Most European languages share a common ancestry: you can hear it in the echoes between the English mother, Spanish madre, Russian mat’, German mütter. But then there are äiti, anya, ema—the words for “mother” in Finnish, Hungarian, and Estonian.

These are the Uralic languages, whose roots, grammar, and rhythm are nothing like those of their Indo-European neighbors. Stranger still, they bear striking similarities to languages spoken not in Europe, but far to the east, in Siberia, Central Asia, and Mongolia. Where did the speakers of these enigmatic languages, scattered in isolated pockets throughout Europe, come from?

For centuries, linguists have tried to solve this mystery. One dominant theory placed their homeland near Russia’s Ural Mountains, the language family’s namesake. But new research from Harvard scientists points somewhere even further east: Yakutia, a region in northeastern Siberia on the same longitude as eastern China, Japan, and Korea.

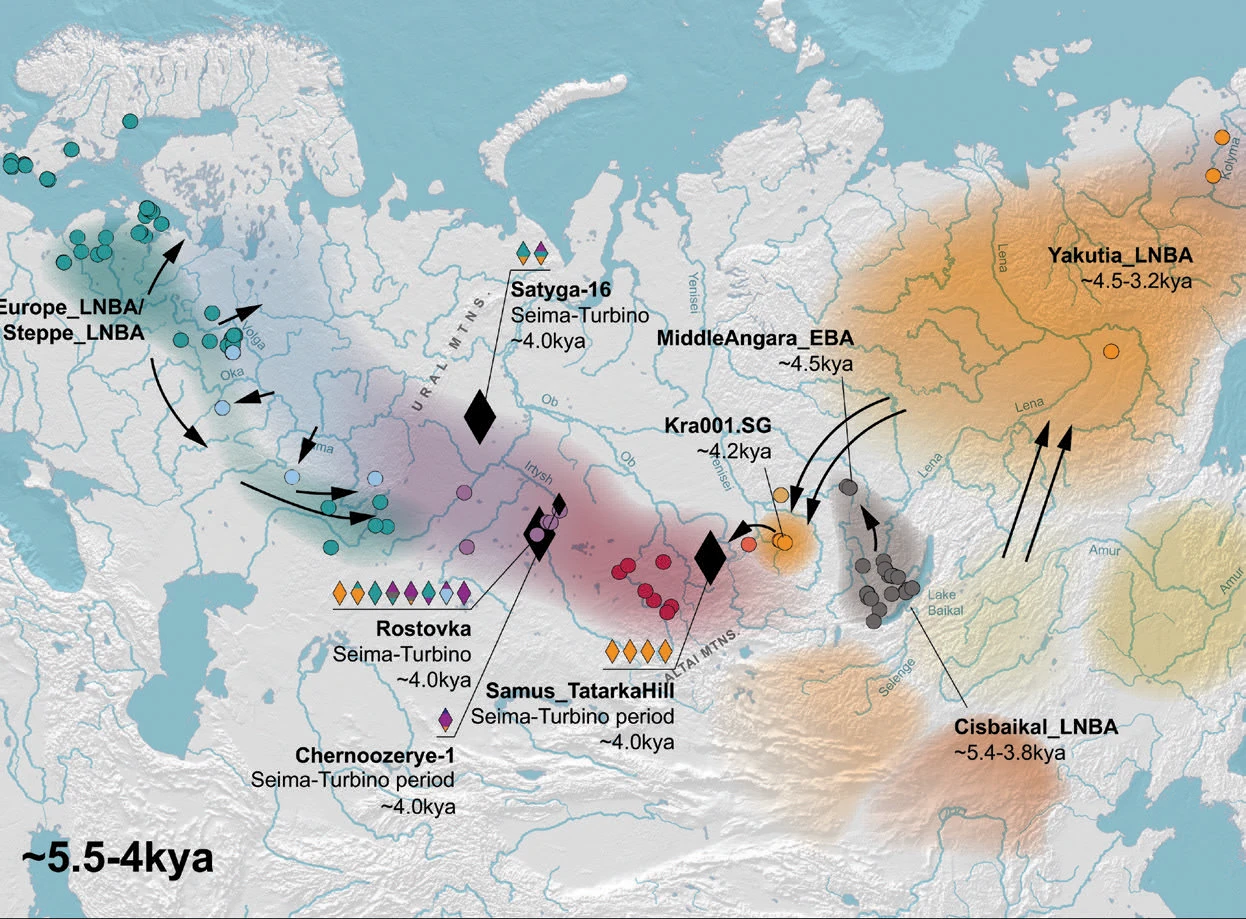

By analyzing over 1,000 ancient DNA samples, the team discovered a unique “genetic signature”—a distinctive set of DNA variations—shared exclusively by Uralic-speaking populations. This genetic pattern first appears, in unmixed form, in 4,500-year-old samples from Yakutia. From there, the DNA record shows, those populations spread westward into modern Europe.

NATURALEARTHDATA.COM/DOWNLOADS/10M-RASTER-DATA/10M-GRAY-EARTH/

Tracing language spread through DNA isn’t new. Earlier this year, professor of genetics and human evolutionary biology David Reich—who also co-authored the work on Uralic languages—used this method to map the origins of Indo-European languages, spoken today by more than 40 percent of the world population. But because Uralic languages are far less common, they are also harder to trace: there is just less DNA to work with.

Co-lead author Alexander Mee-Woong Kim ’13, M.A. ’22, has helped to change that. Beginning in 2015, he journeyed to Siberia to collect DNA samples from ancient human skeletal remains. With 180 new samples gathered during his fieldwork, researchers were finally able to piece together the ancient history of the Uralic language family.

“For many people in the U.S.,” Kim says, “Siberia feels like a distant, remote place with small populations, far away from everything.” But these findings tell a different story, showing the region is “a nexus out of which things emerge…a region where world-transformative processes originated.”

The DNA evidence also sheds light on how Uralic languages spread—and why they now survive only in scattered pockets. The first westward movement of Uralic-speaking hunter-gatherers was around 4,000 years ago, during the Seima-Turbino phenomenon: a Bronze Age network of trade, travel, and metalworking that co-lead author Tian Chen (T.C.) Zeng, Ph.D. ’25, likens to a “proto-United Nations.” Through this vast cultural exchange, diverse populations, including early Uralic language speakers, came into contact.

After Seima-Turbino, Uralic language speakers moved west in larger numbers. “The Uralic genetic signature pushed westwards, all the way to the Baltic Sea,” says Zeng, who studies human evolutionary biology.

But over time, much of that ancestry faded. Today, Estonians carry about 1 to 2 percent of Yakutia-related ancestry in their autosomal DNA (which includes all chromosomes except sex chromosomes). Finns have a higher proportion, around 10 percent.

But when scientists examine these populations’ sex chromosomes, they find that roughly 50 percent of Finnish and Estonian men have a Y chromosome that traces back to early Uralic language speakers. This suggests a pattern called “sex-biased migration,” says Zeng. Men were likely the primary drivers of migration and had children with women from other populations. Over generations, this diluted the Yakutia ancestry in the overall DNA inherited from both parents, but the populations’ Y chromosomes—passed only from father to son—remained largely Yakutian in origin.

Hungary, where the population has almost no Yakutia ancestry, presents a more dramatic case. In the ninth and tenth centuries, Uralic-speaking Magyar conquerors arrived in the region and imposed their language, but didn’t intermix with the indigenous population and therefore left little genetic trace. This is an example of “an elite replacement event,” says Reich: small groups imposing their language through “political power.” Such an event was rare in ancient history, he says, but far more common today: many Americans, for instance, speak English as a first language without having English ancestry.

The scattered presence of Uralic languages today hints at both a broader and more connected reach across northern Eurasia. Over time, however, Indo-European-speaking peoples gradually redrew the linguistic map. “The pattern you see with Uralic languages—little islands surrounded by a sea of Indo-European languages,” Reich explains, “is usually what happens when there’s a subsequent language expansion.”

Beyond genetics and archaeology, the story of the Uralic language speakers is also one of resilience and adaptability, says Kim. Though they began as a relatively small group, their cultural and linguistic legacy remains. “I have the strong sense that early Uralic speakers were not merely in a fortuitous place geographically and ecologically,” Kim says, “but they had a remarkable ability to flourish amidst dramatic collisions of political forms, social structures, and worldviews.”