The prominent nineteenth-century Quaker abolitionist and writer John Greenleaf Whittier was once in the backyard of his home in Amesbury, Massachusetts, when a bullet flew in and grazed his cheek. Two neighbor boys were target-practicing and had not known, Whittier surmised, that he was walking about on the other side of the fence. Instead of confronting them, however, Whittier simply held a handkerchief to the bloody wound and walked to the doctor’s office.

Such a practical, peaceful response is hard to imagine today. Yet for Whittier, it made natural sense. “He had humility and kindness. He was not the sort of person who would have made a fuss over something he knew was an accident and had no interest in getting the boys in trouble,” says Chris Bryant, board member and former president of Amesbury’s John Greenleaf Whittier Home and Museum. Later, after the boys learned what they had done, one of them painted a picture of Whittier’s beloved birthplace in nearby Haverhill and gave it to him with an apology.

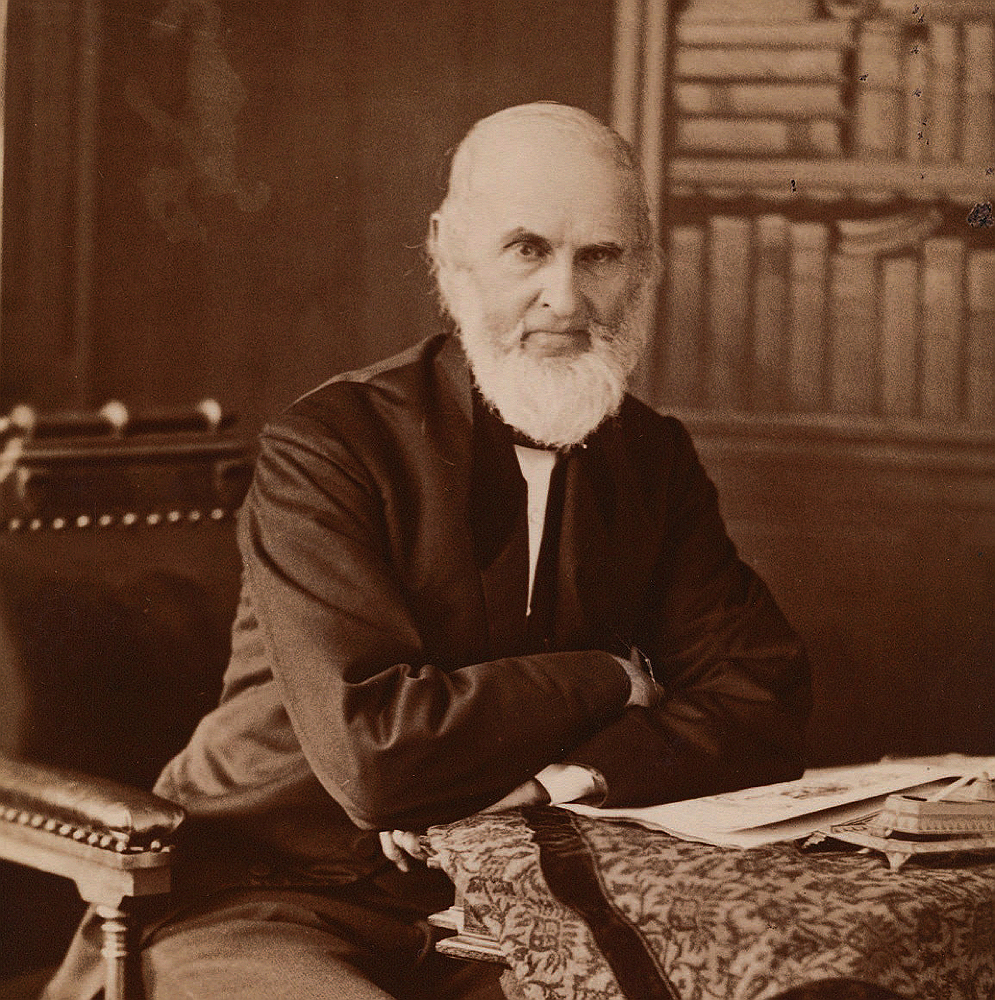

Visitors hear that story—and much more about the multi-faceted poet—during tours of both the Amesbury and Haverhill house museums, which are open to the public from May through October (and check the websites for special events). From his birth in 1807 and publication of his early poems, to his activism before and during the Civil War, Whittier was among the country’s most dedicated and effective opponents of slavery. After the war, he returned to primarily writing poems about the natural world, religion, rural life, and New England. His most famous work, the 1866 Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl, was a salve for a country torn apart by war. He was a revered poetic voice of a changing America and one of the treasured “fireside poets,” alongside his friends Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, LL.D. ’1859, and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., A.B. 1829, M.D. 1836.

In his early days, “he was considered second only to [the staunch social reformer and journalist] William Lloyd Garrison as a leader of the American abolitionist movement,” says Kaleigh Paré Shaughnessy, ALM ’14, executive director of the Whittier Birthplace. “Garrison is still well-known, but Whittier seems to have been forgotten in many ways.” Yet, as a scholar of his life and work, and a Haverhill native herself, she finds his story compelling—and timely. “He’s a great example of what it looks like to care about other people,” she says, “and of fighting for causes that maybe don’t affect you directly as an individual.” These two humble museums speak to a crucial era in American history, a time of divisiveness and violence, of political upheaval and uncertainty. Visitors thus might find it useful to understand more about one man’s non-violent, practical—and impassioned—response to a time not entirely unlike our own.

Whittier arose from modest beginnings on a lonesome farmstead in Haverhill. What’s now the Whittier Birthplace (the setting for Snow-Bound) was originally a four-room house built in 1688 by Whittier’s great, great grandfather. Today, the home and grounds—a bucolic setting with short walking trails—are substantially the same as they were during Whittier’s childhood. He and three siblings, including his most beloved sister, Elizabeth (also an abolitionist), shared the space with their parents, an aunt and uncle, and a series of visitors and hired hands for the farm. “It was a very full house,” says Shaughnessy. “No room was used just for sleeping.” Inside the rough-hewn home, visitors sense the close quarters: a reproduction Murphy-style bed folds down in the parlor and one added bedroom was oddly placed up a few stairs off the kitchen because the family had to build around a boulder lodged in the ground. The original hearth is intact, with cooking tools on display. So are boots that belonged to Whittier, who stood six-foot-three-inches—especially tall for that era. Two of his hats sit on a dresser, along with a top hat, because he was known to prefer those over the traditional wide-brimmed “wideawake” hats donned by Quakers.

The farm, however, was barely profitable. He and his siblings worked hard there and went to school for 12 weeks in the dead of winter, Shaughnessy says. His parents took weekly trips to worship at the Society of Friends meetinghouse nine miles away in Amesbury, and on those rest days, Whittier enjoyed “wandering in the woods, or climbing Job’s Hill, which rose abruptly from the brook which rippled down at the foot of our garden,” he later wrote in a pamphlet-length autobiography.

This natural beauty still abounds. Visitors can take the self-guided Donald C. Freeman Trail, offering signs inscribed with his verses. His own close attention to the natural world and feeling of serenity within it stayed with him for life. But he was not cut out for farming, Shaughnessy notes. Tending toward ill health, he wrote that he’d “inherited from both my parents a sensitive, nervous temperament.” The Whittier home did contain a Bible and a stack of journals from Quaker ministers, and he early on discovered a love of reading and words, such that when he “heard of a book of biography or travel…[he] walked miles to borrow it.”

Tours of the Haverhill museum also reveal that Whittier was 14 when his schoolmaster introduced him to a book of poems by the Romantic writer Robert Burns. That book—which was also with Whittier when he died in 1892 at the home of friends in New Hampshire—now sits on a parlor shelf at the birthplace not far from the desk he used, writing by a window using natural light. Hearing Burns’s poems for the first time, Whittier later recalled, “I begged him to leave the book with me and set myself at once to the task of mastering the glossary of Scottish dialect at its close.” That spurred his own creation of rhyming verses and stories, and led to what he later characterized as a “dual life...in a world of fancy, as well as in the world of plain matter-of-fact about me.”

Five years later, in 1826, Shaughnessy tells visitors, Whittier’s older sister Mary sent one of his poems to the Newburyport Free Press, whose young editor, William Lloyd Garrison, published it, along with subsequent others. Garrison visited, urging the young poet to develop his literary gift. Perhaps seeing education and writing as an escape route from subsistence farming, Shaughnessy says, Whittier earned money to attend a new local school.

By the late 1820s, based on his Quaker principles, Whittier strongly opposed slavery. Influenced and helped by Garrison, he worked on abolitionist and other newspapers in Boston and Hartford, and published a book of prose, Legends of New England—all of which launched his writing career. “He’d found his calling, if you will, in the abolitionist movement,” says Chris Bryant, of the Amesbury museum. “At the time, almost all of his writing—his poetry and articles, essays—were always against slavery.” The American abolitionist movement, spanning from about 1830 through 1870, was gaining ground, but the issue of slavery was obviously politicized and divisive.

Whittier joined the anti-slavery party in 1833 and served as a delegate to the inaugural meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Convention, where 60 leaders from 19 states gathered in Philadelphia and adopted a declaration to fight for emancipation drafted by Garrison. That year, Whittier also published the persuasive tract, “Justice and Expediency,” concluding that “…when under one common sun of political liberty the slave-holding portions of our republic shall no longer sit, like the Egyptians of old, themselves mantled in thick darkness, while all around them is glowing with the blessed light of freedom and equality, then, and not till then, shall it go well for America!” Striving to enter politics, he was elected to the state convention of the National Republican party and failed to win office as a Whig, but in 1835 became a Massachusetts state legislator.

Yet abolitionists faced criticism, ostracism, and violence. In 1835, Whittier was present for several gatherings and speeches when pro-slavery mob rioting broke out, Shaughnessy tells visitors. In Boston, he witnessed Garrison dragged through the streets by a rope tied to his waist (until the police rescued him). Three years later, Whittier was caught inside Pennsylvania Hall, the short-lived hub of abolitionism, when it was torched by a pro-slavery throng. He survived, Chris Bryant of Amesbury says during tours, only by racing around in a hastily assembled disguise, yelling “Hang Whittier! Hang Whittier!”

After Whittier’s father died in 1830, the family sold the farmstead and moved to the Amesbury home to be closer to the Society of Friends’ Meeting House, which was down the street. “Amesbury had a reputation as a liberal, tolerant, and classless society,” and its scenic charm appealed to Whittier, who “was always very sensitive to natural beauty,” Bryant says. “There was hardly a spot from which he couldn’t see a hill, pond, lake, or river.” The town offered closer contact with people and community, although Whittier never married, nor did he appear to have any love interests beyond a girl referenced in his poem “School Days.” He was devoted to his family, especially his mother and sister Elizabeth. The latter also wrote poetry and cofounded the Female Anti-Slavery Society in Boston in 1833, Bryant explains: She was his closest companion, read and commented on his work, shared his love of nature, and had a sunnier social temperament.

Even as he continued to write, speak out, and attend meetings supporting abolition, he stayed in Massachusetts as of 1840, the Amesbury home his anchor for 56 years. The oldest part of the house opened to the public in 1898 and remains virtually unchanged. Four rooms contain original Whittier family furnishings; tours cover them all, along with artifacts. Bryant highlights a framed engraving of Abraham Lincoln in the dining room, telling visitors, “When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, it was a war to save the union. It did not become a war to free the slaves until Jan. 1, 1863. Lincoln told a war correspondent that Whittier’s ‘Luther’s Hymn’ had influenced him to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and that it was the kind of song he wanted all the soldiers to hear.” She recites an excerpt:

O North and South,

Its victims both,

Can you not cry,

“Let Slavery die!”

And union find in freedom?

In Whittier’s bedroom, there is a picture of the Great Elm on Boston Common, which came down in an 1876 storm, and a table he crafted from salvaged tree wood gifted by the Boston mayor. Also hanging around the home are portraits of the Whittier family and his anti-slavery colleagues, among them Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, A.B. 1830, LL.B. 1834, LL.D. 1859. In 1856, he was famously beaten unconscious with a cane by a Southern Congressman in the Senate chamber days after delivering an anti-slavery speech and took years to recover. When Sumner was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, four men surrounded the coffin: Whittier, Longfellow, Holmes, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, A.B. 1821, LL.D. 1866.

The “Garden Room,” Whittier’s favorite place, still holds the small desk where he wrote Snow-Bound beside a wood stove and a bookcase. The original carpet and wallpaper are intact, as are chairs and a sofa, and pictures hung from moldings. His hat is there, too, along with a walking stick made from wood taken from Pennsylvania Hall. A death mask and a cast of his writing hand sit by the front door, and in the parlor is a replica of Charlie the parrot. Whittier took care of the bird after his sister Mary died, giving it free rein of the house and outdoors, where it often swooped to the roof, uttering obscenities to passersby.

The Civil War was a complicated turning point for Whittier. Quaker pacifism leads him to oppose it, notes Shaughnessy, but ultimately, he thinks that perhaps it is the only way to end slavery. In 1857, his mother died, followed by Elizabeth in 1864. “And so,” she adds, “he loses a lot of his family support and then, after the war, sort of backs away from being the radical ‘out there’ abolitionist.”

He refocused on poetry, writing some of his best work in Amesbury. Snow-Bound sold 7,000 copies the first day and ultimately earned Whittier his first sense of financial security. It features characters, based on his family, who are sitting around a fire waiting out a winter storm by telling stories. They find comfort in each other and in domestic duties, even as the world outside transforms: “And, when the second morning shone,/We looked upon a world unknown,/On nothing we could call our own.” Whittier pays tribute to his own history and to the new promise of freedom, while acknowledging the traumas of war and encroaching industrialization. “It was for war-weary Americans who needed something quiet and beautiful to go back to,” Bryant notes. For Shaughnessy, the poem resonated with people remembering their own rural childhoods while watching New England landscapes give way to mills and factories—what amounted to “the loss of a way of life in America.”

It’s hard to grasp how important poetry and poets were to nineteenth-century readers. When Whittier died in 1892, some 5,000 people passed his coffin during the wake, and a thousand mourners packed into his Amesbury backyard for the funeral. Around the nation, streets, towns, and schools bear his name. Whittier, California, home to its eponymous college, honors him and his legacy, as does the John Greenleaf Whittier Bridge on Interstate 95 (which also features the William Lloyd Garrison pedestrian and bike trail) over the Merrimack River, linking Amesbury and Newburyport. And then there’s Mount Whittier in the Ossipee Mountain range in New Hampshire. “It’s a name that,” Shaughnessy adds, “once you start noticing it, is everywhere.”