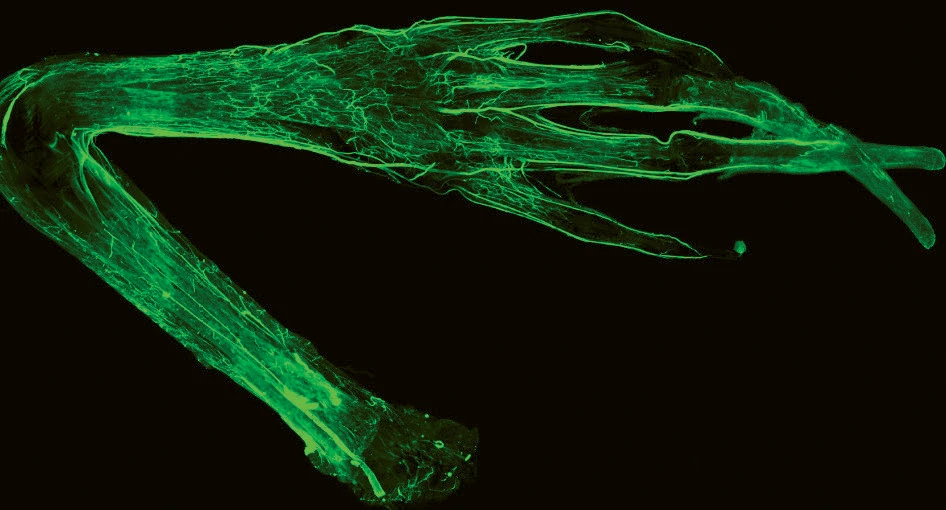

An axolotl is a salamander with a superpower: it can regrow its limbs. When a predator chomps off its leg or it loses an appendage in an accident, a new one will quickly take its place.

Many scientists would like to know how the axolotl does this and whether it’s possible to stimulate lost limbs to regrow in humans, too. In recent decades, research has focused on how cells around an axolotl’s injury site reorganize to kick off limb regeneration. But in fact, the animal’s whole body jumps into action, as regenerative biologist Jessica Whited and her colleagues describe in a study recently published in Cell. The molecular marks of limb amputation were evident in “basically all the places we looked,” Whited says, including in unamputated limbs.

Amputating an axolotl’s arm or leg causes cells to proliferate in distant parts of the body as well as near the wound.

Focusing on the whole animal is not exactly new—decades ago, scientists studied how chemical messengers that travel throughout the body influence regeneration. But most recent work has focused on the cells nearest to the injury site, partly because they’re known to be the source material for new limbs, says Whited, an associate professor of stem cell and regenerative biology. She and her colleagues widened their focus after they noticed that amputating an axolotl’s arm or leg causes cells to proliferate in distant parts of the body as well as near the wound.

“There are two obvious things to check as a way to spread information around the body,” Whited says: the circulatory system and the peripheral nervous system. The circulatory system may well be important, but Whited’s lab chose to focus on nerves, partly because classic experiments performed in the early 1800s already pointed to a role for the nervous system in regeneration.

Postdoctoral researcher Duygu Payzin Dogru, Ph.D. ’22, had, as a doctoral student at Harvard, led a team that undertook the delicate task of snipping axolotl nerves—some near an amputated limb, others in limbs that were intact. The team found that in all cases, these surgeries stopped the body-wide response to amputation. To narrow in on the specific molecule that carries information about amputations through nerves, Payzin Dogru treated axolotls with drugs that block various components of the nervous system. Noradrenaline—a neurotransmitter involved in the fight-or-flight response—turned out to be the messenger the researchers were seeking.

The research also showed a connection between the salamander’s regenerative process and its metabolic controls. Whited’s lab and others had previously discovered that a protein called mTOR, typically thought to regulate metabolism, is critical for axolotl limb regeneration. When the researchers blocked certain noradrenaline receptors in the salamanders, they prevented mTOR from being activated when a limb was amputated and stopped the limb from regenerating.

Showing that the response to amputation is body-wide opens up “a whole new area” in the field, says University of Florida professor and biologist Malcolm Maden (who was not involved in the study). The whole-body activation also has a peculiar consequence: in cases when an axolotl loses two limbs in quick succession, losing the first primes axolotls to regenerate the second lost limb faster, Whited’s lab found.

Scientists are not yet sure how axolotl cells at the site of injury know that they should begin forming a new limb. If those cells had formed other body parts prior to the injury, they may need to be “reprogrammed” before they can take on a new role. Human cells may not be capable of the same sort of reprogramming, Whited says.

At the same time, there are hints that human limb regeneration might one day be possible. The molecular and cellular pathways Whited’s lab is investigating in axolotls also exist in humans, and the limb buds from which arms and legs grow during human embryonic development bear some resemblance to blastemas, from which axolotls regenerate lost limbs.

“We’ve all done it once,” Whited says, referring to the process of growing a limb during development. “Why we can’t do it again later, on command, when the need arises, is a big question.”

There are also indications that mammals keep the ability to regenerate buried just below the surface. For example, scientists recently showed that injuring the muscle in a mouse’s leg puts cells in the other leg in an “alert state” that involves the activation of the mTOR pathway, similar to the body-wide response to amputation that Whited’s lab discovered.

Scientists have similarly found that severed human fingertips can regenerate, but not whole fingers. When regenerative biologist Tatiana Sandoval, a researcher at the Dresden University of Technology, studied patients with fingertip amputations, she observed how seamlessly fingertips regrow—with just a hint of a scar. At that point, her question “changed from why axolotls can do it and humans cannot, to why we can do it in the fingertip but not beyond,” says Sandoval, who was not involved in Whited’s work.

There’s still a lot of biology to unravel before any benefits to humans might emerge, Whited notes. But every new discovery, she says, is a step forward: regrowing human limbs is “a very lofty goal,” but “I do hope that whatever insights we gain from doing this work will be translated into mammals, [including] ultimately humans.”