October, the month when things creep and crawl, is a fitting time to meet one of nature’s strangest hunters.

Imagine you’re a termite inching across the jungle floor in Singapore. From the shadows, something strikes—twin jets of glue entrap you, Spider-Man style. The monster then slurps up its own protein-rich slime before devouring you, its immobilized victim, whole.

This terrifying predator, ranging from two to ten centimeters in length, is the velvet worm. Members of the ancient phylum Onychophora, velvet worms have fascinated scientists for centuries. Their soft, eponymously velvety skin and vivid colors conceal a secret weapon: a built-in glue “cannon.”

A new exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, “Velvet Worms: A Fierce Hunter with a Secret Weapon,” turns a spotlight on the creatures. Curated by Gonzalo Giribet, a professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and the director of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, the exhibit delves into the worm’s ancient biology—and includes Giribet and his team’s discovery of a new species in Singapore this year.

Found scattered across regions once joined by the supercontinent Gondwana, velvet worms are living clues to Earth’s evolutionary history, because they have remained relatively unchanged for the last 300 million years. The first velvet worm was described in 1826 by Reverend Lansdown Guilding, who mistakenly classified it among Caribbean mollusks. Today, scientists recognize it as a living link between arthropods and tardigrade, two of the most successful and enduring animal lineages on Earth.

Giribet’s recent discovery is part of a broader effort to map velvet worm diversity in a region teeming with life but still underexplored. “Large parts of Southeast Asia are tropical like the Amazon,” Giribet says, “but the islands are so fragmented that the research communities studying them remain isolated.” This creates barriers to collaboration and information sharing, so that knowledge tends to remain in silos between islands.

Many species are also difficult to distinguish by sight, as their differences lie in minute morphological details. Advances in DNA sequencing, however, are changing that. Giribet’s team used genetic tools to identify the yet-unnamed species.

The new discovery began with a photo. Researchers spotted images of an unknown velvet worm on the biodiversity platform iNaturalist, prompting an expedition funded by Harvard. “We didn’t get permits to collect where it was first reported, in Singapore’s Central Catchment area,” Giribet recalled, “but we did obtain access to a small island called Pulau Ubin. There, we found many velvet worms.” The team later compared their specimens with those in the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum and discovered, through genome sequencing, that they represented distinct species.

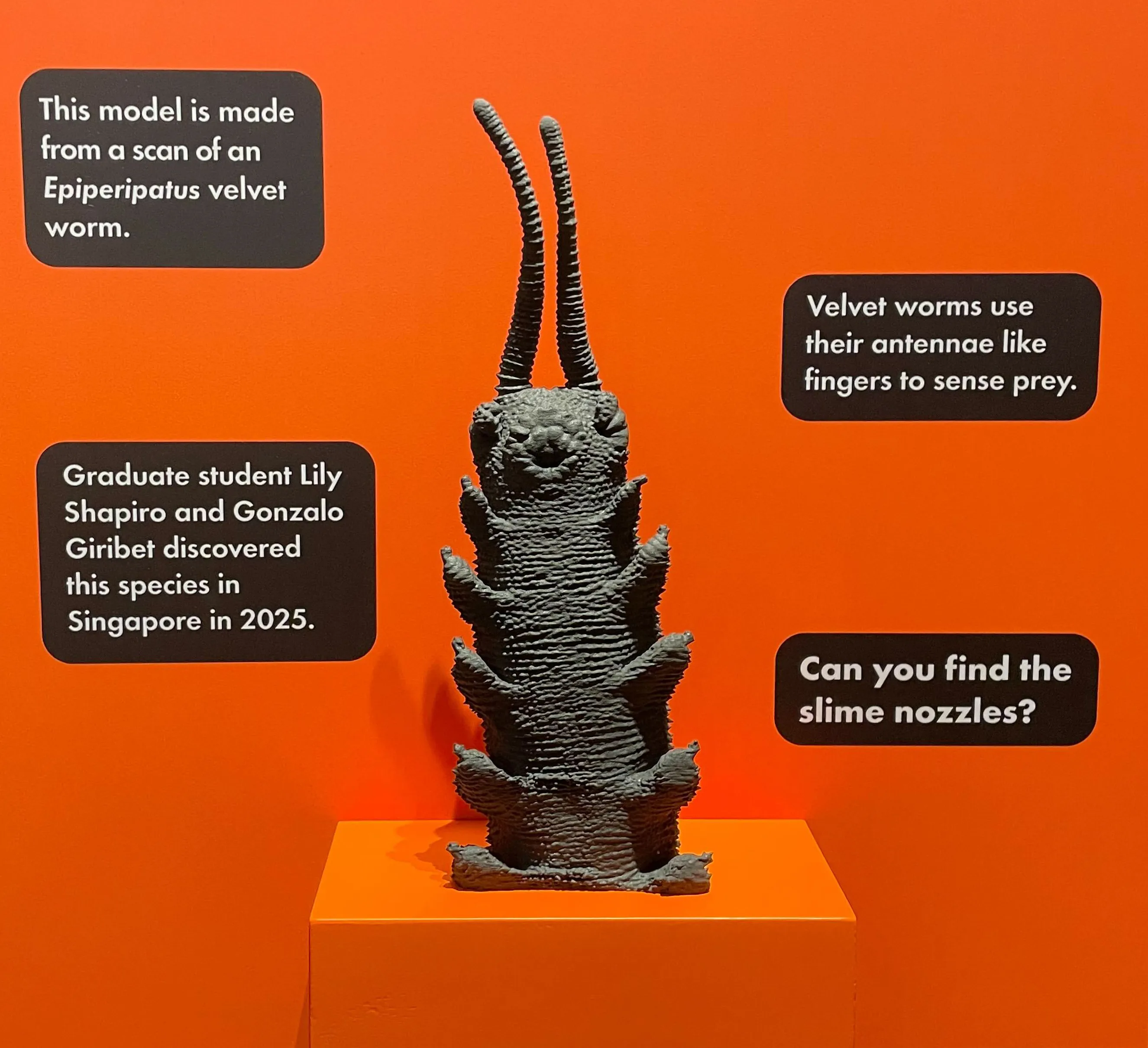

At the center of the new Harvard Museum of Natural History exhibition stands an oversized, 3D-printed model of the team’s newly discovered species, reconstructed from CT scans. Surrounding it are photographs of other velvet worm species from around the world, including the translucent Speleoperipatus spelaeus from Jamaica, the brilliant blue Peripatoides aurorbis from New Zealand, and Peripatus juliformis from St. Vincent, one of the first ever described.

Up close, the velvet worm’s name proves apt. Its skin is covered in tiny papillae, or small bumps fringed with bristles sensitive to touch and smell (not unlike the surface of a tongue). Beneath that soft exterior lies a tough chitinous cuticle that must be shed for the animal to grow, a trait shared with insects and crustaceans.

In video displays, exhibit visitors can watch the creatures in action. With a sudden, muscular flex, the velvet worm ejects twin jets of its glue, instantly entangling its prey. The adhesive is produced in an internal gland nearly as long as the animal itself. According to Giribet, the glue has strong potential as a biomaterial that could be studied and adapted for other applications, composed of a powerful liquid polymer that could one day inspire new materials or adhesives.

Ongoing research at Harvard led by Giribet and his students and colleagues focuses on the genetics, genomes, and biogeography of velvet worms. “Studying velvet worms offers a unique opportunity to work in some of the most remote and beautiful forests in the world,” Giribet said.

As the continents have drifted and reformed over millions of years, velvet worms have moved with them. By comparing their genomes, researchers can reconstruct the breakup of Gondwana and trace how the species dispersed across the Caribbean, where nearly every island except Cuba harbors its own unique velvet worm.

Under the lights of the Harvard galleries, the velvet worm’s replica gleams, frozen mid-hunt. Boo, it seems to say. Boo, indeed.