“There it is,” says Catherine Zipf ’94, striding down a narrow residential street in Providence, Rhode Island, and pointing toward a house near the top of the hill. Built in the early 1800s, it’s big and boxy, with blue clapboard walls, a bright red brick foundation, and a bay window jutting out over the sidewalk. “Fifty-eight Meeting Street,” Zipf says, reciting the address from a printout she’s brought. The building isn’t extraordinarily significant as a piece of architecture (though it’s still “cute as the dickens,” she says with a grin), but as a piece of history, it is. In the 1930s and 1940s, this was the Mrs. M.A. Green Tourist Home, one of 24 Rhode Island businesses listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book.

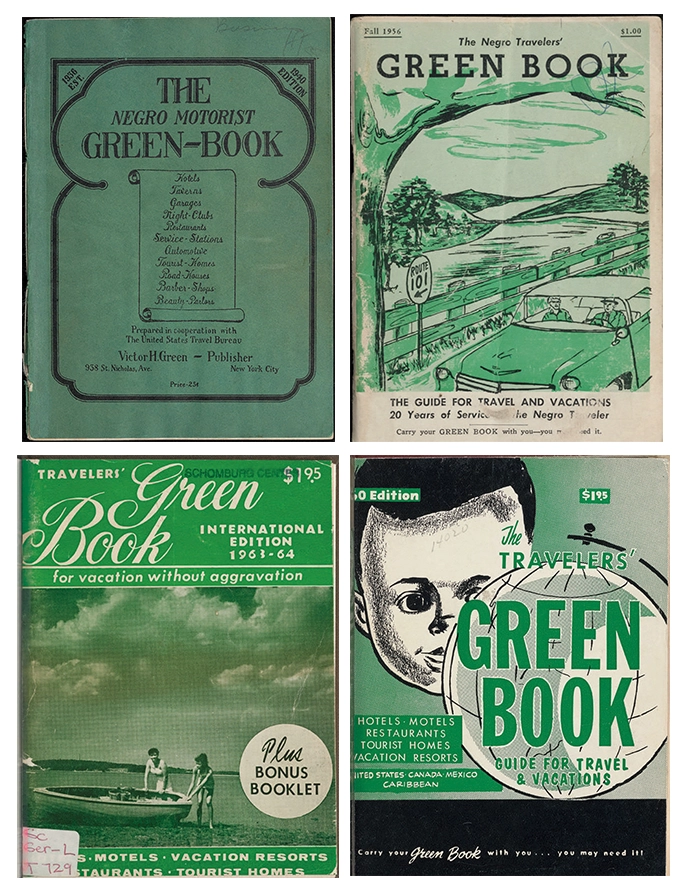

Zipf knows all 24. An architectural historian who leads the historical society in the nearby picturesque coastal town of Bristol, she is part of a research team that has been working since 2016 to compile a database of every business ever listed in the Green Book, the Jim Crow-era guide that helped Black travelers find safe lodging, restaurants, and other services. Founded in 1936 by Victor Hugo Green, an African American postal worker in New York City (who died 65 years ago this October), the Green Book was updated annually until 1966. In those three decades, more than 15,000 businesses appeared in the book’s pages: flower shops, beauty parlors, gas stations, parks, beaches, dance halls, with some listed only once and others showing up year after year.

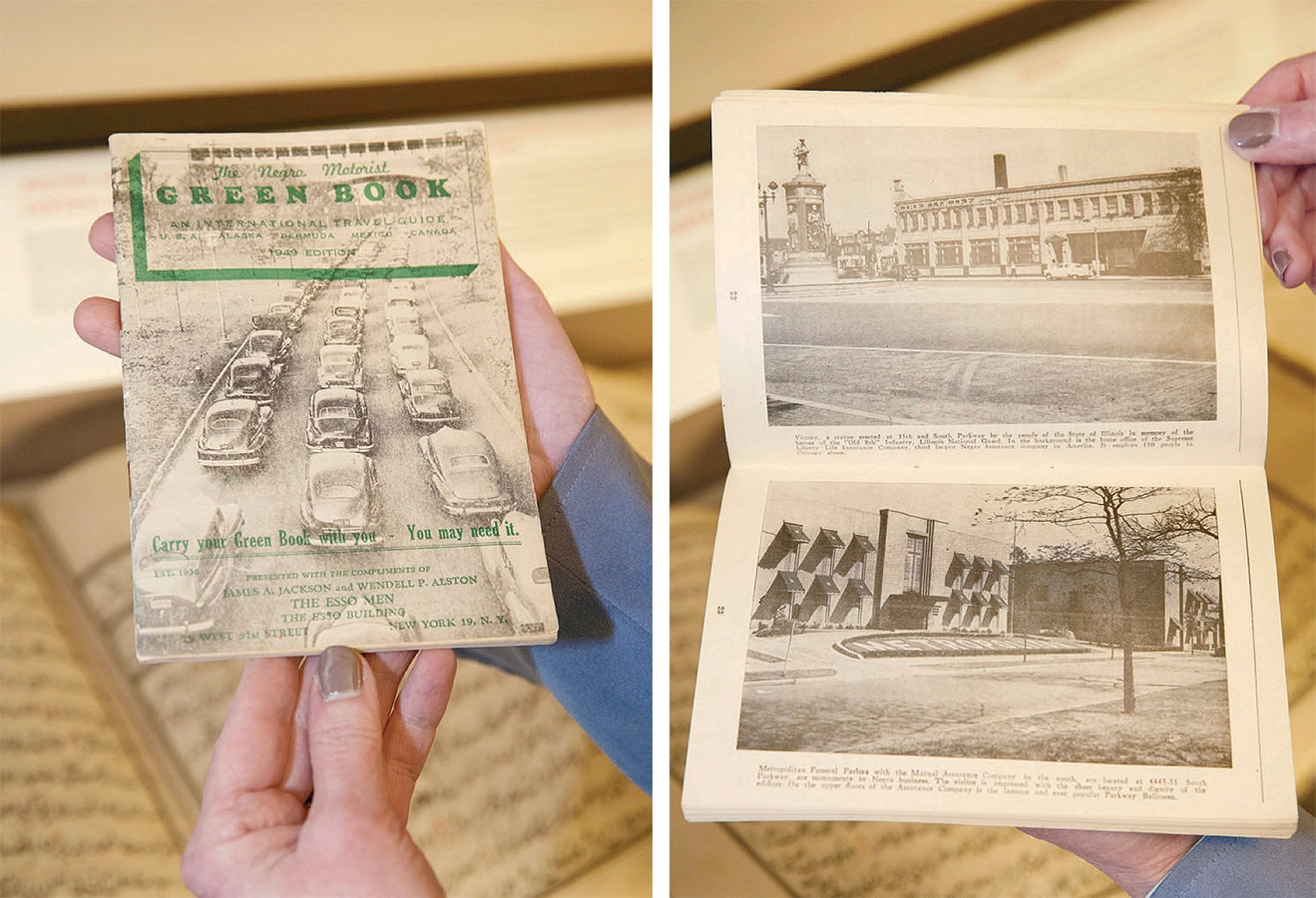

Until recently, though, the Green Book had largely slipped from public memory. “The story goes that the Civil Rights Act was passed [in 1964],” Zipf says, “and then everybody tossed their Green Books.” But about 10 years ago, the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture digitized its entire collection. For Zipf, this was a revelation. Back then, she wrote a monthly architecture column for The Providence Journal and chronicled some of the Green Book’s Rhode Island listings, including the Mrs. M.A. Green Tourist Home. “There is a lot more that could be known about these buildings,” she wrote. “I’d love to see maps and maybe even a tour of surviving sites.”

Anne Bruder, a fellow architectural historian and Zipf’s graduate school roommate at the University of Virginia, got in touch after reading the column to propose they do exactly that. The pair recruited another graduate school classmate, Susan Hellman, and their research project soon snowballed into a full-fledged effort to build a database, which they called “The Architecture of the Negro Travelers’ Green Book.”

“This is very fragile history,” Zipf says. She means this literally—many of the Green Book buildings are demolished or in disrepair, and few have been formally preserved—but her statement is also true in another sense. Often, the only way to know if a particular site was in the Green Book is to look for it…in the Green Book. That’s because listings there were rarely recorded in other archival sources. This is the case even for buildings with substantial documentation. Zipf, a former history professor at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, remembers leading a student through a research project on a restored home in Newport, only to find out years later that it had once been a Green Book tourist home.

“We spent an entire semester on that house, and none of the records turned up that fact,” Zipf says. This lacuna, she believes, “creates an urgency to put that history more prominently out there.”

The database is only one of a half-dozen projects that Zipf has spinning at any given time, but it’s part of an interest that has threaded through her career—and, really, her whole life. Growing up in Scarsdale, New York, she was interested not just in buildings, but also the people in them. “My dad would take me to tag sales,” she says, “and I would run around the houses, figuring out how they were put together, and how people lived in them.”

At first, she thought this meant she should be an architect. At Harvard, she declared a special concentration called “design science” that consisted, essentially, of courses in the visual and environmental studies department (now art, film, and visual studies), plus a little mathematics and engineering thrown in. Then, while applying to architecture graduate programs as a senior, she stumbled across the University of Virginia’s program in architectural history. “It was love at first sight,” she says. The day the acceptance letter arrived, “I bounced my way up all four flights in Winthrop House.”

Her Ph.D. thesis (later a book, Professional Pursuits) looked at the Victorian-era Arts and Crafts Movement and how its association with domestic spaces allowed women to sidestep barriers that usually kept them out of professional life, to become business owners, editors, designers, and architects. In other writing, she’s examined “the gendered politics of public space”; a Modernist female architect named Chloethiel Woodard Smith; and Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Fallingwater. Zipf spent nine years on the faculty of Salve Regina and four years as a research scholar at MIT before joining the Bristol Historical and Preservation Society in 2016 as executive director.

That job turned out to be a perfect fit. The society is one of dozens of similar organizations dotting New England, and its headquarters is the former town jail, an 1828 granite building with more than enough eccentricities to keep an architectural historian occupied. Part museum and part office, it includes a restored two-story cell block with metal cots that fold up against the wall and rooms upstairs where the jailkeeper lived with his family. (Also upstairs: a “VIP” cell with its own fireplace, as well as three airless “dungeon cells,” which Zipf says might have been used to hold people with mental illnesses. “In the nineteenth century, you’d go to jail for that,” she says, then adds, after a pause, “We like to think that the dungeon cells were empty most of the time.”)

The building sits near Bristol’s main thoroughfare, and locals, tourists, and school groups waft in and out all day. About once a week, there’s a visit from the “ghost guy,” a retired firefighter who conducts paranormal investigations. He approached Zipf a few years ago, asking if he could do some research in the jail. She said OK. “I feel very strongly that the historical society should be a resource to the community, of service to the community,” she says. “So, unless the asks are just really burdensome, I generally say yes.”

Bristol itself, a colonial-era town with a deep-water port that was once one of the country’s most significant, offers plenty for an architectural historian. Walking down Hope Street, with its stone churches, brick storefronts, and gabled roofs, Zipf says, “I can’t unsee the layers.” The original wooden planks behind artificial siding, the old proportions clinging to replacement windows, the way a chimney’s shape reveals its age, no matter what the rest of the building seems to insist—sometimes it can be overwhelming. “It’s like fanning through a pack of cards,” she says.

The life stories inside the architecture have a similar effect. Bristol’s history is intertwined with that of the infamous DeWolfs, a family of slave traders and privateers who owned sugar plantations in Cuba and mansions in New England. Their fortunes funded the town for generations—and built many of its buildings, including banks, warehouses, and a rum distillery. Standing in front of Linden Place, a stately mansion erected in 1810 by George DeWolf, a ne’er-do-well nephew of the family patriarch, Zipf explains how he ended up fleeing the country in the middle of the night after a series of disasters tanked his businesses abroad and his creditors came calling. The home he left behind, now a museum, is an impressive sight—a Federal-style colossus, all white, with grand Palladian windows, soaring Corinthian columns, and a roofline balustrade. It was built, she says, from the proceeds of a single slave voyage. Among her research projects is an exploration of Bristol’s enslaved residents.

The Green Book project, meanwhile, continues apace. So far, Zipf and the others (including a host of volunteers based throughout the country) have compiled data on sites in 20 states, plus Washington, D.C. For each entry, they document property histories, verify names and addresses, look up census data, and check to see whether the buildings still exist. Whenever possible, they visit the site and snap a photo. In Custer, South Dakota, Rocket Court (now the Rocket Motel) is still in operation next to U.S. Highway 16, its giant red neon sign lighting up the roadside. In Amarillo, Texas, a man named Gabriel B. Carthen ran the Blue Moon Billiard Hall, now demolished. In northwest Baltimore, owner John Whirley hosted live music at the Ubangi nightclub. That building still stands, though it’s seen better days. The ground floor is mostly bricked up, and the two stories above it are covered in Formstone, a type of fake-stone stucco characteristic of Baltimore rowhouses. Hosted on the University of Virginia’s website, the database is searchable by year, state, establishment type, and owner.

Zipf did the research for Rhode Island’s Green Book sites, all but one of which are clustered in Newport and Providence. The Mrs. M.A. Green Tourist Home, listed in the book from 1939 to 1948, was run, she explains, by an African American widow named Martha A. Greene; she lived there with her daughter (also Martha), who worked as a maid, and a lodger named William P.H. Freeman, who sold real estate. Two doors further up stands the Hill Top Inn, another tourist home, while at the bottom of the street is a parking lot where the Bertha Hotel once stood. A few blocks away are a handful of other sites: beauty parlors, a restaurant, more tourist homes. Most of the buildings that remain are within the College Hill Historic District, established in 1960. The preservation effort wasn’t aimed at the Green Book, though—it was meant to save homes in the oldest part of the city. In fact, the designation sparked a wave of gentrification that pushed out African American residents. (Through the 1950s, this was a Black neighborhood.)

There’s a lot of American history wrapped up in ironies like that, Zipf says, including the fragility of African American stories and sites. She walks to the edge of the historic district, where residential Benefit Street converges with the busy Main Street. To her right stands the former Lucille’s Beauty Parlor, a cream-colored building with stairs up the side. Across the street, just steps outside the historic district, were Dinah’s Tourist Home and Restaurant and Hines Tourist Home. The building was demolished in 1963. Zipf looks down again at her printout, which includes a map of the neighborhood from 1937, filled with buildings that no longer exist. She looks up again at the modern-day neighborhood all around her. She can’t unsee the layers.