High above the Earth, in orbits crowded with satellites and debris, a silent traffic crisis is unfolding. With thousands of discarded and broken human objects whizzing around the planet at blistering speeds, the risk of catastrophic collisions is rising—and the people who best understand what exists beyond our atmosphere are growing concerned. Among them is astronomer Jonathan McDowell, who has worked at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics for 37 years.

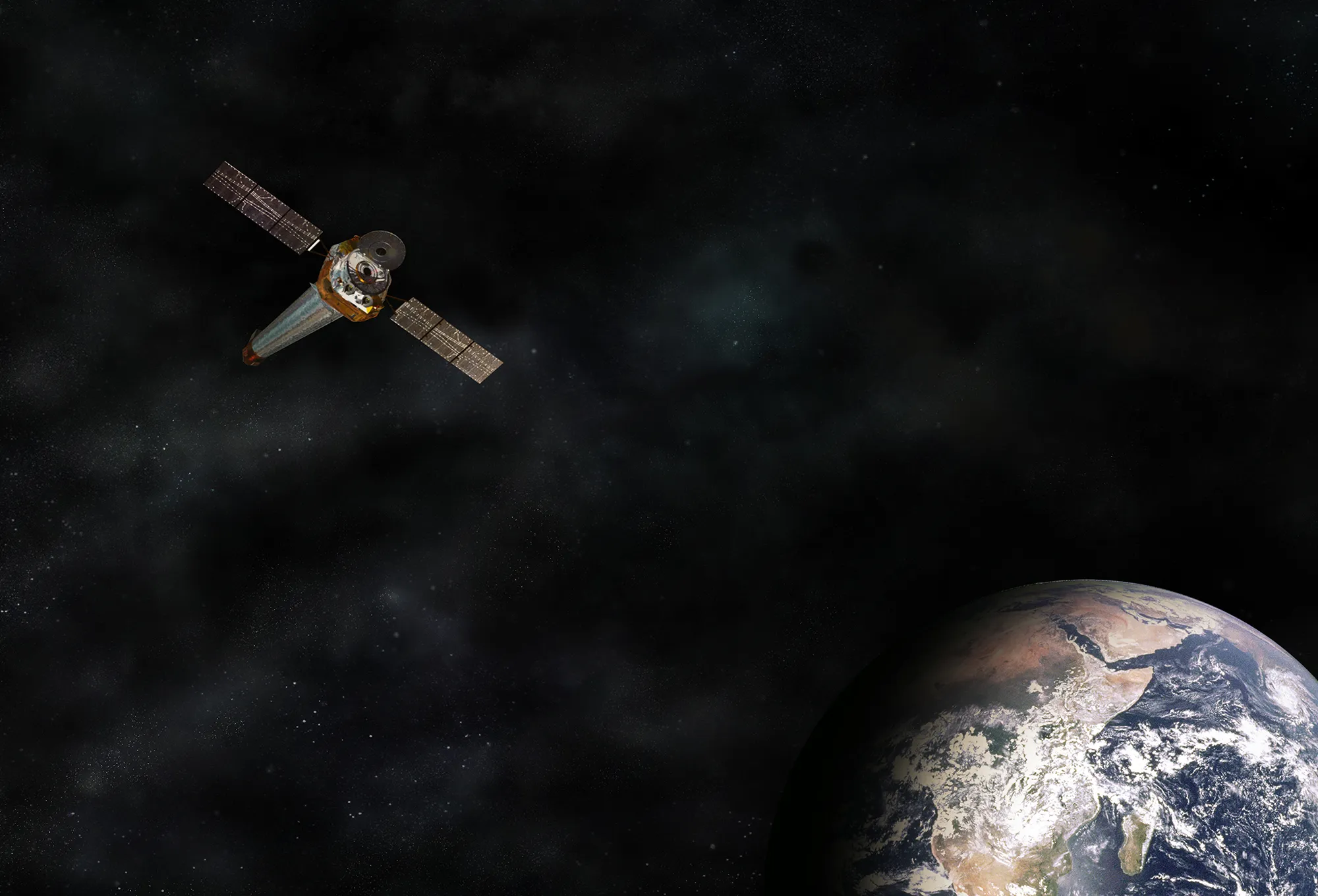

McDowell, who announced his retirement earlier this year, has been a key scientist on NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, often described as the “X-ray cousin” of the Hubble Space Telescope. Launched in 1999, Chandra observes some of the hottest and most energetic regions of the universe, helping scientists study supernova remnants, galaxy clusters, and black holes in extraordinary detail.

Chandra operates in an environment that is becoming increasingly hazardous: low Earth orbit. Here, more than 25,000 pieces of tracked orbital debris—commonly known as space junk—race around the planet at 17,000 miles per hour. This “junk” includes everything from dead satellites to spent rocket stages and fragments leftover from past collisions. Some of the most troubling debris comes from anti-satellite weapon tests in which governments have intentionally destroyed satellites, creating clouds of high-speed shrapnel.

At such velocities, even a paint chip can cause significant damage. McDowell recalls the worst collision to date: a 2009 crash between an active U.S. Iridium satellite and a defunct Soviet-era satellite. The force of the impact was equivalent to 50,000 times the energy of a high-speed car crash. “It pulverized the satellites,” McDowell says. “The debris clouds just passed through each other and kept on going.”

Today, many active satellites are equipped with propulsion systems for “dodge maneuvers,” or adjustments made to avoid potential collisions. This is a huge step in the right direction, according to McDowell. “Twenty years ago, satellites didn’t even have engines,” he says; now, dodging debris is becoming routine.

The challenge lies not just in tracking debris but in predicting near-misses and acting in time. The U.S. Space Force currently monitors orbital traffic, issuing advisories to satellite operators when two objects might come dangerously close. But there’s a catch: the extent of the Space Force’s ability to enforce any corrective action is low.

“They just send an email,” McDowell says. “There’s no centralized authority like air traffic control to tell anyone what to do.”

McDowell maintains his own catalog of space junk, which is published continuously based on public satellite data and made free online via his personal blog.

The Rules of Space and the Governments Writing Them

The legal foundation for space activity is the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, a Cold War-era document which McDowell says was designed for a world with only two spacefaring nations. It stipulates that no country can claim ownership of outer space, and that governments are responsible for activities carried out by their nationals, including private companies.

As McDowell explains, the treaty falls short in addressing today’s crowded and commercialized orbital environment. There’s no current international agreement on the “right of way” in space, no limits on how many satellites can occupy a given orbit, and no clear authority on space traffic control. “You can’t just go clean up old Soviet junk without Russia’s permission,” McDowell says.

Under the treaty, even dead satellites remain the property of the original launching nation. So, although outer space is officially non-sovereign territory, the realpolitik of space access and activity increasingly mirrors that of Earth. McDowell warns that even theoretical clauses in international law are starting to run up against the rapid pace of commercial and governmental ventures in space, as companies like SpaceX, Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic, and beyond begin to press past the atmosphere.

“We’ve had 60 or 70 years of spaceflight,” McDowell says. “Now, the legal and practical implications are starting to hit us in the face.”

If humanity is to sustainably explore and benefit from outer space, McDowell says, we must address the mounting orbital traffic jam. That means new policies, new technologies, and a shared understanding that the space above us is a global common; one that, if neglected, could become unusable for generations. As McDowell puts it: “We need a highway code for outer space. And we need it fast.”