When the pandemic hit six years ago and the world abruptly shut down, Ava Jinying Salzman ’23 found herself jolted back to an old obsession: monsters. As a child, she’d been fascinated with scary things; her earliest drawings were full of skeletons and sharks. In elementary school, she gave her mom a sketch called “Fang City,” in which the buildings, creatures, and landscape were all made out of teeth. She remembers trick-or-treating as a three-headed werewolf—a costume she invented herself, stuffing masks with newspaper and pinning them to her shoulders—while her sister was dressed as a candy corn princess. “I was always curious about why monsters feel so unsettling,” says Salzman, now a graphic novelist, writer, and multidisciplinary artist. “For me, that feeling was exciting more than repulsive.”

Even as she grew older and pursued other interests, monsters still hummed in the background. Then came COVID-19. Amid the chaos, fear, and isolation, the virus exposed deep fissures in American society—and personal fissures, too. Salzman, who struggles with anxiety and ADHD, felt her mental health deteriorate and saw the same happen to friends and family members. A descendant of Chinese immigrants, she watched in horror as anti-Asian hatred and violence surged across the country. A famous quotation from the Italian philosopher and politician Antonio Gramsci started echoing in her ears: “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

Salzman was a first-year College student at the time. After Harvard closed its campus and sent everyone home in March 2020, she spent the rest of the semester and her entire sophomore year in “Zoom school,” as she calls it, logging into class from her parents’ house in Los Angeles and, later, from an apartment in Brighton, Massachusetts. It was an awful, stressful year, she says, but two of those remote courses turned out to be pivotal: one on the “folklore of emergency” and another on the social and cultural history of Japan as told through its monsters. A central theme in both was that during times of upheaval, when normalcy ceases to exist, stories about monsters proliferate. “And so, unexpectedly,” Salzman says, “a pathway opened up.”

She started drawing monsters every day: demons, skeletons, ghosts, beasts, and monstrous creatures of all kinds. Back on campus the following fall, she filled sketchbooks, canvases, and schoolwork with her creations, including one class project in which she made a series of paintings exploring “decomposition as rebirth” and placed them in public spots around Harvard Square. She posted videos on social media of herself slipping exquisitely rendered monster drawings into books at the Harvard Coop for unsuspecting customers to find. Salzman’s senior thesis, for her folklore and mythology concentration, was a graphic novel tracing the journey of her Chinese American family, who have lived in California since the 1860s. Adapted from stories her grandmother told, the graphic novel unfolds as a series of ghost tales incorporating Chinese lore and magical realism.

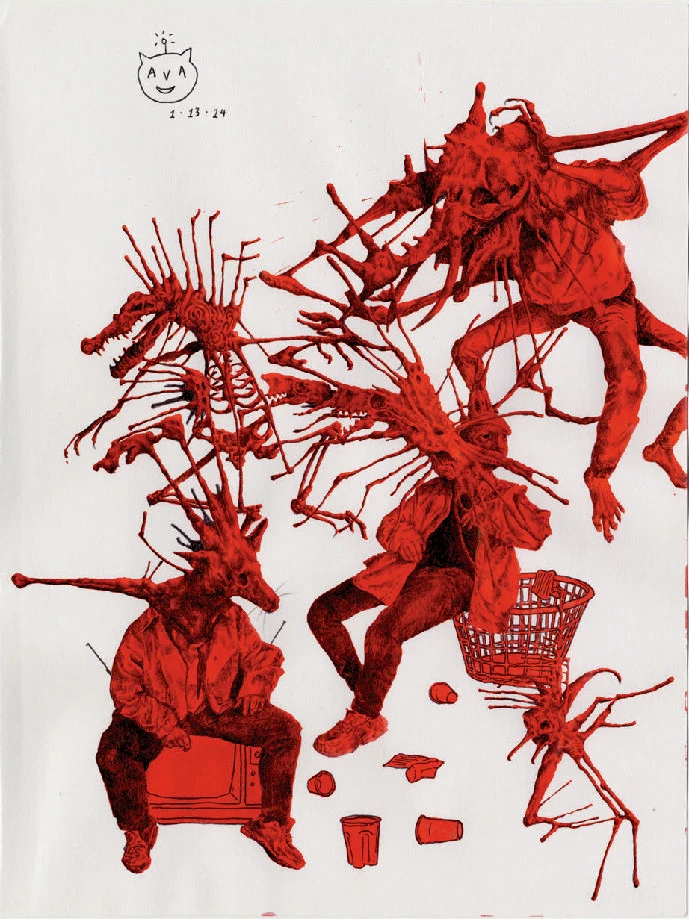

Salzman also embarked on a longer-term project she calls her “Monster Portraits” series. She asked friends and classmates, “What monsters do you carry?” Then, she transformed their descriptions of mental health struggles, haunted memories, trauma, worries, and sorrows into pen-and-ink illustrations. Both ghastly and gorgeous, the images are done in a red so deep and lurid that sometimes the page seems almost to be breathing. “Monsters have always been a way for people to create a form to capture something that is terrifying because it’s abstract or uncategorizable,” Salzman says. “Even if you can’t solve the problem, there’s catharsis in turning something that was uncapturable into a thing you can see and confront and say, ‘This is the beast I’m dealing with.’”

In late 2023, a few months after graduating, Salzman opened a TikTok account and began posting short videos of herself creating monster portraits, using a technique that originated from an accidental ink spill. In the videos, she squirts a few drops of red ink onto the page and gently blows on the liquid until it begins to form some semblance of a shape. Then she uses a paintbrush to extend and refine the monster’s structure, before filling in all the details with a ballpoint pen. “People are often really surprised by the ballpoint pen,” she says, but it’s actually a very precise instrument. Unlike expensive drafting pens that produce a consistent line no matter how hard you press down, ballpoint pens are pressure-sensitive. “You can get so much variability,” she says, “and create this softness and really, really fine detail.”

Almost immediately, Salzman went viral with a video of a creature meant to depict her own anxiety. “I draw monsters to help myself process hard feelings,” reads an introductory caption on the screen, as Salzman holds up her black sketchbook and smiles. At the end of the minute-long video, the piece she produces looks like a creature in flight, or perhaps falling to its knees—half-girl, half-beast, ribcage exposed, heart bursting, a human face screaming into the wind.

When Salzman invited strangers on social media to describe the monsters they carried, people responded with an outpouring of stories. She spent months listening to people’s experiences and producing dozens of portraits to represent a wide range of mental health conditions, as well as afflictions like generational trauma, historical violence, loss, grief, and self-doubt. The monsters are genuinely frightful—sinewy, skeletal, tangled, and broken—but also, at times, surprisingly soulful. In her depiction of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), you can’t help but feel anguish for the terrified children trapped inside the monster, but the monster’s dinosaur grin looks worried, too. In another image, a creature representing unaddressed pain clings to the person it’s tormenting, its face sad and stricken.

The response to her artwork has been “overwhelming, in a good way,” Salzman says. Her TikToks routinely attract 10,000 or more views, and millions of people watched her videos about creating monsters for CPTSD and borderline personality disorder (BPD). Stretching into the thousands, the comments are often emotional. “Thank you for giving me a moment to feel seen and heard,” one reads. Another says: “Never cried at a drawing before.” A few people have requested her permission to get tattoos of her monsters. Salzman always says yes. “One guy was planning to get a version of the BPD drawing all across his neck and shoulders, and I’m really curious to see how it turned out,” she says. “I mean, the whole point of this artwork was to give people a sense of catharsis and peace”—in other words, to let them see their monsters.