Five whitewater kayakers gather on the banks of Peru’s Paucartambo River to deliberate whether to paddle through an especially perilous section of rapids or carry their boats around it. They’re halfway through a 17-day expedition exploring one of the remotest parts of the river, which flows from the Andes down through the Amazon. In the 250 miles they’re paddling, it drops a staggering 13,000 vertical feet.

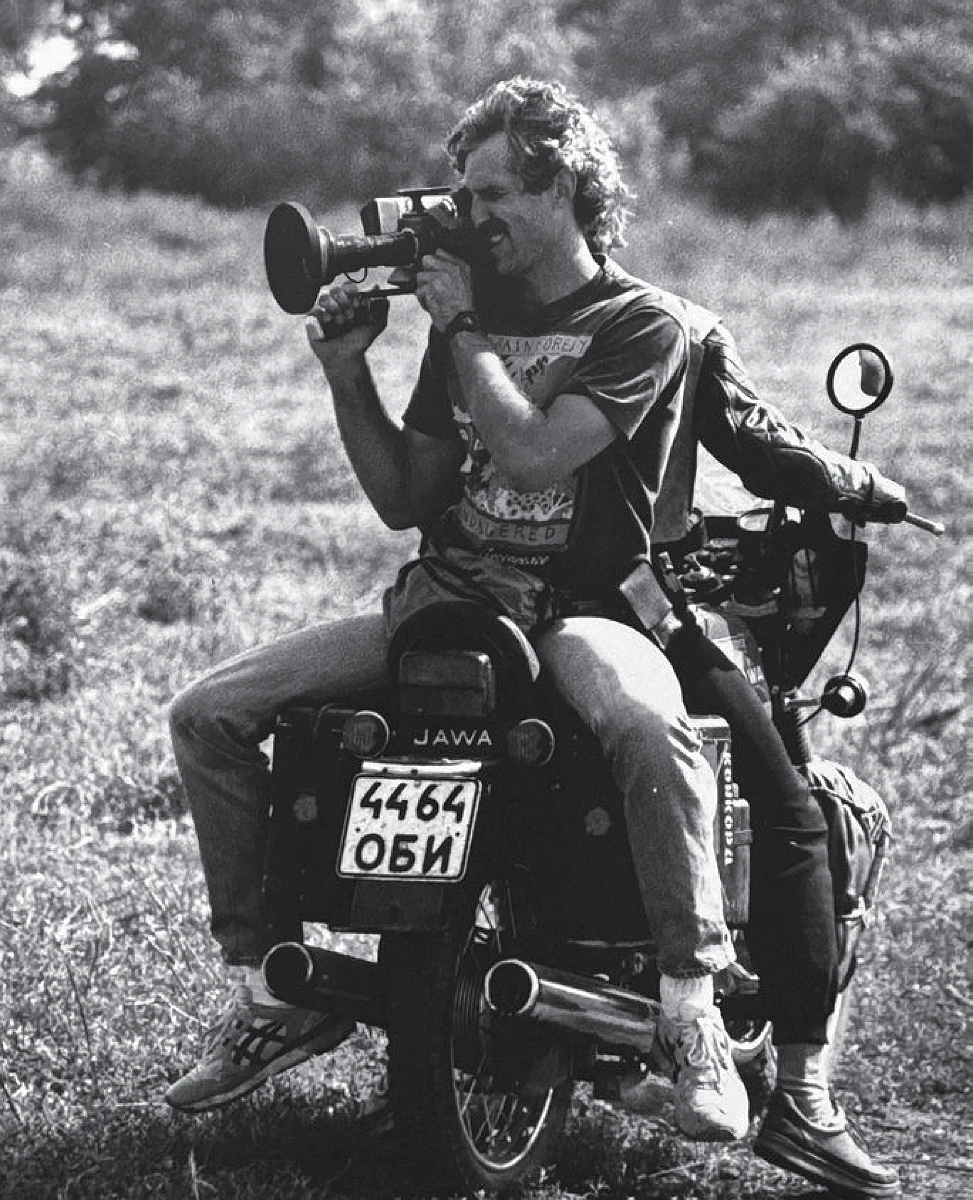

All but one decide to try the rapid. From a perch on a rock just above the water, filmmaker John Armstrong ’74 captured the scene in Paucartambo: The Rest of the River (1987). One by one, the kayakers slide off a ledge into the furious churn below, and Armstrong’s camera follows each as their boats seesaw through the boulder-strewn river, paddles pushing hard against the current.

For nearly 40 years, this was Armstrong’s art: pulling human stories from strenuous, uncertain journeys in faraway places. He and his cameras have trekked through the Amazonian jungle, the Bering Strait, and the ice mountains of Antarctica. In 1989, just before the Soviet Union fell, Armstrong joined a group of American kayakers on a rare expedition down the Bashkaus River in southern Siberia. Their Soviet companions traveled in catamaran rafts that they built on the spot, Armstrong recalls, from freshly-felled alder trees and flotation tubes sealed with wine corks. Working with outlets including the Discovery Channel, ESPN, National Geographic, and the Outdoor Life Network, Armstrong—who often wrote, directed, and produced his own films—has also followed hang gliders in the Andes and American cowboys visiting nomadic horsemen in Mongolia. Extreme environments, he says, make the human spirit more visible. “Partly,” he explains, “that’s what I’ve wanted to capture.”

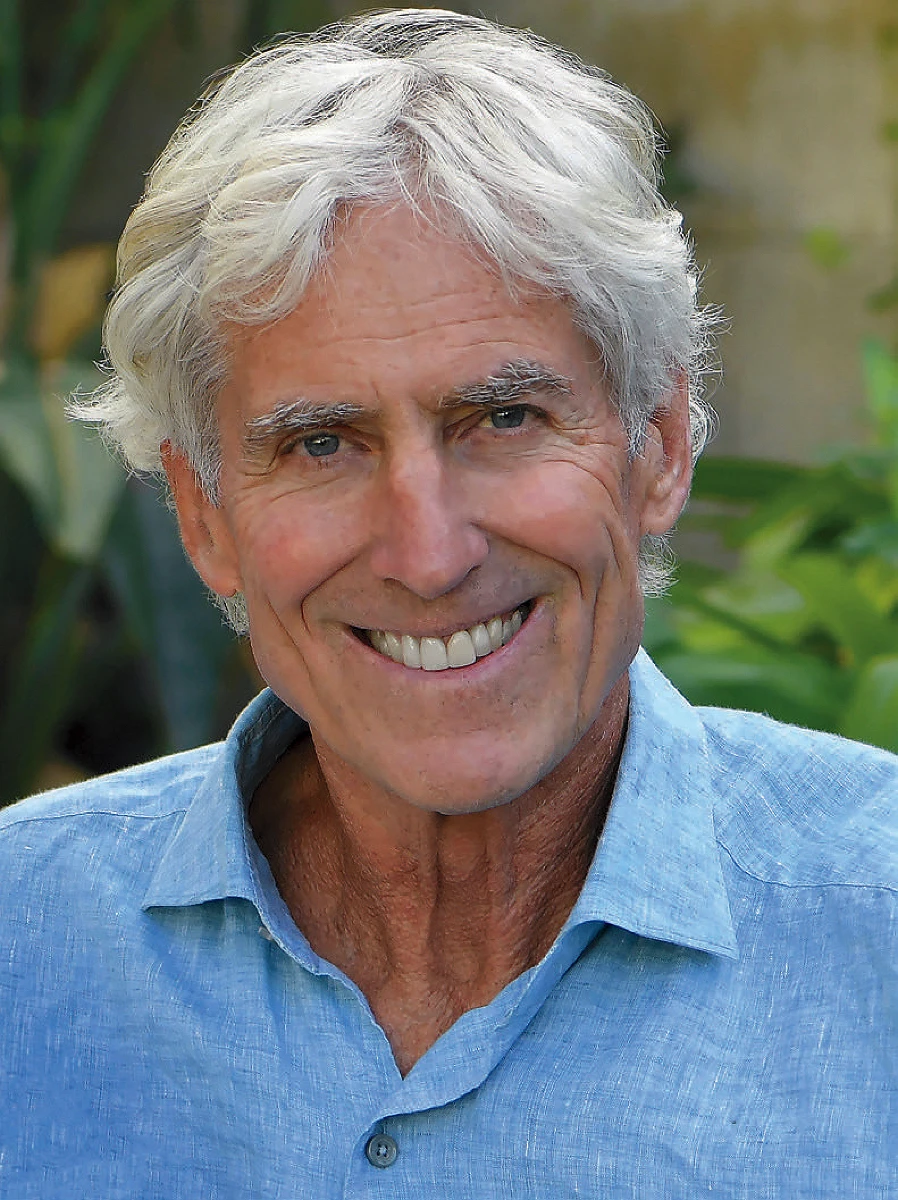

Earlier this year, Armstrong, who retired in 2020, received a lifetime achievement award from the Society of Camera Operators, for a career that spanned not just documentaries but also dozens of reality television shows, many involving outdoor competitions. He won three Emmy awards—the first for Mountain of Ice, a 2001 PBS Nova documentary, where he was director of photography. It followed a small team of scientists and mountaineers (including expert climber Conrad Anker and writer Jon Krakauer) as they made a grueling, dangerous climb up a previously unexplored face of Vinson Massif, the highest peak in Antarctica, to gather climate and glacier data. The temperature dropped to 35 degrees below zero, with 60 mile-per-hour winds. “I had to figure out how to keep the cameras warm and the batteries functioning,” Armstrong says. The resulting film is stark but gorgeous, with the climbers at times silhouetted against a vast white landscape, inching their way upward as snow blows wildly off the massif’s plateau.

Growing up in San Marino, California, Armstrong learned skiing and surfing, and later football, which he played for three years at Harvard. But he took an interest in film as an undergraduate. A documentary filmmaking course with anthropologist and auteur Robert Gardner ’48, A.M. ’58, the longtime director of the Harvard Film Study Center, was transformative, as was a class on the surrealist director Luis Buñuel. Books by Ken Kesey and John Steinbeck sparked a lifelong interest for Armstrong in people living on the edges of society. At Harvard, he made a documentary about a charismatic, troubled homeless man called “Satan,” whom Armstrong had met while working at Boston’s Pine Street Inn shelter. As a part-time night lobby manager, he would sit up for hours, listening to residents’ stories. “In those years,” he says, “I knew practically all the homeless men in Boston.”

After college, he moved to Utah to teach high school. Filmmaking remained on his mind, though, and after a chance meeting with Robert Redford at a Harvard lecture, he spent a summer working at the Sundance Institute in Park City, immersing himself in the work of independent filmmakers. He also learned whitewater kayaking—and that was when something clicked. Before long, he was in Peru, scouting the Paucartambo for what would become his first film, Paucartambo: Inca River (1986). He produced it himself, and when National Geographic picked it up for broadcast, Armstrong’s career took off.

The thread connecting much of the work that followed isn’t just improbable feats of strength and stamina—it’s Armstrong’s abiding interest in people on the margins. That describes his “adventure-athlete” protagonists, who don’t quite fit into regular society, as well as the people they encounter along their journeys. In the Paucartambo films, one of the most vivid characters is a banana and yucca farmer who ekes out a livelihood beside the river despite frequent floods. In another film, Cliff Mummies of the Andes (2001), which follows an archaeological team searching for preserved gravesites of the Chachapoya people, Armstrong turns his camera to the present-day villagers who are kin to the 1,000-year-old mummy the archeologists find. (After DNA testing, the researchers return the mummy to the village.)

And in Curtain of Ice, a 1990 documentary about a paraplegic kayaker from California and his quest to paddle across the Bering Strait—a journey that turns harrowing when the kayakers get blown far off course and stray into Soviet territory—one of the more emotional scenes centers an Inupiat elder. For 40 years, the Iron Curtain had separated Indigenous people living in Alaska from those in the Soviet Union, cutting off family members and communities. The Alaskan elder, Alice, along with several younger Inupiat men, joins the kayakers’ expedition to look for relatives. And on the other side of the border, she finds one. Armstrong keeps the camera rolling as Alice, holding back tears on the frigid beach, takes off her heavy parka to embrace a long-lost cousin.

One unfinished film still haunts him. Living in Lima, Peru, during the 1980s, Armstrong became engrossed in the world of young street thieves—homeless orphans and runaways who swarmed passers-by, stealing their possessions and sometimes literally undressing them. Called “Piranhas,” they came to trust Armstrong, and from his apartment above an open-air market he watched them work. The images he captured are shocking—one child steals an oil filter from a moving car; others attack a vendor in broad daylight. Bits of the footage made it into a CBS Evening News broadcast, but he never got funding for a documentary. “I tried to follow up on some of their lives years later,” he says. One of the lead Piranhas was dying of tuberculosis, another had lost a leg after being shot by police. “I still dream of returning someday to film follow-ups with survivors,” says Armstrong, hungry for one more glimpse beyond society’s edges.