Few images in modern sports are more familiar than the back of New England Patriots No. 12: Tom Brady’s navy blue jersey, his silver and red helmet, his strands of close-cropped brown hair. But seeing them in needlepoint—woven in tiny, exquisite detail by Harvard hockey legend Joe Bertagna ’73—is like seeing them for the first time.

No detail has escaped Bertagna’s notice or the work of his extra-large goalie hands. The tight brown stitches representing the fringe on Brady’s neck are gridded unevenly; there’s a small green sticker between the 1 and 2 on his helmet. On his jersey, the “Y” in “BRADY” is a weird shape, for a “Y.”

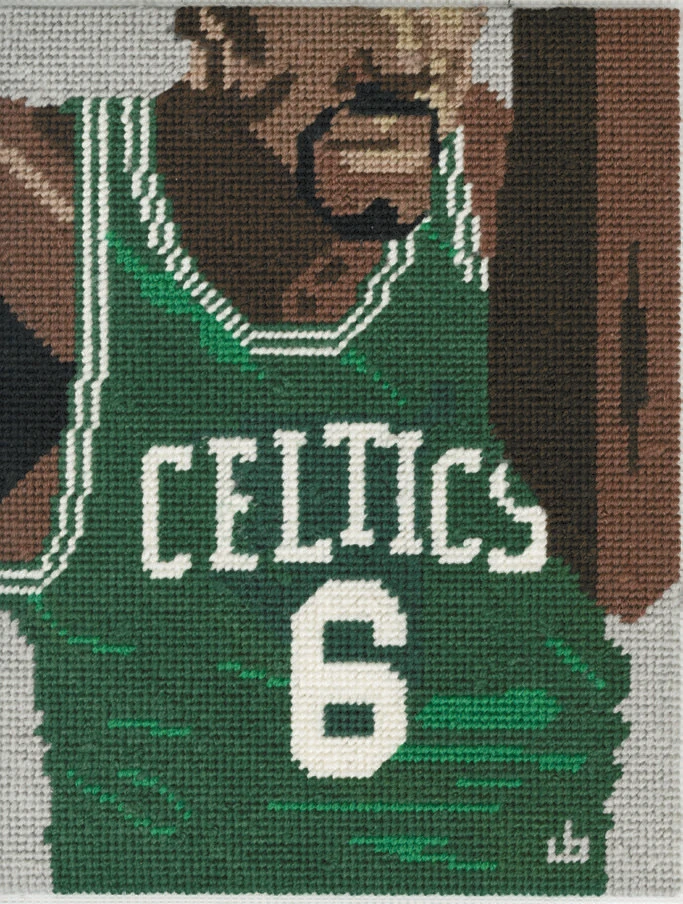

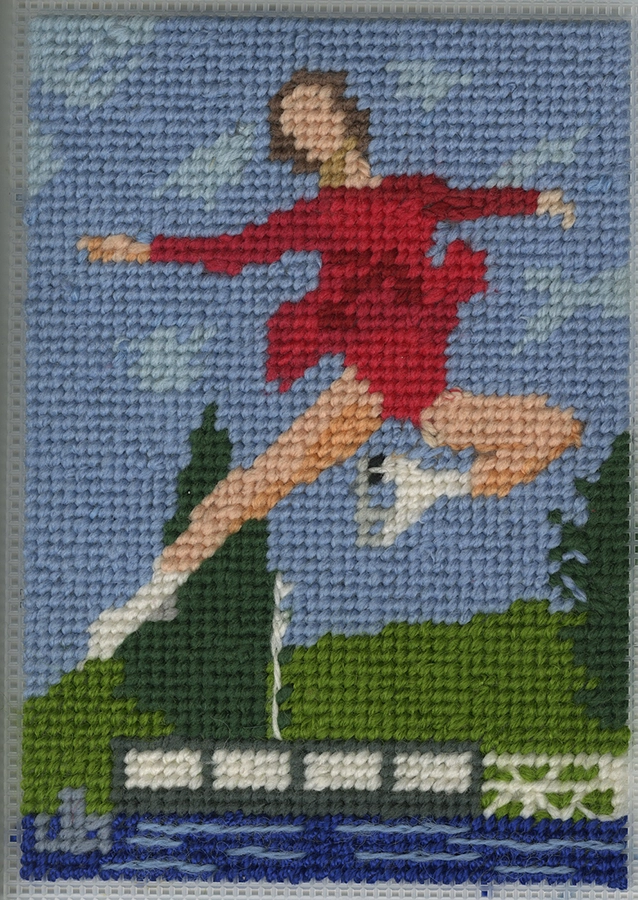

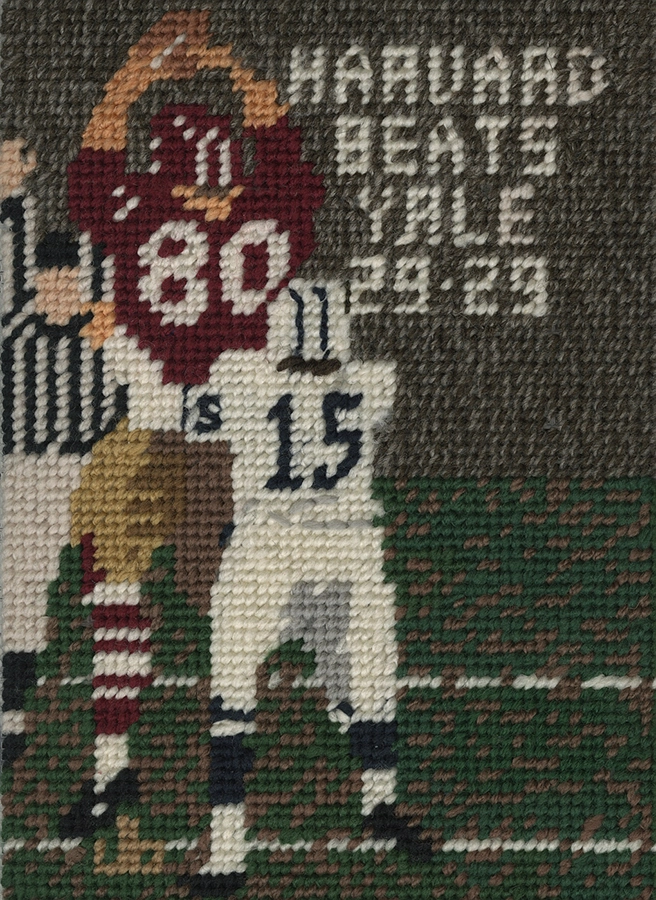

Bertagna enjoyed needlepoint as an evening hobby throughout much of his post-collegiate career as a hockey coach and commissioner. When he retired a few years ago, he embarked on a new ambitious project: recreating the most indelible figures in Boston sports history in brightly colored thread. He’s sewn Celtics great Bill Russell in his prime; Bruins defenseman Bobby Orr’s “flying goal” to clinch the 1970 Stanley Cup; Olympic figure skating gold medalist Tenley Albright ’57, M.D. ’61; Patriots kicker Adam Vinatieri’s field goal in the snow.

“I’ve done needlepoint for 30 or 40 years, usually as a mechanism to relax,” says Bertagna, whose creations were on display in the Sports Museum at Boston’s TD Garden last year. “And I love these types of projects. I like a beginning, middle, and end.”

Sports, replete with bright colors and recognizable silhouettes, turn out to be a perfect fit for this particular craft. Viewed close up, Bertagna’s projects are lively with detail. Slight color variations evoke the shadows of small folds in Russell’s green Celtics jersey; Albright’s crimson skirt flutters mid-air.

“It’s just amazing,” says Stan Grossfeld, a Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe photographer. “Joe’s an artist, and he’s got the nuances that a great artist would have. He can see light. He’s meticulous [with] detail, and he has the patience.”

This past December, Bertagna auctioned off 30 of his sports needlepoints at Prince Pizzeria in Saugus, a suburb north of Boston, to raise money for the Sports Museum’s anti-bullying programs. Taken together, the items up for grabs involved “hundreds of thousands” of stitches, Grossfeld notes. The largest work in the collection, an 11-by-17-inch recreation of Grossfeld’s 2013 photo of a Boston policeman celebrating a grand slam by Red Sox star David Ortiz, is made up of nearly 19,000.

“I’ve always had an artistic bent,” Bertagna said a few days before the auction. Needlepoint, he said, “has served me on a bunch of different levels, and I’m proud of how this project came out.”

Since his college days, Bertagna has routinely popped up in unexpected corners of New England’s social and cultural scene. As Harvard’s goalie, he appears for about 15 seconds during the hockey game in the 1970 movie Love Story. During his undergraduate years, he was buddies with Benazir Bhutto ’73, the late prime minister of Pakistan. Alongside his hockey administration career, he has published a handful of books, including a 1986 history of Harvard sports; in 1981, seven years before The Onion’s founding, he edited Not the Boston Globe, a single-issue parody newspaper with the front-page headline, “Reagan still asleep.”

Bertagna, whose mother practiced cross-stitch, picked up needlepoint as a way to unwind from the pressures of his sports-related day jobs, which have included six seasons as the Bruins goalie coach, an Olympic Games on Team USA’s coaching staff, 23 years as commissioner of the Hockey East conference, and the distinction of serving as the first head coach for Harvard women’s hockey in the late 1970s. Early creations included a Chicago Blackhawks logo for his brother and a crimson rocking chair cushion with a Harvard “H” on it for his mother.

“I needed something mindless at the end of the day, where I didn’t have to think about the things that were stressing me out,” Bertagna says. “I would do these fun little projects and give them away as gifts.”

The Sports Museum project came about with encouragement from Grossfeld, who became friends with Bertagna around 2021 when they both attended a weekly gathering of local sportswriters. Boston Globe columnists Dan Shaughnessy and Bob Ryan and broadcaster Lesley Visser—the first female National Football League analyst to cover a game on TV—have received needlepoint gifts from Bertagna over the years. “I told him he should do this as a project, because these were unlike any needlepoints I’d seen before,” Grossfeld says. “You don’t associate needlepoints with sports. It’s butterflies and flowers.”

Bertagna began the project in earnest as his hockey administration career wound down: his tenure as the commissioner of Hockey East ended in 2020, and his executive directorship of the American Hockey Coaches Association came to a close in 2024. With extra time on his hands, Bertagna sewed for three or four hours each morning and evening at his home in Gloucester, Mass. At that pace, smaller four-by-six-inch pieces take him about a week; the Ortiz home run celebration took five months. He gets his materials at Coveted Yarn, a neighborhood shop in a church basement. According to a story Bertagna likes to tell, he has never seen another man in the store, but he once happened upon a group of elderly women knitters arguing about Patriots offensive coordinator Josh McDaniels.

Completing the Sports Museum project has pushed Bertagna beyond his needlepoint comfort zone, prompting him to delve into different sports and more intricate designs. “I’ve spent my whole life in hockey, so I have a better familiarity with it,” he says. “When you’re looking at something, a picture’s a picture, but if you understand how [jersey fabric] folds and equipment feels, you can have a better grasp.”

The sports represented in his latest project run the gamut from soccer to marathon races to golf. The result is an unlikely history of New England sports that is both comprehensive and deeply personal, including a portrait of the artist in his Arlington High School jersey and hockey mask, as well as a scene of his wife, Kathy, playing golf with a hockey stick (she thought her legs looked too big and told him to redo them).

For a few needlepoint works, he experimented with black-and-white color palettes, which require unsparing precision because of the lack of color cues. For others, he had to sew faces, which he doesn’t enjoy. “Faces are hard,” he explains. “They come out cartoonish.”

Though proud of the project, which he is thinking about making into a coffee table book, Bertagna was ready, as the auction neared, to get back to the less ambitious, personal gift items he can fiddle with at the breakfast nook or while watching TV.

But first, there was money to raise. On the night of the fundraiser, the back dining room at Prince Pizzeria buzzed with a boisterous crowd eating pasta and pizza while browsing the culmination of Bertagna’s yearslong effort. “How’s your back?” one man greeted another over the noise.

“It sucks!” the second crowed, grinning.

Clad in a gray tweed jacket and a Red Sox tie, Bertagna moved through a throng of supporters that included family, childhood friends, his Boston sports media pals, and several teammates from his Harvard hockey days.

“He sat back knitting while we did all the work!” joked Kevin Hampe ’73, who played defense while Bertagna tended goal. Hampe didn’t know about his friend’s needlepoint hobby until it was featured in Grossfeld’s January 2025 photo essay in The Boston Globe. There wasn’t a needle or thread in sight when the two were roommates in Eliot House—one imagines that if there had been, Bertagna never would have heard the end of it.

There were rounds of live bidding for six of Bertagna’s creations, with a silent auction for everything else. Boston radio personality Hank Morse played auctioneer, needling the crowd into larger and larger bids and roasting various surrounding towns. Three works bundled together, including the Bill Russell needlepoint, netted $1,000—the highest bid of the night. The rest—33 in all—went for several hundred dollars apiece.

Overall, Bertagna’s work raised $11,226 for the museum, “about twice what I expected,” he later said. But the biggest get, arguably, was the commissioning of a custom creation from the artist himself, which sold for $900.

“No faces,” Bertagna warned the winner.