In the fall of my first year at Harvard Law School, my roommate and I threw a “come as your favorite case or legal doctrine” Halloween party. Our Hastings Hall dorm room was filled with law students dressed as a motley crew of criminals and tortfeasors (and one “fertile octogenarian,” embodying an obscure legal presumption from trust and estates law). Among the partygoers was my roommate, Paul Engelmayer ’83, J.D. ’87, who tied ketchup-covered raw chicken drumsticks around his neck. He had come as Thomas Dudley, an English captain who was put on trial for murder in 1884 because, after a shipwreck, with no food in his lifeboat, he decided that the only way to survive was to kill and eat the cabin boy.

That Halloween party image stayed with me over the years, and it led me to write a book about The Queen v. Dudley and Stephens, the case in which Dudley and his mate were tried for murder. It is fitting that the origins of the book, Captain’s Dinner: A Shipwreck, an Act of Cannibalism, and a Murder Trial That Changed Legal History, lie on the Harvard campus. After all, Dudley and Stephens—one of the most famous cases in Anglo-American law—has long had a strong connection to the University. Many Law School alumni will remember it from first-year criminal law, and Harvard College graduates might know it from “Justice,” one of the College’s most popular courses. The case has been dissected in the Harvard Law Review more than once, by some of America’s leading legal thinkers.

Dudley and Stephens is, as I like to say, Harvard’s favorite cannibalism case. And it’s as relevant today as ever.

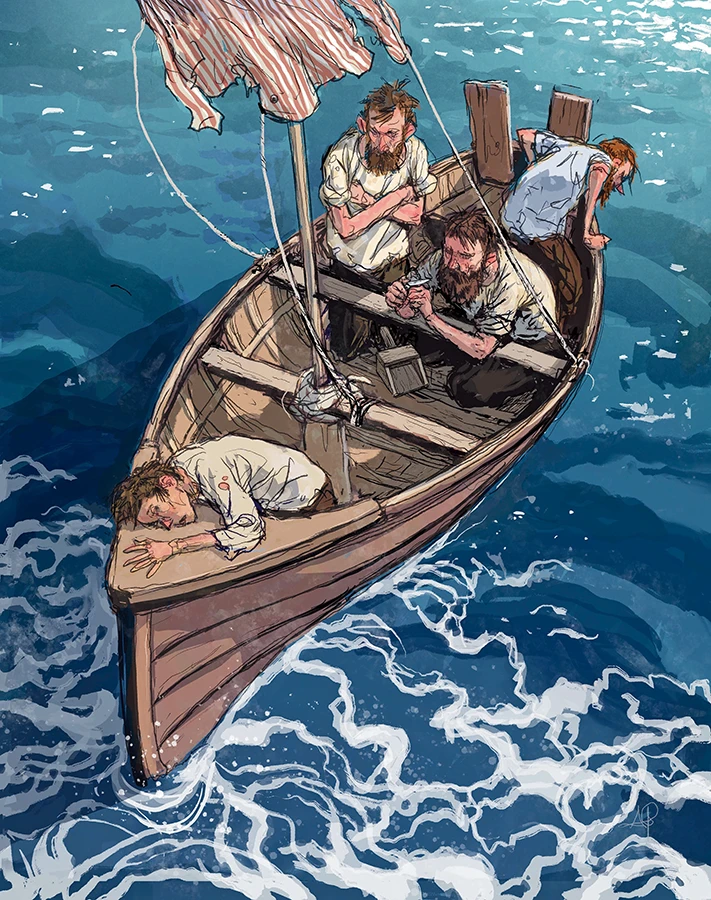

The case began after a wealthy lawyer from Australia purchased a yacht named the Mignonette and hired Captain Dudley, an experienced seaman, to deliver it from England. Dudley set out from Southampton in May 1884 with three crew members. They hit a storm off the coast of Africa. The Mignonette was swamped by a massive wave that towered halfway up its masthead and destroyed the ship. The men barely escaped with their lives, and they did so in a lifeboat with almost no food or water.

They drifted for over three weeks in that tiny boat, during which, among other misadventures, they had to fight off a shark that rammed them from below. When the captain decided they were in danger of dying of hunger and thirst, he slit the neck of the cabin boy, Richard Parker, an amiable 17-year-old orphan who had been excited to make his first real sea voyage. The captain said he chose Parker because the cabin boy was the weakest of the four, having drunk seawater that made him sick—but the truth was, it was almost always the cabin boys, or racial or national minorities, or others at the bottom of social hierarchies, who were chosen to be eaten. The three surviving men feasted on the boy’s body.

To be a bit more specific: they collected his blood in a bailer and drank it (thirst being a more immediate threat than hunger), then tore out his heart and liver and ate them while they were still warm.

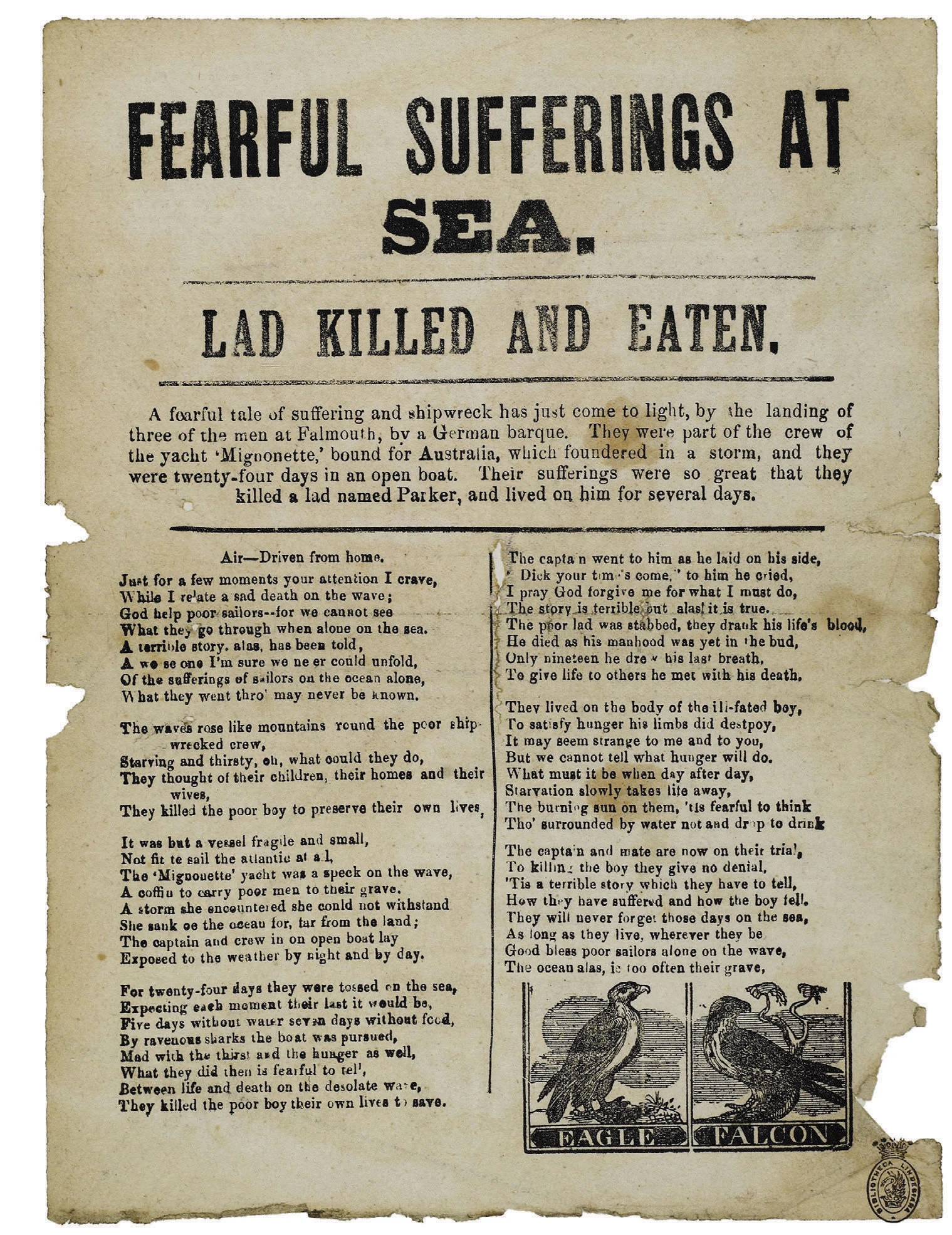

Days later, the men were rescued by a passing ship and brought back to England. They told everyone about their star-crossed voyage, including the part about killing and eating the cabin boy, because they did not see any reason not to. There was, at the time, a long and well-known tradition of sailors who ran out of food killing and eating people to survive, quaintly known as “the custom of the sea.” (It was common enough knowledge that it even made it into popular literature like Lord Byron’s “Don Juan,” which includes an act of survival cannibalism at sea.) The logic behind this was practical: it was better for one person to be killed than for several people to die of starvation.

But in the reform-minded Victorian era, attitudes were changing toward many old practices, including the custom of the sea. Dudley and his mate, Edwin Stephens, were put on trial for murder—the first Englishmen to be charged for cannibalism at sea. The men were found guilty, in a decision written by no lesser authority than the lord chief justice.

Although it is an English case, Dudley and Stephens, after making international headlines, was embraced by American courts, which used it to modify the law of murder. Three years before the Mignonette shipwreck, in 1881, the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., A.B. 1861, LL.B. ’66, LL.D. ’95, wrote in his great treatise The Common Law that “even the deliberate taking of life will not be punished when it is the only way of saving one’s own.” But after the Dudley and Stephens decision, judges in the United States were less willing to allow people charged with murder to invoke the “necessity doctrine,” which excuses some illegal acts if they are done to prevent a greater harm.

By 1931, Benjamin Cardozo, another great Supreme Court justice, wrote that “where two or more are overtaken by a common disaster, there is no right on the part of one to save the lives of some by the killing of another.” Eventually, and maybe inevitably, a case this provocative made its way to college and law school curricula, becoming a staple of first-year criminal law classes across the country.

Much of the world’s knowledge can be fit neatly into various categories, moral and otherwise. Brown v. Board of Education, good. Stalin’s starving of the peasants, bad. Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, great art. Margaret Keane’s paintings of big-eyed children, irredeemable kitsch.

Dudley and Stephens raises one of the greatest moral quandaries of all time: is it acceptable to sacrifice one life to save more lives?

Dudley and Stephens lies tantalizingly in a moral netherworld. Beyond its impact on the law of murder, and its unusual cannibalism storyline, it raises one of the great moral quandaries of all time: is it acceptable to sacrifice one life to save more lives?

Whether, and when, it is acceptable to sacrifice an innocent for the greater good is a question that the Greek philosophers debated—they had a famous hypothetical about two sailors clinging to a plank in the water that could save only one of them from drowning—and that the Bible and other great religious texts wrestle with, in stories such as God’s instruction to Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. Even more appealing for academics is that Dudley and Stephens almost perfectly embodies one of the great divides in modern philosophy, between utilitarianism and rights-based theories of justice. (In this regard, it is a real-world version of the “trolley problem,” another well-known thought experiment in which a conductor can save multiple lives by redirecting an out-of-control trolley to kill one innocent person.)

That’s a major reason why Dudley and Stephens was taken up with enthusiasm at Harvard Law School not long after the case was decided. It was such a favorite with professors and students in the first half of the twentieth century that in 1949, Lon Fuller, one of the most distinguished members of the faculty, wrote an article for Harvard Law Review based on its facts, musing about what justice required.

That article, “The Case of the Speluncean Explorers,” reimagined the case as one of amateur cave explorers in the distant future who, after being trapped in a cave by a landslide, were convicted of murder for killing and eating a member of their group to survive. Their appeal reaches the fictional “Supreme Court of Newgarth” in the year 4,300, and Fuller wrote a set of legal opinions by fictional justices, which, taken together, suggested that no side in the debate had a monopoly on logic or morality.

Fuller’s article became one of the most cited law review articles ever written. In 1999, for the article’s 50th anniversary, Harvard Law Review published a symposium of mock justices’ opinions based on Fuller’s hypothetical, including one written by Cass Sunstein (then at the University of Chicago, now the Walmsley University Professor at Harvard), and with an introduction by the late David Shapiro, a revered Law School professor of civil procedure. Once again, the opinions pointed to the difficulty of resolving the case in any satisfactory way. The mock vote on whether to affirm the defendants’ conviction at trial ended in a 3-3 tie.

The same sharp divisions that existed among the mock justices have been found for many years in Harvard classrooms, as students debate the central question of whether it is ever permissible to kill an innocent person to achieve a greater good.

The logic of the case can be applied to everything from torture to the programming of self-driving cars.

Indeed, the questions Dudley and Stephens raises can feel strikingly relevant to real-world issues today. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a leading medical ethicist in England invoked the case when discussing how doctors should make decisions about allocating ventilators when there were not enough for everyone who needed them. The logic of Dudley and Stephens can be applied to everything from torture (of, say, a captured terrorist, in an effort to obtain life-saving information) to the programming of self-driving cars.

At the College, Dudley and Stephens is best known for the prominent place it has in one of Harvard’s most beloved undergraduate courses, “Justice,” taught by Bass professor of government Michael Sandel. The broad survey of Western philosophy devotes an entire class period to Dudley and Stephens because, Sandel explains, the case almost perfectly illustrates the great philosophical debate between utilitarians, like Jeremy Bentham, and those who espouse a rights-based theory of justice, like Immanuel Kant.

The utilitarians really do have a point: it would be terrible for four people to die if three could live. But then, so do the rights-based thinkers: the murder of an innocent is wrong, and the cabin boy had a right to continue to live his life.

A recorded Justice lecture in a packed Sanders Theatre, available as part of a free-to-audit online course, makes it clear just how differently—and strongly—students feel about the case. “I think the essential element in my mind that makes it a crime is the idea that they decided at some point that their lives were more important than his,” one says of the defendants and the cabin boy. Another student makes a more elemental point: “Cannibalism is, I believe, morally incorrect—so you shouldn’t be eating a human anyway.” Other students see it very differently. “In a situation that desperate,” says one, “you have to do what you have to do to survive.”

Of course, a great thing about the case is how many ways it can be viewed—exactly what works well in a Harvard classroom. According to the custom of the sea, lots are supposed to be drawn to see who is killed, something Dudley did not do before choosing the cabin boy to die. But would it matter if lots had been drawn? Would it be enough to justify the killing that lots were drawn randomly—or is it necessary that everyone at risk of being killed and eaten consent to participating in the drawing? And as for the cannibalism, is that an independent moral wrong? Do we only object to it because there was a killing first, or would it have been wrong to eat the cabin boy if he had died of natural causes? (In other words, independent of the right not to be killed, do we have the right not to be eaten?) There is, forgive me for saying it, a lot to chew on.

Despite the arresting fact pattern of Dudley and Stephens, the moral issues it raises transcend a cannibalism case. That said, it is a cannibalism case. And a less noble explanation for its popularity may be the fascination that people—Harvard people included—have for the macabre. In a first-year law school curriculum heavy with tort cases over standards of negligence and civil procedure disputes over when courts have jurisdiction, Dudley and Stephens offers a more viscerally interesting set of facts: a defendant who calmly takes out his pen knife, slits a boy’s throat, and begins drinking and eating.

At a place like Harvard, one could argue that the fascination goes even deeper. Freud said that cannibalism is one of humanity’s three “instinctual wishes,” along with incest and the lust to kill. He believed that people are drawn to cannibalism because of their innate aggressiveness. Could it be that the story of a man who survives by drinking a coworker’s blood resonates at a school with a deep-seated competitiveness?

Test Your Moral Compass Questionnaire

What should the crew of the Mignonette lifeboat have done in 1884? Join the philosophy discussion that has captivated Harvard students for decades by taking the quiz below. Responses may be published online and in print.

Editor's Note: This survey has closed. You can read the results in the March-April 2026 issue of Harvard Magazine.

Create your own user feedback survey

Pop psychology aside, it’s clear that people like to talk about cannibalism. It is embedded in a shocking number of the most famous fairy tales, like “Hansel and Gretel,” in which the witch builds her gingerbread house to attract children to eat. It is a fixture of modern pop culture, from Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs, to the stranded girls’ soccer team in Yellowjackets, to Alive, the true story of the Uruguayan rugby team that resorted to cannibalism after a plane crash—not to mention all of those Jeffrey Dahmer movies and TV series. I can vouch, as someone who has spent the last few years writing a book about cannibalism, that people have a lot of questions. Including, yes, what it tastes like. (In case anyone asks: not chicken, but pork.)

One thing people who have encountered the case in college or law school would likely agree on is that Dudley and Stephens sticks with you. I didn’t study the case in law school—incredibly, my criminal law professor had other priorities—so my only exposure to it was at that Halloween party, through what I learned about it that night. But it made a deep enough impression on me that years later, when I was looking for a topic for my next book (and wanted a change of pace from the one I had just written, a serious look at the last 50 years of Supreme Court rulings), I was drawn to the events in the Mignonette lifeboat.

My law school roommate and good friend Paul Engelmayer—who dressed up as Captain Dudley that Halloween and who is now a federal judge in New York—agrees. “It’s memorable how electric it was,” he recalls. Engelmayer studied the case with Richard Parker, a Harvard Law School professor who, in one of the odder Harvard connections to the case, shares a name with the cabin boy. The class discussions, Engelmayer says, made everyone think about what they would have done under the circumstances.

“This case is a clash of absolutes—the desire to save as many lives as possible pitted against the desire to avoid taking an innocent life,” he says. “And there is just no easy way out of it. Harvard loves problems like that.”