In December 2023, David Carpenter was deep in the digital stacks of the Harvard Law School Library, sifting through unofficial copies of the Magna Carta for a book project, when he stumbled upon a document unassumingly titled “HLS MS 172.”

On the library’s website, the document was categorized as a Magna Carta copy from around 1327. Harvard had purchased it in 1946, from a London bookseller, for $27.50. But Carpenter, a professor of medieval history at King’s College London, was convinced it was something far more rare: an original 1300 Magna Carta, of which only six others are known to survive.

That would make it, he says, “one of the world’s most valuable documents.” (A 1297 version—thought at the time to be the only original Magna Carta in the United States—sold in 2007 for $21.3 million.)

“I thought—OMG, what is this?’” Carpenter recalls. He emailed the images to fellow Magna Carta scholar Nicholas Vincent, a professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia. “What do you think that is?” Vincent recalls him asking. He answered moments later: “You know jolly well what that is. It’s clearly an original. It’s not a copy.”

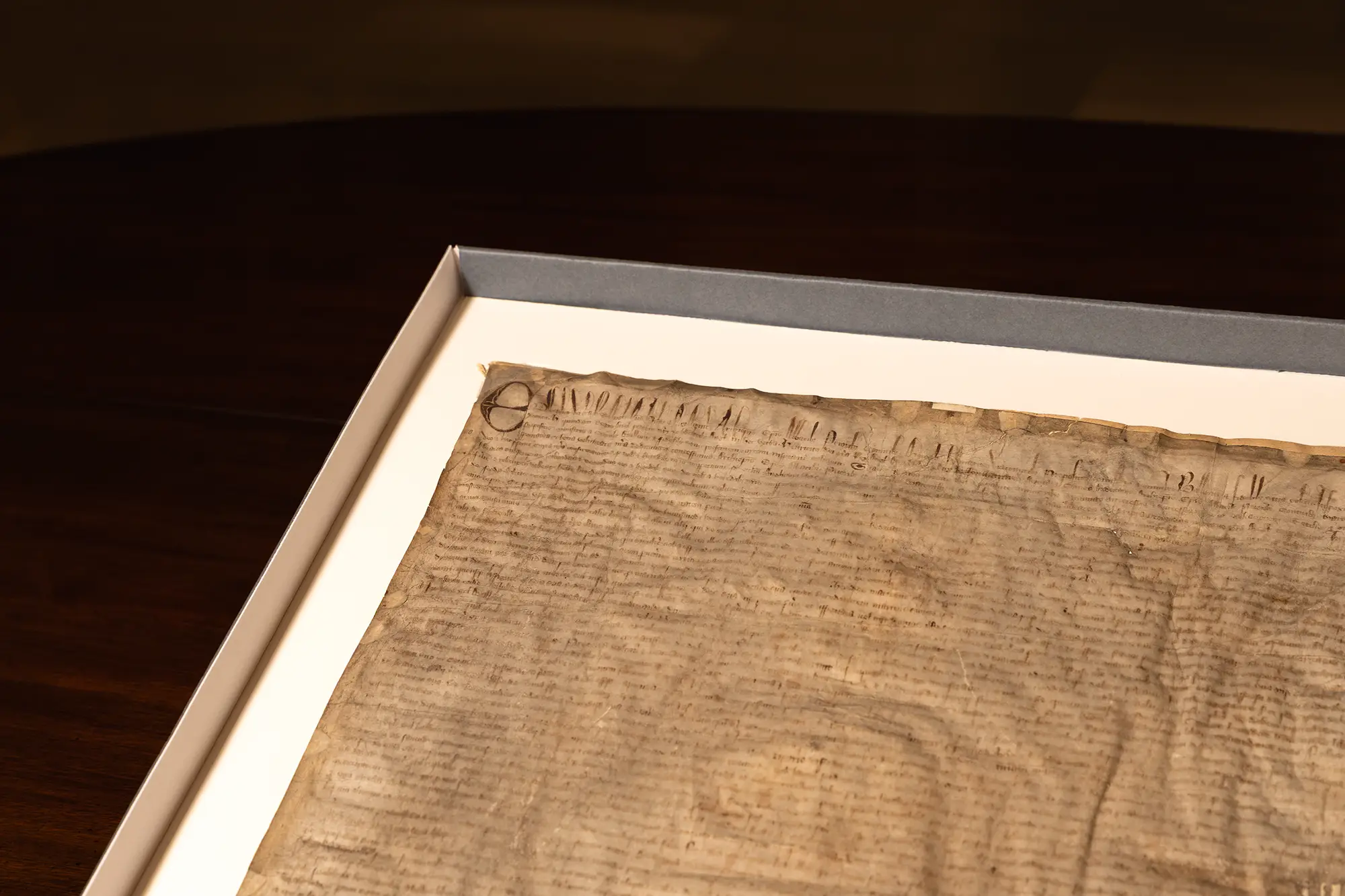

The two professors recognized several signs: the handwriting and size of the parchment—about 19-by-19 inches—were strikingly similar to those of the other official Magna Cartas from 1300. And most tellingly, the text stated that the document was issued in “the 28th year of Edward’s reign”—which dates it squarely to 1300.

In his excitement, Vincent immediately called the Harvard Law School Library to tell them what they possessed. They responded with “very lukewarm enthusiasm,” he recalls. “I think they may have thought that I was a lunatic, actually.” (Harvard librarians are used to people claiming to have made discoveries within their collections—some more significant than others.)

This time, though, the excitement was warranted: the library, working with the two scholars, has today confirmed the manuscript as the seventh known original of King Edward I’s 1300 Magna Carta confirmation. There are tentative plans to display the document during a Law School event with the professors in June. Beyond that, librarians are still determining the long-term plans for the manuscript, which is currently stored in a vault for fragile documents and artifacts.

The Magna Carta was first issued in 1215 as a check on the power of the English monarch. A group of rebellious barons forced King John to sign it, establishing fundamental rights such as due process and habeas corpus, a legal concept that guarantees freedom from illegal imprisonment. It later inspired foundational legal documents, including the United States Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Throughout the thirteenth century, subsequent kings reissued the Magna Carta several times—events known as “confirmations.” When King Edward I reissued the Magna Carta in 1300, clerks produced “well over 30” copies to distribute around the country, Carpenter says. Only six of those originals were thought to have survived, all of them in England.

The timing of the Harvard Law School discovery is “almost providential,” Vincent says. In addition to protecting individual rights, the Magna Carta “guarantees the liberties of corporations and institutions, like the Church, like the city of London, like the towns—or, you might say, like private universities,” Vincent says. “It guarantees them against arbitrary intervention by the state.”

“At a time when state authorities are doing strange things,” he continues, “it’s a very timely reminder that the rule of law governs the governors, as well as the governed.”

After Vincent contacted Harvard, the two scholars started a process to confirm their suspicions. Carpenter collated the six other known 1300 confirmations and found that this version was strikingly specific: clerks at the time had been instructed to meticulously replicate particular changes in diction and word order. This provided a test for HLS MS 127: if it was indeed a 1300 confirmation, its text would need to match the others.

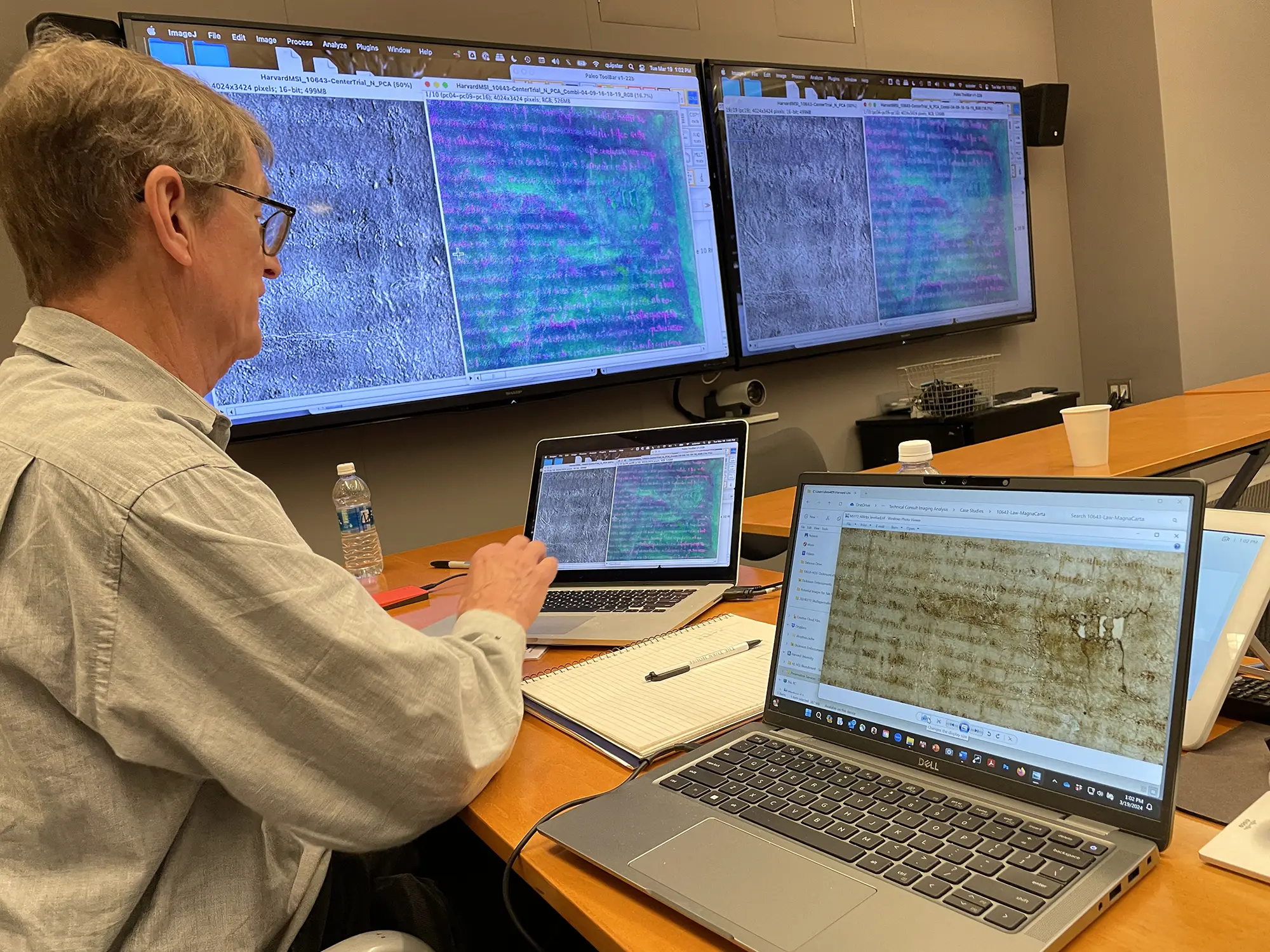

The text, however, was too faded to read clearly, so Harvard enlisted the company R.B. Toth Associates, which specializes in digital research technologies, to use ultraviolet light and spectral imaging to reveal the invisible writing. Once Carpenter received those images, he compared them to the confirmed authentic text.

“It was quite nerve-wracking,” he says, “but the merciful thing is, at the end, Harvard Law School passed the exam with flying colors.” The text matched exactly.

Meanwhile, Vincent set out to investigate the document’s provenance. He traced it back to an unlikely source: a World War I flying ace, Air Vice-Marshal Forster “Sammy” Maynard, CB. In 1945, Maynard sent the document to auction through Sotheby’s; it was then purchased by the London booksellers Sweet & Maxwell, who in turn sold it to the Harvard Law School Library in 1946, for what Carpenter calls “absolute peanuts.” The auction catalog described the manuscript as “a copy…made in 1327… somewhat rubbed and damp-stained.”

The question then became: “What on earth was a senior [Royal Air Force] officer doing with a Magna Carta?” as Vincent remembers asking. To find out, he contacted Maynard’s grandson, Peter Maynard, who revealed that his grandfather had inherited a trove of historical documents from Thomas and John Clarkson, leading campaigners against the British slave trade in the late eighteenth century.

That connection was the missing piece, Vincent says: Thomas Clarkson was closely acquainted with William Lowther, in effect the hereditary lord of the manor of Appleby. In 1300, a Magna Carta confirmation had been issued to the borough of Appleby; it was last seen there in 1762, before disappearing from the historical record. This, Vincent says, is likely the Magna Carta now held by the Law School Library.

There is more for contemporary students to learn from the Magna Carta than just its contents, Carpenter says. A legal document—whether the Magna Carta or the Constitution—is only as effective as its enforcement mechanism. The original 1215 Magna Carta had an explicit one: a council of 25 barons empowered to seize the king’s property if he violated the charter.

But that enforcement clause was removed from later versions. Throughout the thirteenth century, “people constantly said, ‘Look, the King may be breaking Magna Carta, but what can we do about it?’” Carpenter says.

Historically, what was the answer, in the absence of legal enforcement? “Public opinion,” Carpenter says. “If we take one of the most important principles of Magna Carta—which is that no tax could be levied without the consent of the kingdom—that was more or less obeyed all through the thirteenth century. And I think it was the feeling that if it’s not obeyed, there’s going to be a rebellion. There’s going to be trouble.”

“Ultimately,” he continues, “the strength of Magna Carta rests in the hearts and minds of people, and in what they might do if it’s broken, rather than any precise legal enforcement apparatus.” Through the centuries, the document’s principles have been safeguarded not only by judges and armies, but by the people.