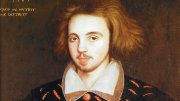

He was a radical, the inventor of blank verse, a master of internal monologue, and a victim of murder. This was the English playwright Christopher Marlowe, a contemporary and rival of William Shakespeare—and perhaps the Bard’s key creative influence.

At 14, young Marlowe—the son of a poor Canterbury cobbler—won a scholarship to the prestigious King’s School, becoming the first in his family to receive a formal education. He excelled, went on to the University of Cambridge, and there studied the great works of antiquity, from Virgil’s Aeneid to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Where his classmates saw musty mandatory reading, Marlowe found something else: worlds of ecstatic violence and erotic excess, of vengeful outcasts and capricious gods, worlds that upended the Christian moral order in which he was raised.

After graduation, Marlowe faced an uncertain future—unlike his wealthy classmates, his education didn’t secure for him a place in society. So, he decided to take a risk, moving to London to try his hand at an unstable, disreputable profession: writing for the stage.

When Marlowe was born in 1564, says Stephen Greenblatt, the Cogan University Professor of the Humanities, England was still stuck in the Middle Ages, even as the Renaissance bloomed on the continent. Public entertainment revolved around bearbaiting and hangings; poetry was weighed down by moralizing and clumsy rhymes; brutal censorship stifled any art that challenged the crown’s authority.

By the time Marlowe died in 1593, at just 29 years old, England was in the midst of a cultural and intellectual flourishing. Greenblatt credits Marlowe with sparking this transformation. In a new book, Dark Renaissance: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Christopher Marlowe, Greenblatt—one of the world’s foremost Shakespeare scholars—argues that Marlowe didn’t merely precede Shakespeare, he made Shakespeare’s career possible.

“It was Marlowe who cracked something open,” Greenblatt says, “and enabled Shakespeare to walk through—how should we say?—over his dead body.”

Marlowe’s story, Greenblatt adds, is also relevant to many of academia’s current preoccupations. He was a “first-gen” student who glimpsed radical possibilities in the supposedly conservative texts of “great books courses.” He faced a “vocational crisis” familiar to many humanities students today—and pursued his passion despite the risk.

That career began with Marlowe’s debut play, Tamburlaine the Great, written in 1587 or 1588. “Virtually everything in the Elizabethan theater,” Greenblatt writes, “is pre- and post-Tamburlaine.”

Part of the play’s shock value lay in its plot. Loosely based on the rise of the fourteenth century Central Asian conqueror Timur (also known as Tamerlane), Tamburlaine the Great tells the story of a Scythian shepherd who ascends from obscurity to become a dominating tyrant. The violence is unrelenting, and the ambition unchecked: Tamburlaine faces no moral comeuppance for his pride. This rags-to-riches arc may have mirrored Marlowe’s own desires, Greenblatt writes—and defined many of the other outsider characters Marlowe would go on to write.

But the play’s most revolutionary element was formal: the use of “this hallucinatory blank verse, which Marlowe basically invented,” Greenblatt says. Marlowe’s characters spoke in unrhymed iambic pentameter—“elegant, musical, and forward-thrusting,” Greenblatt writes—which gave English drama a new expressive register.

Before Tamburlaine, English playwrights were trapped in stiff structures such as Poulter’s measures—couplets in which 12-syllable iambic lines rhyme with 14-syllable iambic lines. Blank verse enabled Marlowe’s characters to sound like they were “actually speaking English,” Greenblatt says, dramatized by some structure, but still alive. Shakespeare would come to rely heavily on blank verse in his own work.

Doctor Faustus marked the first time “a powerful, complex inner life” was represented on the stage.

A few years later came Doctor Faustus, first performed in 1594. It was Marlowe’s most famous play and the first dramatization of the Faust legend, in which a scholar makes a deal with the devil, trading his soul for magical powers. This work, Greenblatt argues, marked the first time “a powerful, complex inner life” was represented on the stage.

Before Marlowe, English theater externalized psychology through allegory: morality plays populated by characters such as Pride and Shame. In Doctor Faustus, by contrast, Marlowe relies on soliloquy and dialogue about the characters’ internal states. “It was from Doctor Faustus that the author of Hamlet and Macbeth learned how it could be done,” Greenblatt writes.

Marlowe’s life ended as dramatically as one of his plays: he was stabbed to death in a tavern in Deptford. Officials claimed the death resulted from a quarrel over a dinner bill—but Greenblatt points to a more complicated story. While still a student at university, Greenblatt writes, Marlowe was likely recruited as a spy for Queen Elizabeth’s secret service, possibly to monitor Catholic dissidents or plots against the crown.

But over the years, Marlowe drew scrutiny for his radical ideas and was accused at times of atheism—a grave offense in Elizabethan England. Greenblatt believes that Marlowe was killed for his beliefs, possibly on orders carried out by an “overly zealous servant” of Queen Elizabeth herself.

To Greenblatt, Marlowe’s life serves as a reminder of how repressive Elizabethan England was: “It was basically wise to keep your head down, unless you wanted your head to be chopped off.” Marlowe didn’t and paid the price. Shakespeare was watching, Greenblatt argues, and learned he had to be more careful. But Shakespeare’s blend of conservatism and radicalism was only possible because Marlowe had first ventured too far. Shakespeare relied, Greenblatt writes, on Marlowe’s legacy of “reckless courage and genius.”

And Greenblatt believes Shakespeare was aware of his debt. Greenblatt’s Dark Renaissance ends with a line from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, a reference to Marlowe’s mysterious death in that small tavern room in Deptford: “When a man’s verses cannot be understood…it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.”