In 2003, a young Swiss researcher named Martin Surbeck found himself lost and wandering through a jungle in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Just weeks earlier, he’d responded to an ad for a field assistant position that promised the opportunity to get close to bonobos, an elusive species of primate. As he trudged along in the sweltering heat, slogging through chest-high rivers and dodging the spikes and spines of dense foliage, he started to question his choice. “I thought, ‘What the heck am I doing here?’” he recalls. “‘Nobody knows where I am. What went wrong in my life to have me end up here?’”

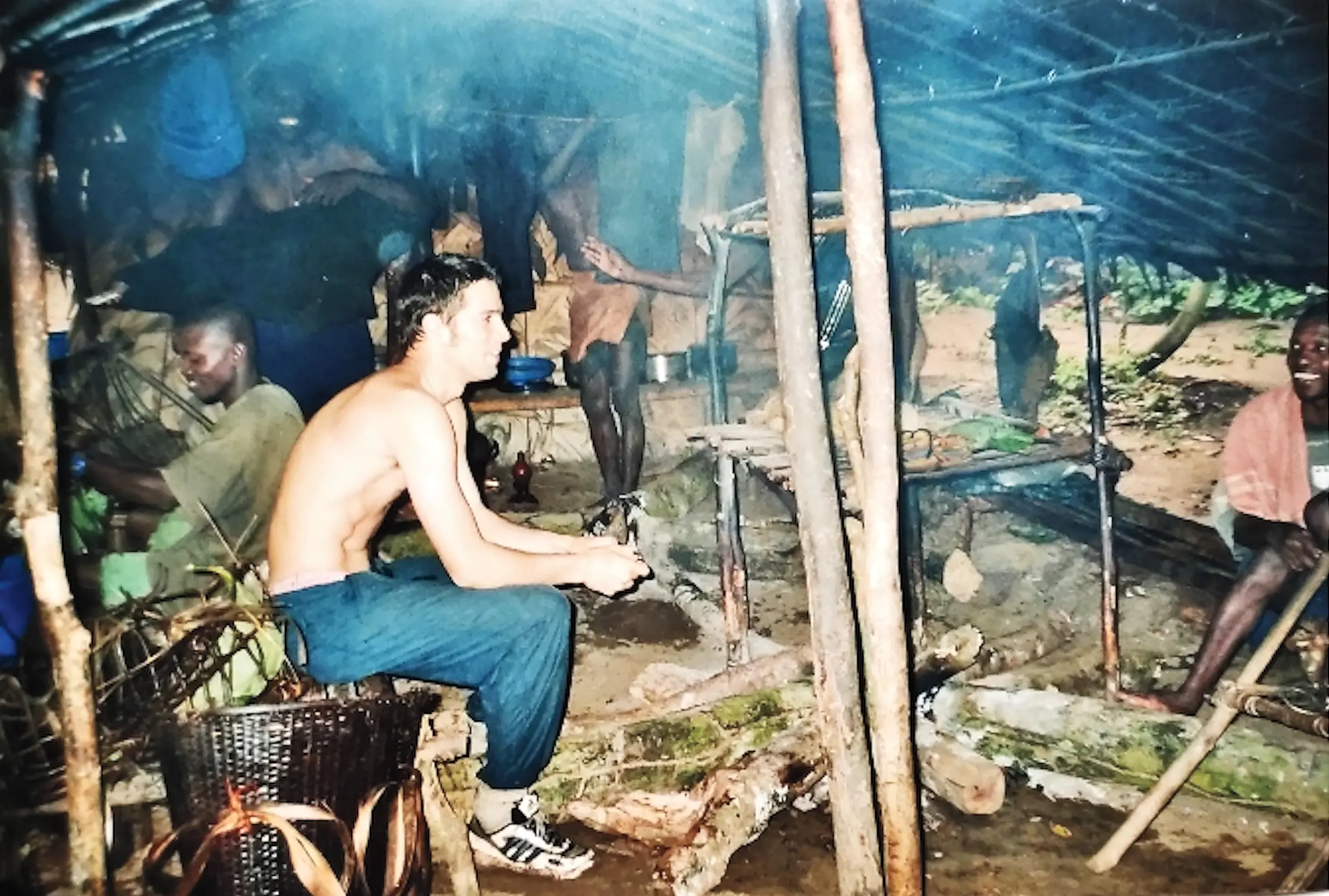

trip into the DRC jungle to follow bonobos in the wild | PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF Martin Surbeck

But he continued trekking, shadowing bonobos as they traversed the canopy above him on a route scientists had not seen them take before. Eventually, a pond packed with water lilies appeared. Surbeck watched as the bonobos waded into the water and plucked out the floating plants like partygoers pilfering hors d’oeuvres from a waiter’s tray. “It was extremely beautiful,” he says. From that moment, he was hooked.

Now an associate professor in Harvard’s department of human evolutionary biology, Surbeck has spent more time studying bonobos in the wild than nearly anyone else. On his jungle treks, he has observed behavior that shatters myths about these supposedly peaceable primates—and sheds light on the strong females who dominate their groups, helping their sons connect with good mates and banding together to keep the males in line.

Scientists have long been interested in bonobos, a highly intelligent, socially sophisticated species that, along with chimpanzees, are our closest living relatives. Found only in the jungles of the DRC, they are the smallest living great apes, standing between three and four feet tall when upright and weighing upwards of 86 pounds. They form social groups ranging from eight to 25 adults and engage in complex forms of communication, including the use of symbols, gestures, and vocalizations.

Due to habitat loss and poaching, as well as their smaller population size, bonobos are an endangered species: only between 10,000 and 50,000 of them remain in the wild. Because most studies have focused on groups in captivity, Surbeck’s long-term fieldwork in the DRC stands out for its ability to follow their communities over time. “Bonobos, like us, are a long-lived species, and until recently we had access only to short snippets of individuals’ lives,” he says. “The emergence of long-term data is very exciting, as it allows us to see how individuals change over time…and to modify the picture we have.”

For one, bonobos have sometimes been considered the hippies of the ape world because, unlike chimpanzees, they don’t engage in warfare and don’t tend to intentionally kill one another. But within a few years of fieldwork, Surbeck saw a variety of interactions that put that idea to the test: females teaming up to kill smaller primates, males constantly bickering among themselves, and bullying among members of a group.

In his latest key study, published last year in the journal Communications Biology, Surbeck and his colleagues used decades’ worth of behavioral observations to show that females reign supreme in bonobo communities—often by forming what can be violent coalitions against males. If a male is causing problems, for example, females will join forces to attack or intimidate him. Males who back down lose social status, while their female adversaries gain it. Males who fight back risk injury and, in rare cases, death. “We have one visual where a male’s face has been ripped off,” Surbeck says. “So, this behavior can have very severe consequences.”

Surbeck and his colleagues have also discovered that the higher a female’s social rank, the better access they have to food—and to quality mates for their sons. In other words, for the male offspring of powerful mothers, it’s not their good looks or high earning potential that attracts females. It’s their mother’s status within the community.

“Females are very central in the group and the males are in the shadows of their moms,” Surbeck notes. “It’s not necessarily because the moms do something special, but because the sons have a key player…to whom they can always go. It’s like a social passport into the interesting domains of the bonobo society.”

Bonobo mothers are not above trying to meddle in their sons’ love lives. During one incident, Surbeck witnessed an outraged mother yank the foot of a low-ranking male trying to mate with an attractive female—in an effort to keep them apart—because she wanted her own son to be with that female. Relatedly, because mothers and sons stay together for life, a bonobo mother can help boost her son’s chances of producing a higher number of grandchildren.

“This pattern helps illustrate one possible pathway for the evolution of menopause,” Surbeck explains. “It can be advantageous for older females to shift from having more children themselves to supporting existing offspring and grandchildren, thereby improving the survival and reproductive success of their descendants.”

To gather data, Surbeck and his teams have spent countless hours over the years following bonobos, earning their trust, and documenting their behavior while based at two field sites: first at LuiKotale (in the DRC’s Salonga National Park, Africa’s largest tropical rainforest reserve) and later at Kokolopori, a community preserve. Days in the field begin at 3 a.m. with a hike through the jungle to areas where bonobo communities slumber in their elaborate treetop nests. Researchers then follow a group until sunset, trekking through the jungle’s labyrinthine underbrush as unobtrusively as possible, while the bonobos amble along or stop at feeding or grooming sites.

Female bonobos reign supreme, often by forming violent coalitions against the males.

For Surbeck, 49, the lush and perilous jungle fieldwork is exhilarating. He spent the majority of his late 20s and early 30s in the field, sometimes for as long as nine months at a time, tracking wild animals from dawn to nightfall, an intense practice known as focal following. “Colleagues will say, ‘I’m so glad I don’t have to do any more focal follows,’” he says, “and I’m just like, ‘Hell, if only I could do more focal follows.’”

Surbeck was born in a small town in Switzerland, where he spent his summers in the Alps helping out with the cows on local farms. He quickly realized he wanted to work with animals. He earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology and zoology from the University of Zurich, spending time in India and Africa, where he studied birds and wasps. His early fieldwork with bonobos led to a doctoral degree at the University of Leipzig, where he focused on dominance, competition, and cooperation among bonobos, which other scientists at the time knew little about.

In 2016, Surbeck established a new DRC field site at the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve, in collaboration with the Bonobo Conservation Initiative and Vie Sauvage, conservation organizations that had formed the reserve in 2003. In 2019, Surbeck joined the Harvard faculty; his research team spends time at Kokolopori. The site enables him to study a population of bonobos—three distinct communities that roam in that region—and compare those groups’ behaviors to those he documented while at LuiKotale.

The individuals in the three Kokolopori bonobo groups are identified by the names of colors, musicians, and bodies of water (mostly in French). Researchers know them intimately. Much like humans, Surbeck says, bonobos have unique personalities and complex behaviors that make them difficult to stereotype. In both Kokolopori and LuiKotale, he’s been struck by the dramatic, soap opera-like aspects of bonobo society.

He points to a young female named Amu in LuiKotale who had a hard time settling into a community. “She drove everyone a bit crazy: the males in the group, the females who were loosely attached to those males,” he says. “Yet the males would travel far beyond their usual home ranges to search for her whenever she left the group, trying to persuade her to return. When she did come back, she immediately became the center of attention. I have never seen anyone as popular as Amu.”

In Kokolopori in 2019, Surbeck witnessed a trio of females gang up on a troublemaking male whom researchers had identified as Gris. He had entered “a feeding tree and was kind of pestering” others and then, “all of a sudden, three or four high-ranking females just darted down on him, out of the blue,” Surbeck recalls. “He leapt out of the tree, barely making it out, and ran off.” The females chased him away into the jungle and returned to the feeding tree a few minutes later “as if nothing had happened.”

He expected Gris to reappear as well, with a few scratches and a bruised ego. But he didn’t show up again on a research camera until more than a month later, roaming alone. “He eventually re-associated with the group,” Surbeck says. But he had clearly been put in his place.

Surbeck’s research has documented many such instances of female dominance. His Communications Biology study used observational data gathered between 1993 and 2021 to reveal that of 1,786 conflicts documented between single males and single females, females won the majority of them.

One primary source of that female power is cooperation. Females can prevail alone, Surbeck says, but their rate of success is much higher when they band together with other females or know they have that back-up support if needed. In communities where “they form frequent female coalitions,” he says, “they always win.” Intimidating behavior, such as chasing and screaming, usually does the trick. But female coalitions, as noted above, are not opposed to a little violence; a male could lose a finger or a toe for crossing the wrong female.

In an earlier study, published in 2019 in Hormones and Behavior, Surbeck and colleagues pointed to a few potential sources of female cooperative bonding: same-sex sexual behavior and oxytocin. Female bonobos can often be seen rubbing their genitals together in conjunction with situations of high tension or when a conflict is brewing. The researchers discovered that the females had higher levels of oxytocin—which can engender good will and cooperative behavior—following these same-sex sexual activities.

Bonobo females aren’t monogamous, and they engage in frequent sexual activity—to release tension, to promote cooperation and social cohesion, as well as to procreate—with multiple partners, both of the same and opposite sexes. For most social mammals, males leave their natal group (and join a different one) when they reach sexual maturity. But in bonobo society, young females are the ones to leave, moving to groups featuring other females to whom they are not related.

Male bonobos, Surbeck has found, have their own ways of resolving conflicts with each other. In 2024, he and his colleagues published the results of a multi-year study showing that males in Kokolopori exhibited higher rates of conflict with each other than did their chimpanzee counterparts. Yet while they bickered more than chimps, their squabbles rarely resulted in physical harm. At the end of the day, the “peace” that male bonobos keep, Surbeck says, is “rooted in permanent argument”—not extreme violence.

Surbeck is currently focusing on exploring this less violent, more socially interventionistic approach to disputes—along with cooperative behavior among individual bonobos of the same and different communities. Unlike chimpanzees, bonobos can get along with those outside of their own social groups. Some even move among communities, switching in and out, over time, without major fights and violence.

The “peace” that male bonobos keep, Surbeck says, “is rooted in permanent argument.”

Contrasting behaviors of different primate species, Surbeck says, can help us evaluate how humans think about our own societies—and identify alternative ways of relating. Some people may look at human warfare, hostility, male sexual violence, and strictly patriarchal social structures and believe those behaviors to be a part of our DNA, he explains, but bonobo communities show that these aspects of society are not evolutionarily inevitable.

Humans are part of “this group of animals with extremely flexible behavior and a strong capacity for social learning. Our patterns of conflict, cooperation, gender relations, and power are therefore not rigidly fixed by biology,” he points out. “Instead, they can change depending on history, culture, and environment, which means there is a wide range of possible ways for human societies to be organized.”

Cooperation, he says, is a vital avenue of his research moving forward. “What brings the group together in a way that they can stay with each other?” Surbeck wants to know. “Under which social and ecological conditions, and given which individual characteristics, is cooperation and exchange between groups most likely to occur and be maintained?”

Surbeck returned to Kokolopori for nearly two months this winter, meeting with staff and researchers, checking in on schools and hospitals connected to the project, and meeting with local and national officials to address ongoing problems of deforestation and hunting. What he fears most is that bonobos might not survive this century. “We could lose one of our closest living relatives not because we were unable to save them and their environment,” he says, “but because we did not care enough.”

He also spent some time among the bonobos in the forest. One of his greatest joys, he says, is “walking with the bonobos through their environment—when the vegetation is not too thick and we can stroll together—and simply sharing their presence, quietly witnessing the lives of a different species.”