History or fiction? The line dividing these disciplines is not as impervious as one might think. Both pursue truths but make divergent claims about the stories they tell and the methods used to tell them. Like novels, histories are narratives—with a beginning and an end, and a lot left out in between. And by showing what may have been, or what could be, fiction can reveal truths that reality obscures.

From psychological mysteries and a history of medical imaging to studies of language and a guidebook on estate planning, the following titles challenge us to rethink our versions of the past, present, and future. They pursue reality by different means: some revisit tradition while others blur the confines of genre or resist the pitfalls of dichotomy.

Should you listen to them? It depends. How well each of the following authors convinces us of their truth has less to do with elevating tastes than with expanding perspectives. Whether or not these titles transform long-held beliefs or inspire empathy ultimately resides in the realm of imagination.

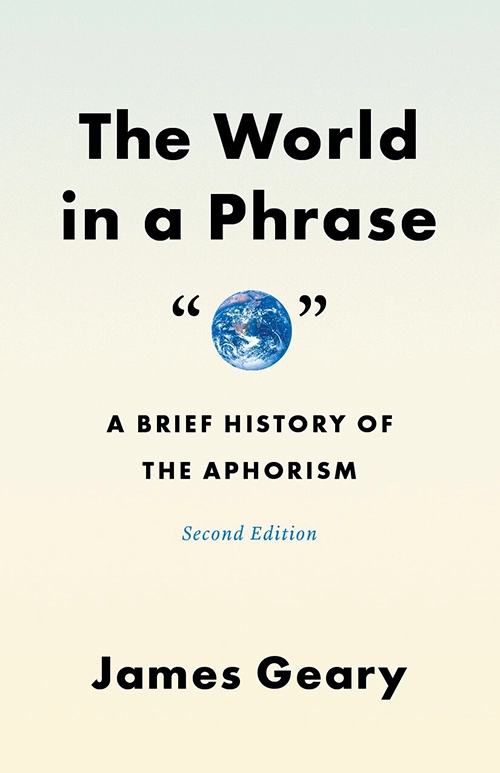

The World in a Phrase: A Brief History of the Aphorism, second edition, by James Geary, NF ’12 (University of Chicago, $22.50 paperback).

Aphorisms, ancient and inspiring, are alive and well in the digital age, where our ever-shrinking attention spans reward the short and sweet. Two decades after its first publication, the updated World in a Phrase includes 26 new aphorists from throughout history and brings social media into the conversation through viral posts, like those of the popular internet nihilist Eric Jarosinski: “Peace: what everybody’s fighting for.” Not every meme or hot take qualifies as an aphorism, warns Geary, a lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School. The difference lies in the depth of the bite-sized lesson: “Aphorisms deliver the short sharp shock of an old forgotten truth.”

The Future of Seeing: How Imaging Is Changing Our World, by Daniel K. Sodickson, M.D. ’96 (Columbia, $35).

Do images hold the key to the future of medicine, and will access to this technology be democratized? What role will AI and deep learning play in monitoring health? Before skipping to the answers, Sodickson—a medical-imaging pioneer and former Harvard Medical School faculty member—takes us back, way back, to the evolution of eyes and the history of medicine. From his walk through the development of microscopes and telescopes to X-rays and the medical imaging industry, Sodickson instills an appreciation for the “millennia of innovation” in our quest for new ways of seeing.

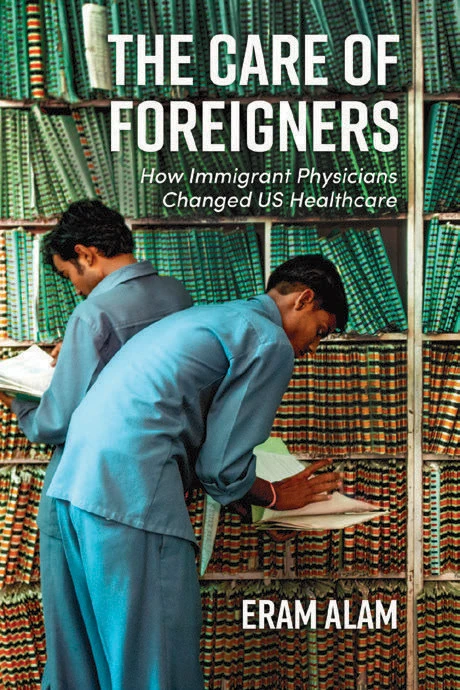

The Care of Foreigners: How Immigrant Physicians Changed US Healthcare, by Eram Alam (Johns Hopkins, $64.95 paperback).

From the Cold War’s Hart-Celler Act in 1965 to the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. has relied on foreign-born physicians, many from South Asia, to fill the gaps in its medical labor force. Eram Alam, assistant professor of the history of science, analyzes the country’s dependency on foreign medical labor and reframes the conversation about physician migration, exposing the global implications and ethical dilemmas of labor moving from resource-poor to resource-rich countries. Using data and firsthand accounts from foreign-born physicians, Alam reveals discriminatory labor abuses and barriers to licensure, while examining this group’s economic and social mobility.

The Rembrandt Heist: The Story of a Criminal Genius, a Stolen Masterpiece, and an Enigmatic Friendship, by Anthony M. Amore, M.P.A. ’00 (Pegasus Crime, $29.95).

Amore has spent his career chasing down prized artworks stolen by criminal masterminds—as head of security for Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, he leads ongoing efforts to retrieve 13 paintings stolen from the museum in a famed 1990 heist. Here, Amore shares a redeeming sketch of his unlikely friend Myles Connor, a notorious art thief who absconded with a Rembrandt from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 1975 and afterward led a life of unexpected nuance.

The Limiting Principle: How Privacy Became a Public Issue, by Martin Eiermann ’10 (Columbia, $37 paperback).

Privacy is elusive, not just as a commodity but also as a concept. Yet, it’s constantly invoked in debates ranging from Big Tech and government overreach to reproductive rights and digital-age childhoods. Eiermann examines privacy’s rise to prominence and how it shifted from a concept concerning the home and societal norms to “a public issue and a limiting principle of modern American society” with implications in government, law, and beyond.

The Other Rooms, by Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, translated by William Tamplin, Ph.D. ’20 (Darf, $18.99).

A nameless protagonist is abducted from the streets of an unnamed city. For reasons unknown, he is moved from room to room of an obscure compound where captors wear many disguises and senses betray. Though shrouded in mystery, the nightmares of this beautiful, psychological novel by Palestinian-Iraqi modernist Jabra Ibrahim Jabra (who completed a Harvard fellowship in literary criticism in 1952-54) feel urgent in their portrayal of oppression as both isolating and collective: it is happening all around us if we care to look. This is the second Jabra book that Tamplin, a communications officer in the U.S. Marine Corps with a doctorate in comparative literature, has translated. May there be more to come.

The Price of Democracy: The Revolutionary Power of Taxation in American History, by Vanessa S. Williamson, Ph.D. ’15 (Basic, $32).

How much does democracy hinge on the ability of a government to tax citizens? It turns out, a whole lot. “When it comes to contestation over democracy, taxes are both the battleground and the war,” writes Williamson. With clarity and concision, she unpacks the history and power dynamics of this enduring obligation, tracing three prevailing arcs of this war: taxation for a republic, taxation for Black liberation, and taxation for the general welfare.

My Mother’s Money: A Guide to Financial Caregiving, by Beth Pinsker ’93 (Crown Currency, $21 paperback).

Sometimes hard truths are the most essential to face head-on, as we learn from MarketWatch columnist Pinsker’s new playbook for financial caregiving. Practical and personal—Pinsker opens up about her own mother’s care—this guide is filled with advice from experts and in-the-trenches caretakers. It covers misconceptions about Medicare, the importance of power of attorney, and facets of estate planning. How do we protect our agency as we age? How can caregivers navigate burnout and advocate without infantilizing? To help, Pinsker includes conversation prompts for tricky topics, to-do lists in every chapter, and templates for essential care-planning documents.

The Award, by Matthew Pearl ’97 (Harper, $30).

The novel opens with an intriguing note from its author: “Some of this happened.” What follows is a thriller where catharsis and darkness go hand in hand in the rat race that is literary ambition. Set in Cambridge, the story finds its protagonist in a struggling writer navigating the pitfalls and pretenses of Boston’s writing scene circa 2010 (think “Bad Art Friend” infamy). More than one exchange between characters will leave you wondering where exactly the lines between fact and fiction are blurred. And Pearl, known for both narrative nonfiction and historical fiction, seems a natural choice to do the blurring.

Kill Talk: Language and Military Necropolitics, by Janet McIntosh ’91 (Oxford, $19.99 paperback).

Euphemisms of battle and brutal bootcamp commands form “kill talk,” a linguistic infrastructure of military violence examined here by McIntosh, an anthropologist. Kill chants (literal shouts of “Kill!” during training) and popular nicknames like “maggot” dehumanize enemies and soldiers alike; others like “buttercup” and routinely used homophobic slurs feminize to show weakness as much as they isolate to “strengthen.” A warning: the often offensive and profane language remains unfiltered and intact in this ethnographic study to both capture reality and honor the requests of interviewees. The result is a viscerally dark yet necessary confrontation of kill-or-be-killed military culture that McIntosh argues helps normalize violence in American culture and facilitate war.

Declaring Independence: Why 1776 Matters, by Edward J. Larson, J.D. ’79 (W.W. Norton, $29.99).

This book begins with a question: How, in seemingly one year, did the 13 colonies go from a population of generally content British subjects to a hotbed of rebellion in which a majority of colonists favored independence? Ahead of next year’s 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Larson delivers a user-friendly distillation of the major events and ideas in that pivotal year. While less immersive than Larson’s narrative histories, Declaring Independence is no less focused on the key details of a historical moment while signposting its enduring legacy in American culture.

Better Judgment: How Three Judges Are Bringing Justice Back to the Courts, by Reynolds Holding ’77 (University of California, $29.95).

Unlike those of politicians, the names and lives of U.S. federal judges—meant to be the last line of defense against unchecked power and injustice—often remain obscure unless they end up on the Supreme Court. Their decisions, however, impact generations. Here, Holding, a journalist, goes behind the bench into the lives of Jed Rakoff, Martha Vázquez, and Carlton Reeves, three dynamic federal judges who embody his case for a strong, intact judicial branch that keeps oligarchies at bay while protecting the constitutional rights of individuals. Along the way, Holding traces how their ability to do each of these jobs has been eroded by both the left and the right in recent decades and the dangers that result.