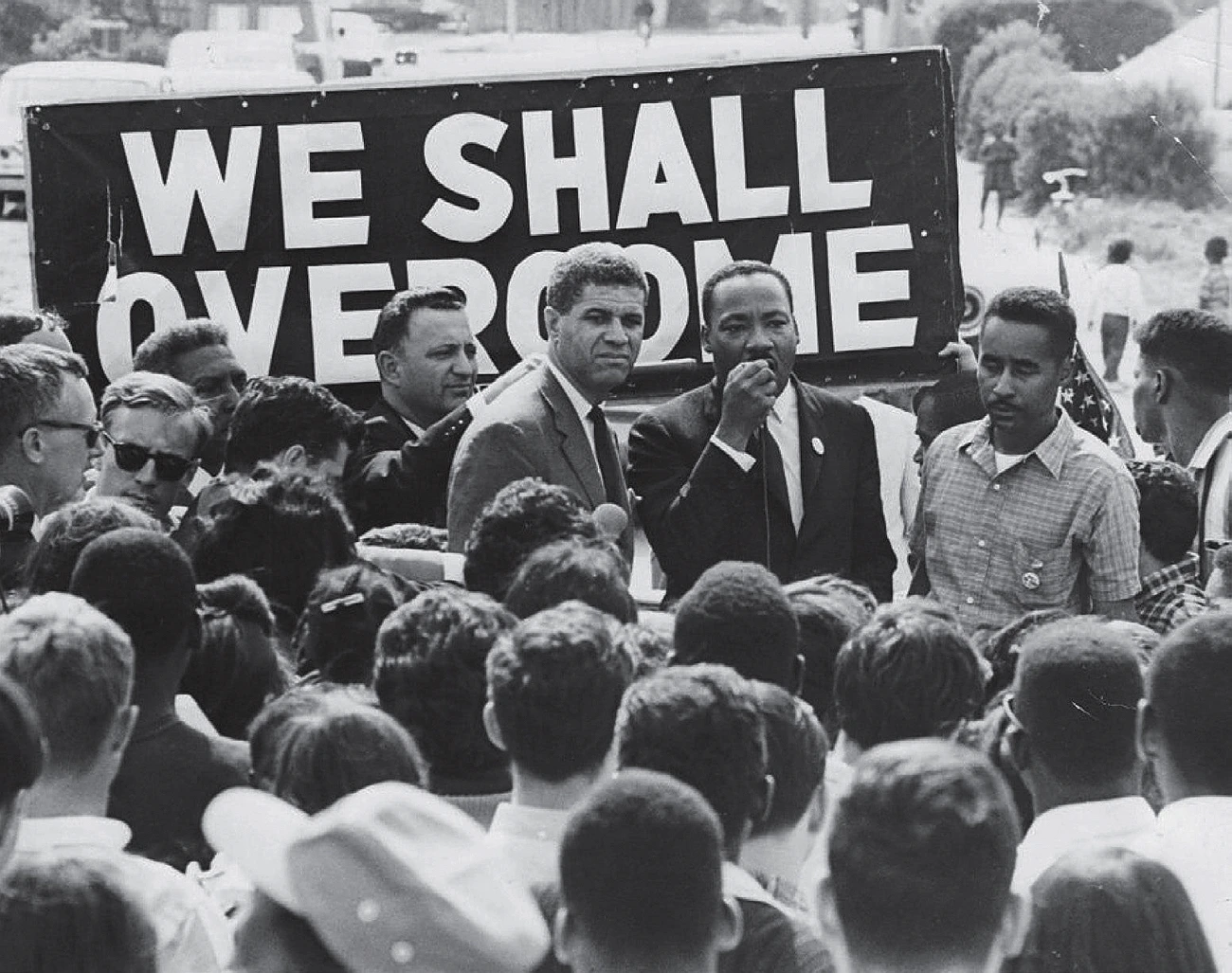

“Part of the problem with mythology,” said political philosopher Brandon Terry, sitting in a near-empty Allston diner on a sweltering afternoon in late June, “is that it doesn’t really prepare you for the fight you have to have. It doesn’t prepare you for how long it is, how arduous it is, the kinds of disappointments you’ll face.” A scholar of the civil rights movement, Terry was talking about events more than half a century in the past: the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech; Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama, and the marchers’ defiant return to the Edmund Pettus Bridge; Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on the Montgomery bus; Brown v. Board of Education; and all the other familiar, celebrated touchstones that make up what he calls the “romantic narrative” of that era.

But he was also talking about right now. The retrenchment and backlash against “wokeness” and anything that can be labeled “DEI.” The rollback by the Trump administration of federal antidiscrimination policies in place since the civil rights movement. Book bans targeting “diversity” and state laws restricting the teaching of Black history. Cuts to medical research benefiting Black patients. Lately, the “fight you have to have,” Terry believes, has been escalating dramatically. In a talk last spring at the Princeton Public Library, Terry, a 2005 College graduate and Loeb associate professor of the social sciences in African and African American studies, described 2025 as “a time where it seems like the great victories of one era are being slowly turned into the ruins of our present.”

We are at a disorienting moment in American life. While one part of society reels from what Terry labels the defeat of the Black Lives Matter movement, another asserts—with growing political success—that measures intended to counter racial discrimination are themselves discriminatory. Underlying everything, according to Terry, is the gauzy story we’ve told ourselves about the 1950s and 1960s—and the warping effects that story has on the politics of today. His new book, Shattered Dreams, Infinite Hope: A Tragic Vision of the Civil Rights Movement (Belknap Press, out this October), is an attempt to correct the record, to offer a more truthful and clear-eyed account of what happened, what it means, and how it might point a way forward.

Complaints about the “arc of justice” hagiography are not new. Critics have long warned that depicting the civil rights struggle as a heroic and inevitable triumph glosses over the very real conflicts and complexities that affected the movement, the failures and flaws, the numerous ways its leaders’ actions were shaped by events they didn’t control. That triumphal story also brushes off racial inequalities that persist. “Part of the intensity of cultural explanations for Black disadvantage in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s stems from, I think, the success of the romantic narrative,” Terry says. “Because if everything’s been fixed, if we have in fact overcome—or are just about to overcome—then the rest of this must be your fault.”

But now, amid what many see as an alarming leap backward, the romantic narrative is breaking down. And what threatens to take its place, Terry worries, are pessimism and bitter resignation, the belief that things will never get better. This is a reaction he understands—at times he has shared it—but ultimately, he believes, it’s self-defeating. Instead, he advocates a different response: hope.

The title of Terry’s book comes from a sermon published in 1963, in which Martin Luther King Jr. speaks of “blasted hopes and shattered dreams.” Unfolding across 400 pages, the book is an intricately woven philosophical argument, with a table of contents that namechecks Immanuel Kant, John Rawls, and the Jamaican American philosopher Charles W. Mills. There is a deep analysis of a 1920 essay by W. E. B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. 1895, with a blood-curdling description of the Grand Canyon as a metaphor for Jim Crow. Terry offers a sympathetic, deep-in-the-weeds critique of Afropessimism, the theory that describes anti-Blackness as a permanent condition of civil society, with no possibility of emancipation or equality.

But Shattered Dreams is also an absorbing, emotional narrative, with an idea at its core that lands like a lightning bolt.

The civil rights movement, Terry contends, is a “tragedy”—not in the modern-day colloquial sense, but in the way that Aristotle and the ancient Greeks might have recognized it, as a story of conflict without easy resolution, full of deep moral tensions, unintended consequences, and unforeseen occurrences. A story of “intertwined victories and defeats,” in which nothing is inevitable.

It’s also a bigger story than the one that’s usually told, lasting not just a decade or two, but generations. Terry agrees with the “long civil rights movement” historians, who push back the start date to the early twentieth century, when the Great Migration made clear that Black Americans’ struggle against oppression would need to be national, not just confined to the South. The early 1900s saw the founding of organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and Black labor unions like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This longer history also encompasses the militant activism of Black soldiers, who returned from World War I with sharpened demands for equal citizenship. In this telling, figures like Du Bois were not precursors to the civil rights movement, but part of it.

Du Bois himself pictured the fight against racial injustice as a “long siege,” Terry notes, and King explicitly said in his shattered dreams sermon that he didn’t expect the movement to fully succeed within his lifetime. Thinking in these terms raises existential questions—if profound inequality still persists, was the effort worth it?—but it also allows people to see themselves as part of a continuing struggle in which political failures and individual shortfalls can be steps on the road toward progress. “This goes right to the heart of the matter,” Terry says. “I’m trying to remind people of the genuine human flourishing that’s at stake in making people’s lives even a little bit better.”

“If all you teach is hopelessness...you don’t train people to look for unexpected contingencies.”

All this—the long siege, the partial victories, the chance opportunities—forms the crux of his argument against Afropessimism’s nihilistic despair, which Terry has seen rising over the past year. At the diner in Allston, he talked about how the civil rights era coincided with several seemingly unrelated events—the Cold War, the mechanization of Southern agriculture, the rapid expansion of television. “These things had nothing to do with the problem of Black subjugation as such,” he said, “but they became part of the terrain for overturning it,” converging contingencies that civil rights leaders took advantage of (just as civil rights activists today have used cellphone cameras and social media). “But if all you teach is hopelessness and that nothing can change,” Terry added, “you don’t train people to look for unexpected contingencies.”

From this perspective, failures are not just setbacks; they’re opportunities for insight and revised tactics—which sometimes carry their own moral predicaments. Terry recounts how, during the 1962 desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia, the local police chief outmaneuvered King by arresting protesters without spectacular violence, which dampened media coverage that might otherwise have provoked federal intervention. In Birmingham, Alabama, the following year, Bull Connor, the legendarily brutal commissioner of public safety, at first followed the same playbook.

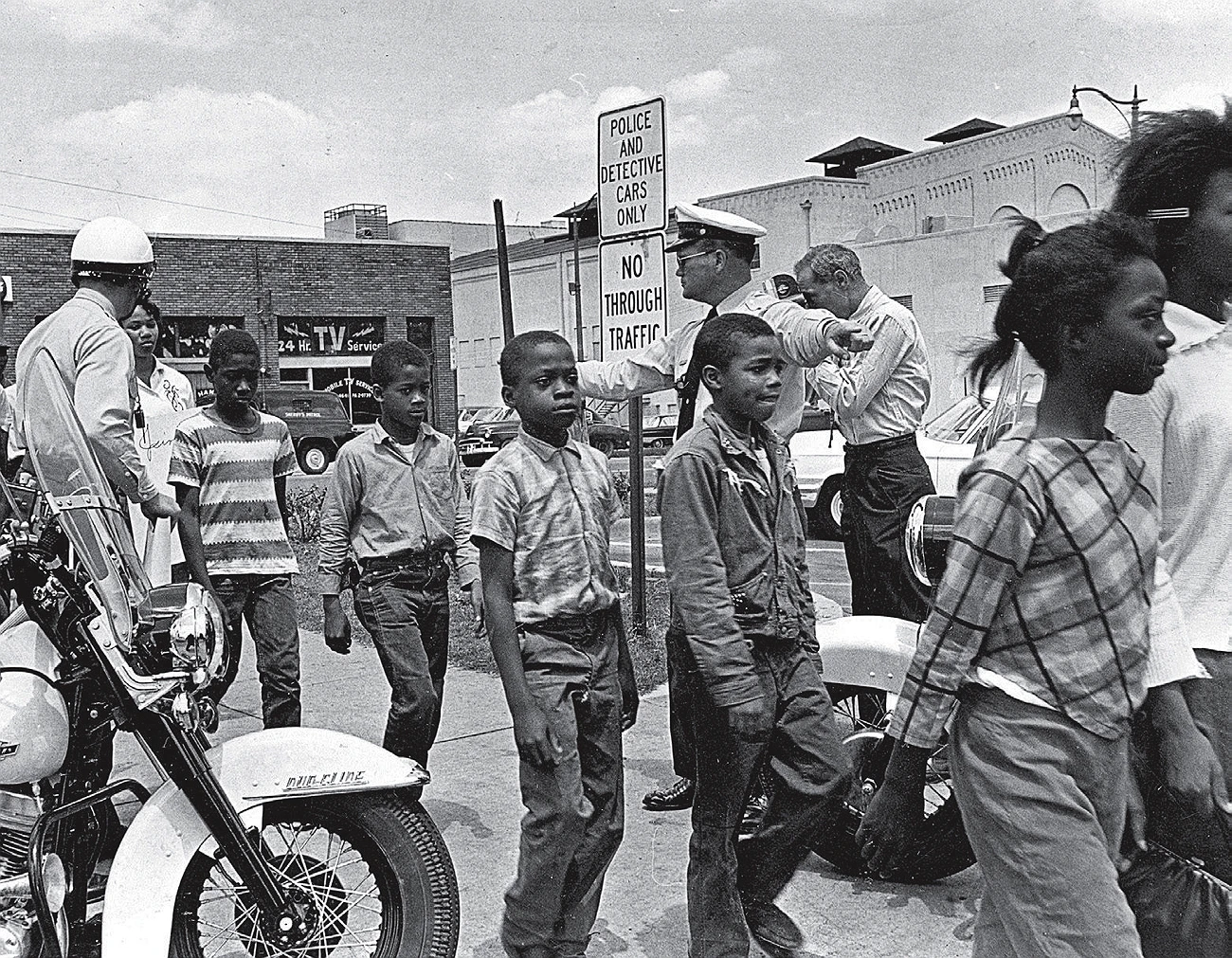

Desperate for national attention, Birmingham organizers decided, with King’s tacit approval, to recruit children as young as elementary-school age to march in what became known as the Children’s Crusade. This was a wrenching dilemma—the organizers knew they were risking children’s lives. King himself had said during an earlier strategy session with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that he did not expect everyone to come back alive from the Birmingham campaign.

This time, Connor reacted as expected, and the photographs and videos that emerged—of children being beaten with clubs, attacked by police dogs, and sprayed with firehoses—sparked international outrage and prompted President John F. Kennedy to support civil rights legislation. Even today, these are among the first images that spring to mind when talking about the civil rights era. Reading Terry’s account, which describes King locked in a motel suite for hours, stricken with doubts about whether to “send in the children,” it’s hard not to feel haunted by how differently it all might have turned out.

At 41, Terry has the kinetic presence of an even younger man, but the voice—patient, weighty, slightly syncopated—of someone years older. Friends and colleagues invariably describe him as a generational thinker. (They’ll also tell you that he has read everything. “I don’t think he sleeps much,” says Harvard philosopher Tommie Shelby, who was Terry’s undergraduate thesis adviser.) Dartmouth political theorist Keidrick Roy, Ph.D. ’22, who came to Harvard to study with Terry, describes their conversations as “jazz sessions,” full of riffs and unexpected harmonies and questions that kept pushing deeper. Philosopher and activist Cornel West ’74, Terry’s mentor and friend for two decades, calls him “the towering humanistic intellectual of his generation,” an heir to Erasmus and the great twentieth-century German philologist Erich Auerbach. “To have a Black man who is part and parcel of that great tradition,” West says, “rooted in the best of the Black intellectual tradition but also so immersed in the grand humanistic tradition of the West, is a magnificent thing.”

Terry began work on Shattered Dreams during his dissertation days at Yale, where he earned a Ph.D. in political science and African American studies in 2012. But the truth is, this book started in Baltimore.

Terry grew up at the edge of the city, in an unincorporated community called Randallstown. It had been a Jewish neighborhood for decades, but by the time he was out of elementary school, it was almost entirely Black. “I had these extraordinary experiences, where, at the same time that I was the only Black kid at a couple of kids’ bar mitzvahs, I also went to visit my brother in federal prison,” says Terry, who was one of five children. His father, a driver for the American Red Cross, had grown up in public housing. His mother, a public-school social studies teacher, was from a Black working-class area in the northwest part of the city, not far from where the Freddie Gray riots started in 2015. There were books all over the family’s house—textbooks, encyclopedias, books left over from her time in college. “And I would just read them constantly,” Terry says.

His uncle offered to pay the Harvard application fee—$65, the same price, Terry recalls, as a pair of Nike Air Force 1 sneakers.

He was about nine the first time he read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. “I didn’t digest all of it,” he says, “but the stridency and his more nationalist formulations—they hit very powerfully for young people, because they just seem to have all the answers. It’s kind of a sealed worldview. And in a place like Baltimore, there’s a lot about Black nationalism that seems to clarify things, especially at that time, when you could see really clearly the stark racial divide, and how class inequalities were mapped onto race inequalities.” Malcolm X connected on a visceral level, too. “His message about the existential cost of oppression, the sense of hopelessness, sense of despair, waywardness—I mean, this was an era of unprecedented homicide rates, devastating levels of drug addiction,” Terry says. “And these were things that we had intimate experience with in our family, things that we saw, things that we knew.”

Politics were intensely debated around the kitchen table. His mother, grandmother, and uncle Eddie, a Vietnam veteran who worked for the Social Security Administration, were center-left liberals who admired King and believed that integration was worth sacrificing for, even in the face of persistent discrimination. His uncle Ronald was a Black nationalist who moved out to rural Maryland and began growing his own food. “He took self-sufficiency really seriously,” Terry says. “He bought bombed-out houses in Baltimore and rehabbed them with his own bare hands and a crew of people he had trained. He was very deeply skeptical that we were ever going to change the broader society’s attitudes toward Black people, absent some amassing of power by Black people themselves, economically, socially, politically.”

As a high school junior, Terry scored high on the PSAT, and Yale sent him a letter, encouraging him to apply. He ripped it up immediately. “I thought it was just absurd,” he says. “No one from my high school had ever gone to an Ivy League school. We barely knew people who went to college, especially outside of the historically Black colleges in Maryland.” Then Harvard sent a letter, which he showed to his uncle Eddie as a joke. But Eddie didn’t laugh. “I’ll never forget, he just kind of looked at me and said, ‘Why is that funny?’” Terry says. “And my fear and discomfort kick in, because I realize he’s pushing.” His uncle offered to pay the application fee—$65, the same price, Terry recalls, as a pair of Nike Air Force 1 sneakers—and promised to give Terry the same amount if he got in.

He did get in, and during his first months on campus, he felt as much like a fish out of water as he’d feared. But he soon found his way to the Black Men’s Forum (today he serves as its faculty adviser) and began writing a column for the Crimson, “On the Real,” where he often explored issues of race.

He declared a concentration in government and African and African American studies. Black nationalism was still on his mind. “I think one reason nationalism is very attractive to striving young people is that they have ambitions that they can see thwarted by their membership in a stigmatized group,” he says. “So, there’s a lot of hostility and a lot of frustration.” But he was also starting to read King and other thinkers whose work complicated his understanding of race. “Something that became unavoidable for me was the way that fictions of Black collective identity paper over all manner of divisions based on sexuality, gender, ethnicity, religion, class.” (That idea resurfaces in Shattered Dreams, as another critique of the romantic civil rights narrative.) His senior year, he wrote a thesis exploring whether there was any version of Black nationalism that could survive those criticisms. In the end, he decided there wasn’t. By then, he says, “King had started to loom much more largely.”

Much of his career since has been spent plumbing the depths of King’s political thought—and working to dispel the romantic caricature that he says has “entombed” the civil rights leader. In 2018, the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination, Terry coedited To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr., along with Tommie Shelby, the Titcomb professor of African and African American studies and of philosophy. “That book was very much Brandon’s brainchild,” Shelby says, intended to refute King’s image as a colorblind dreamer. King wrote five books of political philosophy and held numerous positions—on militarism and war, labor rights, reparations, universal basic income—that even today fall outside of the American mainstream.

“That book was a real corrective,” says former Harvard historian Elizabeth Hinton, now a professor at Yale who codirects the Harvard-housed Institute on Policing, Incarceration, and Public Safety with Terry. “People have frozen King at ‘I have a dream’ and taken lines from that speech—ignoring the totality of the points he was making, never mind grappling with the full corpus of his activism and thought—to argue that King wouldn’t support things like racial justice initiatives or DEI. And the treatment Brandon gives him really shows how much his philosophy has been distorted.”

In 2023, Terry was part of a committee that guided the construction of The Embrace, a 20-foot-tall bronze monument to King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, on Boston Common. It depicts a famous photo of the couple taken just after King found out he had won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. “I fought really hard to have Coretta Scott King included in the monument,” Terry says. The couple met in 1952, when King was a graduate student at Boston University. Designed by artist Hank Willis Thomas, the sculpture was five years in the making, a process that included a design competition and public comment sessions, focusing especially on the city’s Black neighborhoods.

But the unveiling sparked a social media frenzy that quickly turned ugly. Some commenters noted that from certain angles, the tangle of arms and hands looked pornographic. Others called the artwork racist or whitewashed, assuming that African Americans weren’t part of the decision-making, even though most of those involved, including the artist, were Black. Outlets worldwide picked up the story. Comedian Leslie Jones mocked the sculpture on The Daily Show.

“Did [The Embrace] fix everything? Of course not. But it is setting in motion, I think, a new way of thinking about Boston.”

“I think what happened,” Terry says, “is that it just ran headlong into an old narrative about Boston, that there are essentially no Black people here, and the ones who are here have no power; they’re beleaguered and disorganized and mostly irrelevant.” (It ran into even older ideas, he adds, about race. “Race is a highly valent form of difference, and one where people work out so many of their ideas about purity and impurity, safety and danger, the animal and the human,” he says. “Sex is always a big part of that, and given my training, I shouldn’t have been surprised.”)

But since that rocky start, the monument has become a community gathering spot. Terry serves on the board of a nonprofit, Embrace Boston, that hosts a speaker series and an ideas festival, plus other events and celebrations. “It’s become a symbol of Black competence, a way for people to make connections and break down fear, break down alienation, break down exclusion,” he says. “Now, did it fix everything? Of course not. But it is setting in motion, I think, a new way of thinking about Boston.”

The saga of The Embrace—the controversy and backlash, the subsequent reappraisal—feels in a way like a microcosm of what Terry has been writing about all along. This sculpture is not the kind of monument we’ve been taught to expect: a solitary hero in a symbolic pose on a literal pedestal.

Instead, it’s something more human and relatable—a real moment in a complex individual’s life, a universal gesture of connection—but those attributes, paradoxically, seemed to make the sculpture harder to grasp. Perhaps because romantic narratives are difficult to let go.