotteries to select students when they are oversubscribed. Critics argued, however, that higher-achieving students were simply more likely to apply, while struggling students were more likely to be expelled.

In 2009, CEPR partnered with economists at MIT to explore this question. Charter schools agreed to release their lists of lottery outcomes, and researchers merged them with state test scores. They found that students randomly accepted to charter schools scored significantly higher on the math and English MCAS than those who were rejected—suggesting that the schools weren’t simply attracting higher-achieving applicants.

The research shed light on a longstanding question in education: “How much of a difference can a school make without changing somebody’s family or neighborhood?” Kane says. The charter school study proved that schools could have a significant impact. That information didn’t settle debates about whether charters diverted resources from other public schools. But it did provide evidence that charter schools were doing something that contributed to their success—and that other schools could learn from.

That insight, combined with his work on teacher effectiveness, led Kane in the early 2010s to explore a new avenue for school improvement. Education scholars have long known that new teachers tend to struggle with student achievement in their first year but vastly improve in their second. “One hypothesis is that during the first year, one of the main things teachers are learning is how to manage a classroom,” Kane says. “There’s very little in day-to-day experience that would teach you how to get 25 kids to pay attention.”

One charter school that Kane worked with had developed a six-week training program on classroom management for new teachers. He reached out to the Boston Public Schools district and asked if it would randomize a subset of the system’s new teachers to receive similar training, so researchers could compare their student achievement gains with those of teachers who didn’t receive the training. CEPR had funding to pay for the project, but ultimately couldn’t obtain the necessary lists of new teacher hires. “It really seems like we should know the answer to this question—with six weeks of training, can you make someone look like a second- or third-year teacher?” Kane says. But even when experiments are in place, it’s “not always possible” to persuade stakeholders to engage.

When Aimee Rogstad Guidera, M.P.P. ’95, became Virginia’s Secretary of Education in 2022, she faced a state “in crisis,” she says. During the pandemic, Virginia experienced some of the nation’s worst drops in reading and math scores. Fourth-grade math students, who had ranked second in the United States in 2019, fell to twentieth three years later; in reading, their standing fell from seventh to thirty-third. “I need help,” she recalls telling Kane on a phone call early in her tenure. “What is the data telling us? What should we be doing?”

Since the pandemic’s inception, Kane had been studying achievement losses and the widening inequities caused by school closures. Standardized tests provided insights into how districts performed relative to one another within the same state. But because each state used a different test, comparing performance among them was difficult. And even within individual states, test scores themselves provided little insight into how much students lost compared to their past performance.

To overcome these challenges, CEPR launched the “Education Recovery Scorecard” in partnership with scholars at Stanford and Dartmouth. Researchers—including Kane, Staiger, and Stanford education professor Sean Reardon, Ed.D. ’97—developed a method to convert state test results to a national scale by comparing them with scores from the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP), a biennial test for fourth- and eighth-graders. The resulting analysis exposed disparities masked by statewide trends. Across Virginia, for instance, student achievement dropped by 84 percent of a grade level in math and 60 percent of a grade level in reading from 2019 to 2022. But in two of the state’s poorest districts, Richmond and Roanoke, students lost more than a full grade in both subjects. At the same time, CEPR found that high-dosage tutoring was the most cost-effective intervention for rapid recovery from such losses.

Those insights helped Virginia allocate $418 million to address learning loss in September 2023: 70 percent for high-dosage tutoring, 20 percent for the Virginia Literacy Act (which funded new literacy curricula and professional development for educators), and 10 percent for combating chronic absenteeism. The state’s chronic absenteeism rate dropped from 20 percent in 2022-23 to 16 percent in 2023-24. And during the 2023-24 school year, Richmond Public Schools saw improvements in state test scores across all subject areas, with passage rates in science and writing increasing by 10 points.

Despite such recoveries, many students remain behind—and over the next few years, Kane says he doesn’t expect to see any major federal initiatives in K-12 education “except maybe a big push for vouchers, or tax credits, for private schools.” For now, it’s up to the states to lead reform—but they risk repeating past mistakes and sparking polarized debates if they don’t test their initiatives and collect data.

To avoid this, CEPR has begun work on “States Leading States,” a project that assigns experts in data analysis to work with state education agencies, helping them learn how to measure new policies’ efficacy. The first topic to be examined is “science of reading” reforms (see “A Right Way to Read?” September-October 2024, page 23). During the past five years, more than 40 states have passed legislation about how reading is taught—with interventions ranging from new curricula to coaching to holding back third-graders who aren’t proficient.

Such steps have prompted a fierce debate about which measures are effective—and many new curricula and practices, Kane warns, are touted as “evidence-based” but lack supporting data. By studying student outcomes in states that have taken different approaches, he says, “We can try to answer the question of: Is just switching curriculum enough? Is switching curriculum and requiring teachers to go through different kinds of training enough? How much of a difference does coaching make? We’re trying to determine how much of a difference each of these things makes and then trying to spread the ones that are effective.”

On deck are analyses of efforts to address absenteeism and cell phone use in schools. “Rather than spending the next decade wondering whether cell phone bans had an impact,” Kane says, “we could be answering that question and trying to build a consensus earlier.”

“In the absence of data on absenteeism or reading achievement, we’re more likely to

be fighting about culture-war issues.”

He feels a new sense of urgency about this work at a time when education has become a battleground for broader partisan divides. “Whatever your view on the culture-war issues, I think everybody agrees we need to help teach students to read, and we need to lower absenteeism,” Kane says. “And in the absence of data on absenteeism or reading achievement, we’re more likely to be fighting about culture-war issues.”

This article has been updated to name Sean Reardon, Ed.D. ’97, as a member of the Education Recovery Scorecard team.

This article previously misstated that Thomas Kane started his master’s in public policy in 1986; in fact, he started it in 1985.

This article previously listed the districts participating in the MET project as New York City, Tampa, Memphis, Charlotte Mecklenburg, Hillsborough (Florida), and Pittsburgh. The correct districts are Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Dallas, Denver, Hillsborough (Florida), Memphis, and New York City.