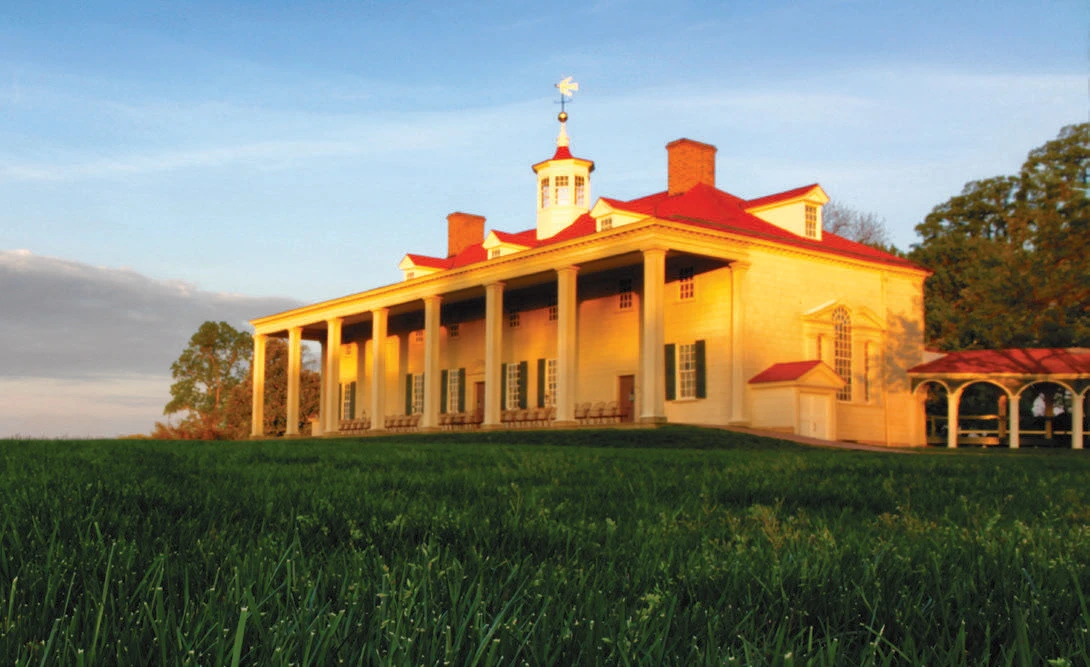

Set on a hill above the Potomac River, George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate roots Americans in an essential shared history.

There’s his house, fully reopened after a $40 million renovation. There’s a working farm highlighting his composting “dung repository” and other scientific innovations. Other museum exhibits explore his prescient views on overzealous partisanship and religious freedom. “More than any of the other founders, Washington probably still suffers from the ‘marble statue syndrome’—distant and unapproachable,” says Anne “Dede” Neal Petri ’77, J.D. ’80, regent of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA), which owns the property. “But he was a living, breathing, fascinating human being.”

Along with others at the estate, Petri has been helping to prepare for this year’s 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. That includes George Washington: A Revolutionary Life, a new exhibit opening in March that looks at his character and beliefs partly through his behind-the-scenes work at the 1787 Constitutional Convention and the evolution of his thinking about slavery. Ultimately, he freed his slaves upon his death, as reflected in his will (which will also be on display).

The three-year mansion revitalization effort mainly addressed critical infrastructure problems, but it also refreshed Washington’s bedchamber. And in October, visitors will, for the first time, be able to venture into the cellar, where archaeologists have unearthed “35 bottles of miraculously preserved” fruits and berries dating to 1775, the year Washington went off to war. “He had no idea that he wouldn’t return until 1783,” Petri says. The preserves were stored in the cellar and forgotten. When uncovered in 2024, almost 250 years later, “one bottle was opened and you still had a whiff of fresh cherries,” she says, with a smile. “Now that’s really historic preservation.”

Elsewhere, Mount Vernon reflects the country’s history of slavery. In 1929, the estate’s stewards installed a stone marker on the burial ground of enslaved people (now a site of continuing research), and in 1950 they reconstructed slave quarters that had burned down. Those areas, along with the 1983 Slave Memorial and a new 2025 exhibit called Lives Bound Together, help tell the layered stories of people enslaved at Mount Vernon. Historic preservation today, Petri says, prioritizes “providing visitors a rich picture of our complex past. We believe that the full story—joyous and painful—is part of Washington’s legacy.”

For Petri, who concentrated in American history and literature at Harvard before attending Harvard Law School, historic preservation is linked to a strong perspective on education. A onetime general counsel for the National Endowment for the Humanities under then-chairperson Lynne Cheney, she joined Cheney, Saul Bellow, U.S. Senator Joseph Lieberman, and others in 1995 to co-found the National Alumni Forum, now known as the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA). The nonprofit organization, according to its mission statement, “is dedicated to promoting academic excellence, academic freedom, and accountability at America’s colleges and universities.”

Petri served as the group’s president from 2003 to 2016, leading initiatives and writing many pieces on core curricula and historical literacy. Prior to that she co-authored ACTA’s 2000 report “Losing America’s Memory: Historical Illiteracy in the 21st Century,” which warned that “future leaders are graduating with an alarming ignorance of their heritage—a kind of collective amnesia—and a profound historical illiteracy that bodes ill for the future of the republic.” (In 2023, well after Petri’s departure from operational activities at ACTA, the organization was listed on the advisory board of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 policy initiative—although in November 2025 ACTA issued a statement that it had disengaged from the Heritage Foundation.)

The American Association of University Professors, a national organization representing some college faculty members, researchers, and graduate students, criticized ACTA in a report last February, writing that the group was mobilizing university trustees “to disrupt the entire higher education sector and rebuild it to conform to the interests of corporate-dominated boards and the political right.” Asked to respond, Petri noted that “Board members have a fiduciary duty to their institutions. Many institutions are now faced with unconscionable federal intervention because trustees have remained quiet.”

Speaking to a reporter during a tour of Mount Vernon last spring, Petri discussed the importance of higher education and suggested that a changed approach to teaching history could help the U.S. overcome its current lack of national unity. “We’re a deeply fractured people right now, and our schools and colleges and universities are not helping,” she said. “Engaging students with our history—the good and the bad, the tragic and the uplifting—can serve as a common denominator.”

It ultimately comes down to what Washington, LL.D. 1776, himself understood, she later wrote in an email, citing parts of his first annual address to Congress in 1790: “Knowledge is in every country the surest basis of public happiness. Every valuable end of Government is answered by…teaching the people themselves to know and to value their own rights; to discern and provide against invasions of them; to distinguish between oppression and the necessary exercise of lawful authority.”

Petri’s own trust in that cause is partly rooted in family history. Her father, James T. Neal, was a third-generation owner and editor of The Noblesville Daily Ledger, a newspaper in Indiana. She remembers as a girl when a sheriff arrested her father for contempt of court because he’d written a column criticizing a county judge’s policy of treating traffic offenders as serious criminals. The case went on for three years and was ultimately dismissed. “So I was sort of born of this crucible,” she says, “of my father,” despite freedom of the press, “being challenged.”

At Harvard she worked at the Crimson (as did her mother, Georgianne Davis ’51); after law school, she practiced First Amendment law with Rogers & Wells in New York City and then served as deputy general counsel of the Recording Industry Association during its campaign to oppose mandatory lyrics labeling. By 1982 she had landed in Washington, D.C., as general counsel at the Office of Administration under President Ronald Reagan. Her life in politics deepened the following year when she married Thomas Evert Petri ’62, LL.B. ’65, the U.S. representative for Wisconsin’s 6th congressional district from 1979 to 2015. (Their daughter, Alexandra Petri ’10, is a staff writer at The Atlantic.)

Over the decades, Petri has also lent her expertise to cultural organizations focused on historic preservation and landscapes. She served as president of The Garden Club of America, then became CEO and president of the Olmsted Network, where she led the nationwide bicentennial celebration of Frederick Law Olmsted, A.M. 1864, LL.D. ’93, a key figure in the development of American landscape architecture. Her fascination with Olmsted stems from an earlier role in restoring woodlands by the Washington National Cathedral. “There are just some things that history books can’t do,” she says, “and that’s why historic preservation, and what we do at Mount Vernon, is so important. It’s about the power of place.”

Her elected three-year voluntary role at Mount Vernon marries her interests in historic literacy and preservation. The property resonates with the voices of visitors, even though she’s found that “many people who come here know very little about George Washington.” That would have seriously alarmed Anna Pamela Cunningham, who founded the MVLA in 1853. Cunningham, the daughter of South Carolina cotton plantation owners, rallied supporters to raise $200,000 to buy the deteriorating mansion and surrounding 200 acres of land. (Edward Everett, a Washington advocate and the former Harvard president, raised about a third of that total.) Petri admires Cunningham and the other original “ladies” of the MVLA “who couldn’t vote and had no right to own property, and who decided that this was a goal worth pursuing and that they were going to do it by themselves.” The concept of people volunteering to work together to “do things that will improve our society, that don’t require government involvement, I found that very powerful,” she says. “And throughout my life I have really tried to be an engaged citizen.”

Petri is attuned to Mount Vernon’s potential power as a unifying force—and knows that today’s tinder-box politics would not have been unfamiliar to Washington. During tours or speeches, she often references Washington’s 1796 farewell address to the nation following his decision to retire from public life. In it, he identifies three major threats: foreign influence, regionalism, and partisanship. “He’s the only president who was not a member of a political party,” Petri notes, “not that there was something wrong with those, but he did not want those things that divide us to take supremacy over what unites us. He was already anticipating what could happen. He worried that an overweening partisanship could be a threat to a well-functioning republic.”

At Mount Vernon, Petri wants visitors to immerse themselves: to meander in Washington’s home, to view the Potomac from his porch, to see the bed where he died and the study where he began each workday at 4 a.m. “We want people to understand that a young surveyor who grew up on a farm with a single mother could go on to defeat the mightiest armed force on earth,” she adds, and to leave Mount Vernon “feeling something in their hearts for a man willing to pledge his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor to the cause of liberty.”