Among the items on display in the exhibit titled Prescriptions for Peace is the book Surviving Nuclear War. It offers instructions for creating a DIY face covering to protect yourself from radiation, along with advice on how to dig a ditch and line your clothes with newspapers to stay warm. The underlying message of false assurance is just the kind of soft-pedaled, propagandistic misinformation that motivated the physician-led movement against nuclear war between 1961 and 1985. The exhibit highlights pioneering activists, including Harvard-affiliated leaders, and a movement that proved to be an effective model for activism still relevant today. “Right now, there are more than 13,000 nuclear weapons at large in the world,” says exhibit co-curator Katie Blanton ’18, M.D. ’25. “Nine countries have access to them, and 22 countries have materials that could be used to build a nuclear bomb. That’s all to say that, in 2025, the anti-nuclear movement is as vital as ever.”

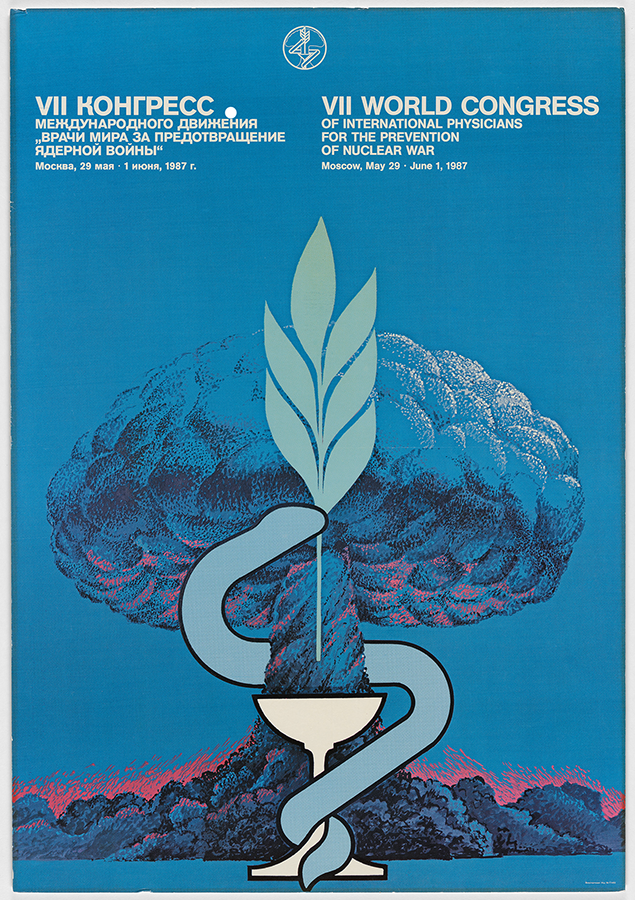

The exhibit focuses particularly on Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR), an organization founded in 1961 to educate the American public on the health consequences of the testing and potential deployment of nuclear weapons, and the group it later spawned, the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW). Posters, buttons, newspaper clippings, photographs, and letters are on display, along with examples of activists’ efforts to contradict prevailing ideas about surviving a nuclear attack. Excerpts from 10 films are screened, including “interviews with 1980s Boston-area children discussing their fears and reactions to nuclear war,” notes co-curator Heather Mumford, an archivist at the T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

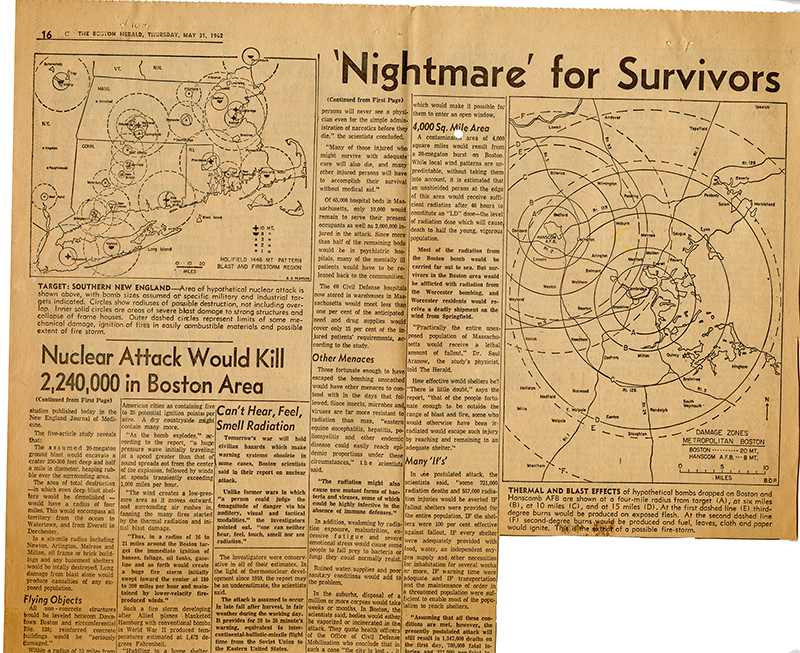

Perhaps most vivid and influential in the anti-nuclear campaign, she says, were maps showing the hypothetical devastation from a nuclear bombing of Boston and New York City. These marked the first time such scenarios were spelled out to Americans, based on medical and scientific research conducted by PSR and IPPNW. The exhibit highlights Harvard-specific activism, such as a syllabus for the Harvard Medical School course “Health Aspects of Nuclear Warfare” and a flier for a protest at the Harvard School of Public Health. Also on display are early records relating to the groups’ activities that were drawn from the collections of several PSR- and IPPNW-affiliated Harvard faculty members. (They include, from Harvard Medical School: Herb Abrams, Cook professor and chairman of radiology emeritus; James E. Muller, senior lecturer on medicine; Lachlan Forrow, M.D. ’83, lecturer on global health and social medicine; and Alexander Leaf, former Jackson professor of clinical medicine and later Watts professor of preventive medicine. Other PSR- and IPPNW-affiliates include: Eric Chivian ’64, M.D. ’68, associate of the department of organismic and evolutionary biology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; Bernard Lown, T.H. Chan School of Public Health professor of cardiology emeritus; Jennifer Leaning ’67, S.M. ’70, current senior research fellow at the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights and retired professor of the practice at T.H. Chan School of Public Health and HMS faculty member; and Victor Sidel, M.D. ’57, former distinguished university professor of social medicine at Montefiore Medical Center (MMC) and Albert Einstein College of Medicine and chair of the Institutional Review Board for Protection of Human Subjects in Research at MMC from 1973 to 2005.)

Of the documents, Mumford notes the written correspondence from 1979 between the prominent Soviet cardiologist Yevgeniy Chazov and pioneering American cardiologist Bernard Lown (a co-founder of PSR and IPPNW, and founder of the Lown Institute). The two men are part of a group of Harvard and Russian physicians who co-founded IPPNW in 1980 (along with Muller, Chivian, and Abrams, of the United States, and Mikhail Kuzin and Leonid Ilyin, of the Soviet Union). In one letter, Chazov expresses a “shared commitment for Russian and U.S. doctors to form a collaboration between physicians to stop nuclear war.” Years later, in 1985, with the Cold War in its final years and amid the rise to power of Mikhail Gorbachev, the IPPNW won the Nobel Peace Prize.

In all, the exhibit represents some 50 different primary source materials, most from University archival collections, curated by Mumford. The texts draw heavily from Blanton’s senior thesis, “The Doomsday Doctors: Medical Activism in the Nuclear Age, 1960-2000” (which won the 2018 Thomas Temple Hoopes Prize). In talking about the exhibit today, Blanton emphasizes that both PSR and IPPNW are still active in fighting the proliferation of nuclear weapons and potential war. “Countries with and without nuclear weapons must be accountable in preventing both all-out nuclear catastrophe,” she says, “and what the doctors termed ‘the slow poisoning of our world’ from nuclear weapons testing and production.”

These activist organizations enabled medical doctors to apply their expertise to effect change, extending their roles as protectors of public health and safety. “For them, social activism was not an extra-professional activity, but a core part of their identity as physicians,” Blanton adds. “I hope people who see the exhibit will appreciate that activism is well within the doctor’s lane. The advocacy efforts we see today are extensions of a decades-old precedent of physicians crossing into the political sphere to urge us to protect each other.”